|

CATTLE

323

CATTLE—(Continued.)

Cattle In Early History.............. 223

Continental and South American.....224

Escutcheon, the......................229

Europe, in :

Ayrshires........................... 226

Devons, the North................. 226

Habitat of Holsteins................ 227

Herefords, the..................... 225

Holsteinsat Home................. 228

Holstein Cattle....... ............ 227

Holsteins in Seventeenth Century.. 228

Jerseys, the........................ 226

Kyloes, the....................... 227

North Devons, the................. 226

Scotch Breeds...................... 226

Shetland Cattle.................... 227

Short-Horns, the................... 225

Suffolk Duns....................... 226

Welsh Cattle....................... 227

West Highland Cattle............. 227

Guenon, Fran90is................... 229

Humped Cattle..................... 223

In Mythology and Religion.......... 223

Less Common Uses.................. 224

Magne, Prof......................... 230

Milk-Mirror, the..................... 229

Mirror, the Milk-.................... 229

Naming of Cattle.................... 244

Once a medium of Exchange......... 223

“ Paster,” the........................ 243

Services, their....................... 223

Survivals............................ 224

Uncertainty of Records............. 243

United States, in the:

Angus, the Polled ................. 237

Ayrshires, Milk Record of......... 235

Ayrshires, the.............,........ 235’

Beef............................... 231

Campbell Sale, the................ 233

Census Returns.................. 231

Claims for Ayrshires............... 235

Comparative Value of Points...... 239

Comparisons...................... 242

Cow Echo..................... 231, 242

Cow Value 2d...................... 238

Dairy.............................. 231

Description of Jerseys.............. 238

Echo Farm....................... 237

Greatest Weekly Butter-Yield...... 238

Hereford Cow, the................. 233

Hereford Ox, the................... 233

Herefords for Beef................. 232

Herefords, the..................... 232

Holsteins, Milk sold............... 242

Holstein Points.................... 243

Holsteins, the...................... 240

United States, in the :—Cont'd.

Importation of Herefords.......... 23a

Introduction of Holsteins.......... 240

Jersey Cattle....................... 237

Jerseys Today.................... 238

Lady Seffinga...................... 240

Milk Records of Ayrshires......... 245

One Instance of Fattening......... 242

Oxen, Working.................... 231

Performance of Holsteins here..... 240

Points of Herefords................ 233

Points of Jerseys................... 238

Points of Holsteins................243

Polled Angus, the.................. 237

Polled Cattle....................... 236

Rationale of Short-Horns.......... 234

Sales of Polled Cattle.............. 237

Sale, the Campbell...............233

Sample Importation, a.............240

Short-Horns........................ 233

Short-Horns for Dairy............. 234

Short-Horns, Proper Home........ 234

Short-Horns, Rationale of......... 234

Status of Different Breeds........242

Value 2d........................... 238

Working Oxen..................... 231

Urus, the............................ 224

In Early History,—This is a term applied to the

various races of domesticated animals belonging

to the genus Bos. They have been divided into

two primary groups, the humped cattle, or zebus

(Bos indicus), of India and Africa, and the straight-

backed cattle ( Bos taurus), which are common

everywhere. By many naturalists these groups

have been regarded as mere races of the same

species, and it is a well-ascertained fact that the

offspring arising from the crossing of the humped

and unhumped cattle are completely fertile; but

the differences in their osteology, configuration,

voice and habits are such as to leave little doubt

of their specific distinctness. Oxen appear to

have been among the earliest of domesticated

animals, as they undoubtedly were among the

most important agents in the growth of early

civilization. They are mentioned in the oldest

Written records of the Hebrew and Hindu peo

ples, and are figured on Egyptian monuments

raised 2000 years before the Christian era; while

the remains of domesticated specimens have been

found in the Swiss lake-dwellings along with the

stone implements and other records of Neolithic

man.

Once a Medium of Exchange.—In infant commu

nities an individuals wealth was measured by the

number and size of his herds—Abram, it it said,

was rich in cattle ; and oxen for a long period

formed, as they still do among many Central

African tribes, the favorite medium of exchange

between nations. After the introduction of a

metal coinage into ancient Greece, the former

method of exchange was commemorated by

stamping the image of an ox on the new money;

while the same custom has left its mark on the

languages of Europe, as is seen in the Latin word

pecunia, and the English “pecuniary,” derived

from pecus, cattle.

In Mythology and Religion.—The value attached to

cattle in ancient times is further shown by the

Bull figuring among the signs of the zodiac; in

its worship by the ancient Egyptians under the

title of Apis ; in the veneration which has always

been paid to it by the Hindus, according to

whose sacred legends it was the first animal cre

ated by the three divinities who were directed by

the supreme Deity to furnish the earth with ani

mated beings ; and in the important part it was

made to play in Greek and Roman mythology.

The Hindus were not allowed to shed the blood

of the ox, and the Egyptians could only do so in

sacrificing to their gods. Both Hindus and Jews

were forbidden, in their sacred writings, to muzzle

it when treading out the corn ; and to destroy it

wantonly was considered a public crime among

the Romans, punishable with exile.

Humped Cattle are found in greatest perfection in

India, but they extend eastward to Japan, and

westward to the African Niger. They differ from

224 THE FRIEND OF ALL.

the European forms not only in the fleshy pro

tuberance in the shoulders, but in the number of

sacral vertebrae, in the character of their voice,

which has been described as “grunt-like,” and

also in their habits; “they seldom seek the

shade, and never go into the water and there

stand knee-deep like the cattle of Europe.” They

now exist only in the domesticated state, and ap

pear to have been brought under the dominion

of man at a very remote period, all the repre

sentations of the ox on such ancient sculptures

as those in the caves of Elephanta being ot the

humped or zebu form. There are several breeds

of the zebu, the finest occurring in the northern

provinces of India, where they are used for

riding,—carrying, it is said, a man at the rate of

six miles an hour for fifteen hours. White bulls

are held peculiarly sacred by the Hindus, and

when they have been dedicated to Siva, by the

branding upon them of his image, they are

thenceforth relieved from all labor. They go

without molestation wherever they choose, and

may be seen about Eastern bazars helping them

selves to whatever dainties they prefer at the

stalls of the faithful.

Less Common Uses.—The Hottentots and Kaffres

possess several valuable breeds, as the Namaqua

and Bechwana cattle, the latter with horns which

sometimes measure over thirteen feet from tip

to tip along the curvature. The cattle of those

semi - barbarous South - Africans appear to be

among the most intelligent of their kind,—cer

tain of them, known as backleys, having been

trained to watch the flocks, preventing them

from straying beyond fixed limits, and protecting

them from the attacks of wild beasts and from

robbers. They are also trained to fight, and are

said to rush into battle with the spirit of a war-

horse. Among the Swiss mountains there are

herds of cows, whose leaders are adorned with

bells, the ringing of which keeps the cattle to

gether, and guides the herdsman to their pasture-

grounds. The wearing of the bells has come to

be regarded as an honorable distinction by the

cows, and no punishment is felt so keenly as the

loss of them, the culprit giving expression to her

sense of degradation by the most piteous lowings.

Their Services.—It is impossible to over-estimate

their services to the human race. Living, the

ox—taking that name as the representative of

Bos—plows its owner's land, and reaps his har

vest, carries his goods or himself, guards his

property, even fights his battles, while its udder,

which under domestication has been enormously

enlarged, yields him at all seasons a copious sup

ply of milk, butter and cheese. When dead, its

flesh forms a chief class of animal food ; its bones

are ground into manure or turned into numerous

articles of use or ornament; its skin is made into

leather, its ears and hoofs into glue; its hair is

mixed with mortar; and its horns are cut and

molded into various articles of use.

The Urus.—The most important ancestor of our

present domestic cattle, in Europe and America,

was the Urus (Bos primigenius). Cæsar describes

it as existing in his time, in the Hercynian Fo

rest, in size almost as large as an elephant, but

with the form and color of a bull; and it is men

tioned by Heberstein so late as the 16th century

as still a favorite beast of chase. The Urus was

characterized by its flat or slightly concave fore

head, its straight occipital ridge, and the pecu

liar curvature of its horns. Its immense size

may be gathered from the fact that a skull in the

British Museum, found near Atholl, in Perth

shire, measures one yard in length, while the

span of the horn-cores is three feet six inches.

Survivals.—British wild cattle now exist only in

a few parks, where they are strictly preserved.

The purest bred are those of Chillingham, a

park in Northumberland, belonging to the Earl

of Tankerville, and which was in existence in the

13th century. These have red ears with brown

ish muzzle, and show all the characteristics of

wild animals. They hide their young, feed in

the night, basking or sleeping during the day;

they are fierce when pressed, but, generally speak

ing, very timorous, moving off on the appearance

of any one even at a great distance. The bulls

engage in fierce contests for the leadership of

the herd, and the wounded are set upon by the

others and killed ; thus few bulls attain a great

age, and even those, when they grow feeble, are

gored to death by their fellows. The white cat

tle of Cadzow Forest are very similar in their

habits to those of Chillingham, but being con

fined to a narrow area are less wild. They still

form a considerable herd, but of late years, it has

been stated, they have all become polled, or horn

less. Sir Walter Scott maintained that Cadzow

and Chillingham are but the extremities of what

in earlier times was a continuous forest, and that

the white cattle are but the remnants of those

herds of “tauri sylvestres” described by early

Scottish writers as abounding in the forests of

Caledonia, and to which he evidently refers in

these lines:

“ Mightiest of all the beasts of chase

That roam in woody Caledon,

Crashing the forest in his race,

The mountain bull comes thundering on.”

Continental and South American Cattle.—Of these

the Hungarian is conspicuous from its great size,

and the extent of its horns, which often measure

five feet from tip to tip. The cattle of Friesland,

Jutland and Holstein form another large breed,

and these, it is said, were introduced by the

CATTLE. 225

Goths into Spain, thus becoming the progenitors

of the enormous herds of wild cattle which now

roam over the Pampas of South America. Co

lumbus in 1493 brought to America a bull and

several cows. Others were brought by succeed

ing Spanish settlers. They are now widely

spread over the plains of South America, but

are most numerous in the temperate districts of

Paraguay and La Plata—a fact which bears out

the view taken by Darwin, that our oxen are the

descendants of species originally inhabiting a

temperate climate. Except in greater uniformity

of color, which is dark-reddish brown, the Pam

pas cattle have deviated but little from the an

cestral Andalusian type. They roam in great

herds in search of pasture, under the leadership

of the strongest bulls, and avoid man, who hunts

them chiefly for the value of their hides, of which

enormous quantities are exported annually from

Buenos Ayres. They are, however, readily re

claimed ; the wildest herds, according to Prof.

Low, being often domesticated in a month.

These cattle have hitherto been chiefly valued

for their hides, and as supplying animal food to

the inhabitants, who use only the choicest parts ;

but lately attempts have been made, and with

considerable success, to export the beef in a pre

served state. Although the South American

cattle have sprung from a single European breed,

they have already given rise to many well marked

varieties, as the polled cattle of Paraguay, the

hairless breed of Colombia, and that most mon

strous of existing breeds, the Natas, two herds

of which Darwin saw on the banks of the Plata,

and which he describes as “bearing the same

relation to other cattle as bull or pug dogs do to

other dogs.” Cattle have been introduced by

the colonists into Australia and New Zealand,

where they are now found in immense herds,

leading a semi-wild existence on the extensive

“ runs” of the settlers.

BREEDS IN GREAT BRITAIN.

Taking up the most important of these breeds,

and without entering into curious speculation on

their origin, we will notice them in what seems a

natural order. The first place belongs to

The Short-Morns.—It appears that from an early

date the valley of the Tees possessed a breed of

cattle which, in appearance and general qualities,

were probably not unlike the quasi shorthorns

which are now so plenty. A Mr. Waistell of

Allihill admired a certain bull, Hubback, but

hesitated to buy him at the high price of 8l. He

joined with a Mr. Colling in the purchase. After

wards they sold to another Colling, who confined

the bull to his own stock, refusing his use to

even one of Mr. Waistell's cows. The Collings

entered on their work of improvement at a very

15

favorable time, and with promising materials

ready to their hands. But these materials seemed

with them at once to acquire an unwonted plas

ticity ; for in a very short time their cattle ex

hibited, in a degree that has hardly yet been

excelled, that combination of rapid and large

growth with aptness to fatten, of which their

symmetry, good temper, mellow handling and

gay colors are such pleasing indices and accom

paniments, and for which they have acquired a

worldwide celebrity. These Durham, Tees-

water or Short-Horn cattle, as they were variously

called, were soon eagerly sought after, and

spread with amazing rapidity. For a time their

merits were disputed by the eager advocates of

other and older breeds, some of which they have

utterly supplanted, while others, such as the

Herefords, Devons and Scotch polled cattle,

have each their zealous admirers, who still main

tain their superiority to the younger race.

But this controversy is getting practically de

cided in favor of the Short-Horns, which con

stantly encroach upon their rivals, even in their

headquarters, and seldom lose ground which

they once gain. Paradoxical as the statement

appears, it is yet true that the very excellence of

the Short-Horns has in many cases led to their

discredit. Many persons desiring to possess

them, and yet grudging the cost of purebred

bulls, have used worthless cross-bred males, and

so have filled the country with an inferior race

of cattle, bearing indeed a general resemblance

in color, and partaking in some measure of the

good qualities of Short-Horns, but utterly want

ing in their peculiar excellences. By ignorant

or prejudiced persons the genuine race is never

theless held answerable for the defects of the

mongrels which usurp their name, and for the

damaging comparisons which are made between

them and choice specimens of other breeds.

That the Short-Horn should spread as it does,

in spite of this hinderance, is no small proof of

its inherent excellence, and warrants the infe

rence that it will take its place as the one appro

priate breed of the fertile and sheltered parts of

Great Britain.

The Hereford is the breed which in England

contests most closely with the Short-Horns the

palm of excellence. They are admirable grazier‘s

cattle, and when of mature age and fully fattened

present exceedingly level, compact and massive

carcasses of excellent beef. But the cows are

poor milkers, and the oxen require to be at

least two years old before being put up to fatten

—defects fatal to the claims put forward in their

behalf. To the grazier who purchases them

when their growth is somewhat matured they

usually yield a good profit, and will generally

excel Short-Horns of the same age. But the

226

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

distinguishing characteristic of the latter is that,

when properly treated, they get sufficiently fat

and attain to remunerative weights at, or even

under, two years old. If they are kept lean

until they have reached that age, their peculiar

excellence is lost. From the largeness of their

frame they then cost more money, consume

more food, and yet do not fatten more rapidly

than bullocks of slower growing and more com

pactly formed breeds. It is thus the grazier fre

quently gives his verdict in favor of Herefords as

compared with Short-Horns. Even under this

mode of management Short-Horns will usually

yield at least as good a return as their rivals to

the breeder and grazier conjointly. But if fully

fed from their birth so as to bring into play their

peculiar property of growing and fattening simul

taneously, they will yield a quicker and better

return for the food consumed by them than

cattle of any other breed. These remarks apply

equally to another breed closely allied to the

Herefords, viz.,

The North Devons, so much admired for their

pleasing color, sprightly gait and gentle temper,

qualities which fit them beyond all other cattle

for the labor of the field. If it could be proved

that ox-power is really more economical than

horsepower for any stated part of the work of

the farm, then the Devons, which form such ad

mirable draught-oxen, would be deserving of

general cultivation. It is found, however, that

when agriculture reaches a certain stage of pro

gress, ox-labor is inadequate to the more rapid

and varied operations that are called for, and has

to be superseded by that of horses.

Scotch Breeds.—These indigenous breeds of

heavy cattle are for the most part black and

hornless. Prominent among them are the Aber

deen, the Angus and the Galloway. These are

all valuable breeds, being characterized by good

milking and grazing qualities, and by a hardiness

which peculiarly adapts them to a bleak climate.

Cattle of these breeds, when they have attained

to three years old, fatten very rapidly, acquire

great size and weight of carcass, and yield beef

unsurpassed in quality.

The cows of these breeds, when coupled with

a Short-Horn bull, produce an admirable cross-

breed, which combines largely the good qualities

of both parents. The great saving of time and

food which is effected by the earlier maturity of

the cross-breed has induced a very extensive

adoption of this practice in all the north-eastern

counties of Scotland. Such a system is neces

sarily inimical to the improvement of the pure

native breeds; but when cows of the cross-breed

are continuously coupled with pure Short-Horn

bulls, the progeny in a few generations becomes

assimilated to the male parent, and are charac

terized by a peculiar vigor of constitution and

excellent milking yield in the cows. With such

native breeds to work upon, and this aptitude to

blend thoroughly with the Short-Horn breed, it

is much more profitable to introduce the latter in

this gradual way of continuous crossing than at

once to substitute the one pure breed for the

other. The cost of the former plan is much

less, as there needs but the purchase from time

to time of a good bull, and the risk is incom

parably less, as the stock is acclimatized from

the first, and there is no danger from a wrong

selection. The greater risk of miscarriage in

this mode of changing the breed is from the

temptation to which, from mistaken economy,

the breeder is exposed of rearing a cross-bred

bull himself, or purchasing a merely nominal

Short-Horn bull from others.

The Ayrshires stand in the front rank in Great

Britain, as profitable dairy cattle. From the

pains which have been taken to develop their

milk-yielding power, it is now of the highest

order. Persons conversant only with grazing

cattle cannot but be surprised at the strange

contrast between an Ayrshire cow in full milk

and the forms of cattle which they have been

used to regard as most perfect. Her wide pelvis,

deep flank and enormous udder, with its small

wide-set teats, seem out of all proportion to her

fine bone and slender fore-quarters. The breed

possess little merit for grazing purposes. Useful

results are obtained by crossing these cows with

a Short-Horn bull, and this practice is gaining

ground. But the function of the Ayrshire cattle

is the dairy. For this they are unsurpassed,

either as respects the amount of produce yielded

by them in proportion to the food which they

consume, or the faculty which they possess of

converting the herbage of poor exposed soils,

such as abound in their native district, into

butter and cheese of the best quality.

The Suffolk Duns.—These are a polled breed of

cattle, the prevailing color of which is dun or

pale red, for whose dairy produce the county of

Suffolk has long been celebrated. They have a

strong general resemblance to the Scotch polled

cattle, but nevertheless seem indigenous to Suf

folk. They are ungainly in their form and of

little repute with the grazier, but possess an un

doubted capacity of yielding a large quantity of

milk in proportion to the food which they con

sume. They are now encroached upon by, and will

probably give place to, the Short Horns, by which

they are decidedly excelled for the combined

purposes of the dairy and the fattening-stall.

The Jerseys.—Four little islands lie off the

north-west coast of France near Cherbourg,

called the Channel Islands, belonging to Great

Britain, the only parts of Normandy she has left.

CATTLE.

227

These islands are four, Jersey, Guernsey, Alder-

ney and Sark, the last a very small one, and the

whole group has an area of only 73 square miles,

and a population in 1871 of a little more than

90,000. Yet from this little group come the

names Jersey, Alderney and Guernsey, names as

familiar as household words in cattle and dairy

matters. These cattle are so remarkable for the

choice quality of the cream and butter obtained

from their rather scanty yield of milk, that they

are eagerly sought after for private dairies, in

which quality of produce is more regarded than

quantity. The rearing of heifers for the English

market is of such importance to these islands

that very stringent regulations have been

adopted for insuring the purity of their peculiar

breed. These cattle in general are utterly worth

less for the purposes of the grazier. The choicer

specimens of the Jersey have a certain deer-like

form which gives them a pleasing aspect. In

fact, in their native island there is a tradition

that ascribes their progenitors to some mysteri

ous cross with a deer, and their large, round,

lustrous eyes lend credence to the conjecture.

The race, as a whole, bear striking resemblance

to the Ayrshires, which are alleged to owe their

peculiar excellences to an early admixture of

Jersey blood.

The Jersey cattle will claim large attention

under Cattle in the United States.

The Kyloes, or West Highland cattle, are a moun

tain breed, widely diffused over the Highlands of

Scotland, but are found in the greatest perfection

in the larger Hebrides. Well-bred oxen of this

breed, when of mature growth and in good con

dition, exhibit a symmetry of form and noble

bearing unequaled among British cattle. Al

though somewhat slow in arriving at maturity,

they are contented with the coarsest fare, and

ultimately get fat where the daintier Short-

Horns could barely exist. Their hardy constitu

tion, thick mellow hide, and shaggy coat, pecu

liarly adapt them for a cold humid climate and

coarse pasturage. The milk of these cows is

very rich, but as they yield it in small quantity,

and soon go dry, they are unsuited for the dairy,

and are kept almost solely for the purpose of

suckling each her own calf. The calves are

generally housed during the first winter, but

after that they shift for themselves out of doors

the whole year round. Vast droves of these

cattle are annually transferred to the lowlands,

where they are in request for their serviceable-

ness in consuming profitably the produce of

coarse pastures and the leavings of daintier

stock. When of a dun or tawny color, they have a

picturesque look grazing in a park with deer.

There is a strong family likeness between them

and the

Welsh Cattle, which is what might be expected

from the many features, physical and historical,

which the two provinces have in common. Al

though the cattle of Wales are obviously, as a

whole, of common origin, they are yet ranged

into several groups, which owe their distinctive

features either to peculiarities of soil and

climate or to intermixture with other breeds.

The Pembrokes may be taken as the type of the

mountain groups. These are hardy cattle, which

thrive on scanty pasturage and in a humid cli

mate. They excel the West Highlanders in this

respect, that they make good dairy cattle, the

cows being peculiarly adapted for a small farmer's

purposes. When fattened they yield beef of ex

cellent quality. Their prevailing and most es

teemed color is black, with deep orange on the

naked parts. The Anglesea cattle are larger and

coarser than the Pembrokes, and those of Merio

neth and the higher districts are smaller and

inferior to them in every respect. The county

of Glamorgan possesses a peculiar breed, bearing

its name, which has long been in estimation for

combined grazing and dairy purposes. It has

latterly been so much encroached upon by Here-

fords and Short Horns that there seems some

likelihood of its becoming extinct, which will be

cause for regret unless pains are taken to occupy

its place with cattle not inferior to it in dairy

qualities.

The Shetland Cattle are the most diminutive in

the world. The carcass of a Shetland cow, when

fully fattened, scarcely exceeds in weight that of

a long-wooled wether. These little creatures

are, however, excellent milkers in proportion to

their size; they are very hardy, are contented

with the scantiest pasturage, come early to ma

turity, are easily fattened, and their beef surpasses

that of all other breeds for tenderness and deli

cacy of flavor. The diminutive cows of this

breed are not unfrequently coupled with Short-

Horn bulls, and the progeny from such apparently

preposterous unions not only possess admirable

fattening qualities,but approximate in bulk to their

sires. These curious and handsome little creatures,

apparently of Scandinavian origin, are so peculi

arly fitted to the circumstances of their bleak and

stormy habitat, that the utmost pains ought to

be taken to preserve the breed in purity, and to

improve it by judicious treatment.

HOLSTEIN CATTLE.

Their Habitat.—John Weiss tells of “the way in

which the Dutch people were prepared to main

tain liberty of thought and worship. A poor

Frisian race was selected, and kept for centuries

up to its knees in the marshes through which

the Rhine emptied and lost itself. Here it lived

in continual conflict with the Northern Ocean.

228

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

forced literally to hold the tide at arm's length, I

while a few acres of dry land might yield a scanty

subsistence.” From the land thus rescued from

the German Ocean, come the cattle known as

Dutch, Dutch-Frisian, and Holstein, the latter

name being perhaps that most generally em

ployed. The Holstein Herd-Book affirms that

“the present large improved black-and-white

cattle of North Holland, Friesland and Olden

burg, which all possess the same general charac

teristics, yet present in the different localities

some slight dissimilarity, and have perhaps been

brought to the highest degree of perfection in

the first-named province, undoubtedly descended

from the original stock of Holstein.”

In the Seventeenth Century.—In this century, as

represented by Motley in his History of the

United Netherlands, the cattle interest in Hol

land had become of prime importance to the

people, and was in the most thrifty condition. He

says : “ On that scrap of solid ground, rescued

by human energy from the ocean, were the most

fertile pastures in the world. An ox often weighed

more than two thousand pounds. The cows pro

duced two or three calves at a time, and the

sheep four or five lambs. In a single village, four

thousand kine were counted. Butter and cheese

were exported to the annual value of a million ;

salted provisions to an incredible extent. The

farmers were industrious, thriving and indepen

dent. It is an amusing illustration of the agri

cultural thrift and republican simplicity of this

people that on one occasion a farmer proposed

to Prince Maurice that he should marry his

daughter, promising with her a dowry of a hun

dred thousand florins.” And one can well ima

gine that the farmer's daughter, when the august

head of John of Barneveldt rolled from the heads

man's axe, rejoiced that her blood had not been

mingled with that of Maurice : in this and other

transactions anything but a Prince.

In the Nineteenth Century, and at Home.—Prof.

Roberts, before the New York Dairyman's Asso

ciation, says: “ I had the good fortune, during

the past summer, to spend some time in North

Holland and Friesland, a country usually ignored

by the tourist, though full of instructive sights

and quaint old customs. Here in ancient grass-

bottomed lakes, snatched from the inroads of

the sea, by the greatest skill and labor the world

has ever known, I found the ideal milk-producer.

Situated in a level, rich, moist country well

adapted to the production of forage-grasses,

with a climate cool but equable in summer, but

raw, windy and cold in winter; here, favored yet

unfavored by nature, these clean, plain, intelligent

Dutch have reduced to a science the economical

production of milk. Of course this could not be

done without a good cow; and if anywhere on \

the face of the globe there exists a race of uniformly

good milkers, the Dutch have them. I care not

what a man's prejudices be, whether an admirer

of the fawn-eyed Jersey, or (like myself) of that

grand old breed the Short-Horn, the stately Here

ford or the piebald Ayrshire, if he really admire

a good cow, he cannot help falling in love with

the picturesque Holstein, as seen in its native

pastures in the north countries. He may return

to his American home and conclude that his cir

cumstances are better adapted to some other

breed, but he will ever after speak of them only

with praise.

“ I have said they were a race of good milkers;

and I think I have not put it too strong when I

say truthfully, that neither from Beemster Polder

northward, nor in Friesland, did I see what

might be called a poor cow or an old cow,

though I saw many hundreds.

“ Here is a people, occupying lands which are

seldom sold for less than five hundred dollars per

acre, more frequently for a thousand, and up

wards, producing butter and cheese, and placing

it on the European market in successful compe

tition with that produced on lands of less than a

tenth of their value. With these facts staring us

in the face it looks quite possible that we might

learn something of more economical production,

from these miscalled dumb Dutch, notwithstand

ing they still cut their grass by hand, have no

tongues or thills to their farm-wagons, and wear

wooden shoes. Without a herd-book, till quite

recently, and without any great leaders or im

provers in cattle-breeding as found in Bakewell,

Colling, Bates and Booth of England, these quiet

people have, by common sense and universal

methods, long since formed a distinct breed of

cattle that surpasses, in their locality, all others

so far as tried. Jerseys have been introduced, but

cannot secure a footing. Here and there at long

intervals we find an effort has been made to im

prove by a cross of the English bull, but, so far

as I could learn, deterioration in milking qualities

has resulted with but slight compensating im

provement in beef qualities. The details of the

ancient breeding and management of the Hol-

steins have not been handed down to us, as that

of the Short-Horns; but from the location and

habits of the people we may fairly infer that they

differed but slightly if at all from those of modern

times. Having unusually fine facilities, I tried

to study carefully their present methods, and also

their results.

“ In the first place, but few bulls are kept, and

these but for two or three years at most, when

they are sold in the market for beef. These

bulls are selected with the utmost care, invariably

being the calves of the choicest milkers. But

little attention is paid to fancy points or colon

CATTLE. 229

though dark spotted is preferred to light spotted,

though more attention is now being paid to

color in order to suit American customers. All

other bull-calves with scarce an exception are

sold as veals, bringing about one and a half times

as much as with us. In like manner the heifer

calves are sold except about twenty per cent,

which are also selected with care and raised on

skimmed milk. The age of the cow is usually

denoted by the number of her calves, and in no

case did I find a cow that had had more than six

calves, usually only four or five. Their rule is to

breed so that the cow‘s first calf is dropped in the

stable before the dam is two years old, in order

that extra care and attention may be given.

There are other objects gained by this method;

for should the heifer fall below their high stan

dard she goes to the butcher before another win

tering, and though she brought little profit to the

dairy she will more than pay for her keeping, at

the block.

“ Here we find a threefold method of selection.

First, in the sire; second, in the young calf,

judged largely by the milking qualities of the

dam ; and lastly is applied the greatest of all

tests, performance at the pail; and not till she

answers this satisfactorily is she accorded a per

manent place in the dairy.

“ The cows, no matter how good, are seldom

kept till they become ‘ old worn-out shells,’ val

ueless for beef, and not fit to propagate their

kind, but are sold for beef while they are vigorous

enough to put on flesh, profitable alike to pro

ducer and consumer, and of no mean quality. I

ate it for three weeks, and the English beef for

two, and while not so fat as the Short-Horn, it

was to my taste superior.

“ My experience is not extended enough to

justify me in saying that they are the best breed

for us, all things considered, but I believe them

to be.”

Requirements at Home.—“ The principles on which

they practice, in selecting a cow to breed from,

are as follows: She should have considerable

size, not less than four and a half or five feet

girth, with a length of body corresponding; legs

proportionately short; a finely formed head, with

a forehead or face somewhat concave; clear,

large, mild and sparkling eyes, yet with no ex

pression of wildness; tolerably large and stout

ears, standing out from the head; fine, well-

curved horns; a rather short than long, thick,

broad neck, well set against the chest and with

ers ; the front part of the chest and the shoulders

must be broad and fleshy; the low-hanging dew

lap must be soft to the touch ; the back and loins

must be properly projected, somewhat broad, the

bones not too sharp, but well covered with flesh;

the animal should have long curved ribs, which

form a broad breastbone; the body must be

round and deep, but not sunken into a hanging

belly; the rump must not be uneven ; the hip-

bones should not stand out too broad and spread

ing, but all the parts should be level and well

filled up; a fine tail, set moderately high up, and

tolerably long but slender, with a thick, bushy

tuft of hair at the end, hanging down below the

hocks; the legs must be short and low, but strong

in the bony structure; the knees broad, with flexi

ble joints; the muscles and sinews must be firm

and sound ; the hoof broad and flat, and the

position of the legs natural, not too close and

crowded; the hide, covered with fine, glossy hair,

must be soft and mellow to the touch, and set

loose upon the body. A large, rather long, white

and loose udder, extending well back, with four

long teats, serves, also, as a characteristic mark

of a good milch-cow. Large and prominent milk-

veins must extend from the navel back to the

udder; the belly of a good milch-cow should not

be too deep and hanging.”

THE ESCUTCHEON, OR MILK-MIRROR.

Francois Guenon, a native of Libourne, France,

who became a cattle-dealer in 1822, discovered

and perfected a system for learning the value of

a cow as a milker, by observing her escutcheon,

or milk-mirror, as it is often called, extending, in

the best animals, from the root of the tail, down

over the udder and behind the thighs. In 1837

the Agricultural Society of Bordeaux appointed

a committee to investigate the worth of this sys

tem. That committee reported :

“ Every cow subjected to examination was sepa

rated from the rest. What M. Guenon had to say

in regard to her was taken down in writing by

one of the committee ; and immediately after, the

proprietor, who had kept at a distance, was inter

rogated, and such questions put to him as would

tend to confirm or disprove the judgment pro

nounced by M. Guenon. In this way we have

examined in the most careful manner—note being

taken of every fact and every observation made by

any one present—upwards of sixty cows and hei

fers ; and we are bound to declare that every state

ment made by M. Guenon, with respect to each of

them, whether it regarded the quantity of milk,

or the time during which the cow continued to

give milk after being got with calf, or, finally, the

quality of the milk as being more or less creamy

or serous, was confirmed, and its accuracy fully

established. The only discrepancies which oc

curred were some slight differences in regard to

quantity of milk ; but these, as we afterwards

fully satisfied ourselves, were caused entirely by

the food of the animal being more or less

abundant.”

Their conclusion is now substantially accepted.

230

THE FRIEND OF ALL.

The system must be applied “with brains, sir;”

and so applied it has come to be of the greatest

value to the seeker for milk.

Guenon claimed for his system that it deter

mined :

1. The quantity of milk which a cow would

yield.

2. The period which she would continue in

milk.

3. The quality of her milk.

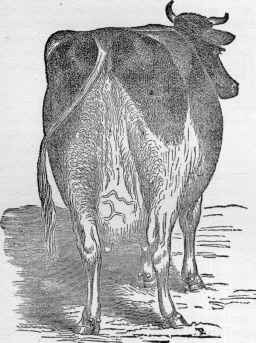

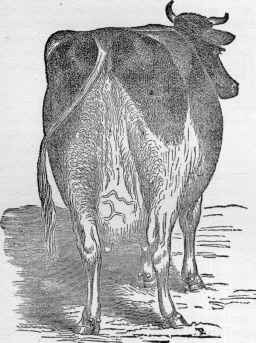

His description of the escutcheon is : “ This

mark consists of the figure, on the posterior parts

of the animal, formed by the meeting of the hair

that grows or points in different directions, the

line of junction of these different growths of hair

Escutcheon of Lady Mid would, imported from North

Holland, by Winthrop W. Chenery.

constituting the outline of the figure, or escutch

eon. His system exhibits 27 different diagrams

of varying grades of milking qualities, each grade

with what he calls a “bastard “ escutcheon. He

uses this word “to denote those cows which give

milk only so long as they have not been got in

with calf anew, and which, upon this happening,

go dry all of a sudden or in the course of a few

days. Cows of this kind are found in each of the

classes, and in every order of the class. Some of

them are great milkers, but, so soon as they have

got with calf, their milk is gone. Others present

the most promising appearance, but their yield is

very insignificant.”

The hair indicating a good milker turns up

ward, is short and fine, and presents peculiar oval

marks, or scurf-spots. The skin over this whole

surface is easily raised, and is especially soft and

fine in good milkers. Guenon‘s theory is that

the more that upward growth of hair extends

outward from the udder and inner parts of the

thighs, and upward towards the urinary passage

from the bladder, the better milker the cow is;.

and as the hair fails to extend upward and out

ward, in these directions, the less is she a good

milker.

The rationale of the system, according to an

other French authority, Prof. Magne, of Alfort, is:

“ The relations existing between the direction

of the hair of the perinæum, and the activity of

the milky glands, cannot be disputed. Large

lower tufts are marks of good cows, whereas tufts

near the vulva are observed on cows which dry

up shortly after they are again in calf.

“But what is the cause of these relations?

What connection can there be between the hair

of the perinæum and the functions of the milky

glands? The direction of the hair is subordinate

to that of the arteries; when a large plate of hair

is directed from below, upward, on the posterior

face of the udder, and on the twist, it proves that

the arteries which supply the milky system are

large, since they pass backwards beyond it, con

vey much blood, and consequently give activity

to its functions. Upper tufts, placed on the sides

of the vulva, prove that the arteries of the genera

tive organs are strongly developed, reach even to

the skin, and give great activity to those organs.

The consequence is, that after a cow is again in

calf, they draw off the blood which was flowing

to the milky glands, lessen, and even stop the

secretion of milk.

“In the bull, the arteries, corresponding to the

mammary arteries of the cow, being intended

only for coverings of the testicles, are very

slightly developed ; and there, accordingly, the

escutcheons are of small extent.”

While many dispute the value of the system in

its entirety, and even adduce instances in which

the facts seem diametrically opposed to the

theory of M. Guenon, the general verdict is, that,

like phrenology, there is a great deal in it, and

that the escutcheons of both cows and bulls pre

sent evidence which no intelligent farmer or

breeder can afford to disregard. The investiga

tion has been from the start a fascinating one;

and any reader who will go into it, studying the

system in all the lights he can have access to, and

trying it by all the facts within his reach, will

find that the interest will not diminish as he

goes on.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

|

|

VET INDEX

|

|

ANIMAL INDEX - OLD VET TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES.

|

|

FARMING INDEX - OLD FARM PRACTICES AND REMEDIES FOR ANIMALS, PLANTS AND FIXING THINGS.

|

Copyright

© 2000-2009 Donald Urquhart.

All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property

of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance

of our legal

disclaimer. |

|