| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

LEPRA2

Synonyms.—Leprosy; Lepra Arabum; Elephantiasis Græcorum; Leontiasis;

Satyriasis; Fr., La lèpre; Ger., Der Aussatz; Norwegian, Spedalskhed.

Definition.—Lepra is an endemic, chronic, malignant, constitu

tional disease, due to a specific bacillus, characterized by alterations in

the cutaneous, nerve, and bone structures, varying in its morbid mani

festations according to whether the skin, nerves, or other tissues are

predominantly involved, and resulting in anesthesia, ulceration, necrosis,

general atrophy, and deformity.

Ill-defined records of the existence of this malady are to be found

as far back as the remotest ages. Although its primary origin is unknown

it is not improbable, that it was in its earliest history limited to Egypt

and the Orient. Mention, sometimes of an indefinite character, is made

of it in several parts of the earlier books of the Bible.3 During the middle

ages it was quite rife in Europe, England, and Scotland, declining in the

fifteenth century and practically disappearing by the sixteenth. In

the last hundred years there seems to have been, in certain places, signs

of recrudescence, and the malady has appeared in parts where it had

1A review of the literature of x-ray in the leukemias, with bibliography, will be

found in a paper by Pancoast, in Univ. Pa. Med. Bull., Jan., 1907; and Stengel and

Pancoast, “The Treatment of Leukaemia and Pseudoleukæmia with X-rays,” Jour.

Amer. Med. Assoc, Sept., 28, 1912, p. 1166—in former over long bones, in latter over

glandular enlargements.

2 Important general literature: Danielssen and Boeck, Traite de la Spedalskhed,

Paris, 1848; Vandyke Carter, “Leprosy and Elephantiasis,” 1874; Leloir, “Traité

pratique et théorique de la Lèpre,” Paris, 1886; Thin, “Leprosy,” London, 1891;

Journal of the Leprosy Investigating Committee, London, 1890-91; Hansen and Looft,

“Die Lepra vom klinischen und pathologischen-anatomischen Standpunkt,” Bibli-

otheca medica, D. 2, H. 2; there is an English translation by Walker, London, 1895;

Mittheilungen und Verhandlungen der Internat. Lepra Conferenz zu Berlin, 1897, Berlin,

1897-98; Lepra-Bibliotheca international; Babes, “Die Lepra,” 1901; Santon, “La

Léprose,” 1901; Verhandl. v. Inlernat. Derm. Cong., Berlin, 1904, vol. i. The transac

tions of the International Congresses on Leprosy; Lie, Archiv, 1911, cx, p. 473 (sta

tistical review, based on over 1000 cases). Other literature will be referred to in the

course of the text.

3 McEwen, in two interesting papers, “The Leprosy of the Bible in its Medical

Aspect,” The Biblical World, No. 3, Sept., 1911, and “The Leprosy of the Bible: its

Religious Aspect,” ibid., No. 5, 1911, very properly concludes that leprosy of the Bible,

as also believed by most men competent to study the subject, includes many cutaneous

affections:—“The word ‘leprosy’ did not refer ever and always to true leprosy, but

was rather a generic term covering various sorts of inflammatory skin diseases, which

rendered the one afflicted unfit to associate with others, not because his condition was

contagious as a disease, but because, by virtue of the belief among the Hebrews in the

principle today known as ‘taboo,’ it disqualified him for the worship of Jehovah,

threatened others by contact with a like disqualification, and required ceremonial

procedure for removal. When this simple, and, we believe, true explanation of biblical

leprosy is understood and accepted, a great step will be taken toward the elimination of

the irrational lepraphobia of today.”

Any one who has carefully studied the subject cannot think otherwise. More

over, I am convinced that the history of the so-called great spread of the disease in

middle Europe, England, and Scotland during the middle ages and in a century or two

gradually disappearing is similarly largely mythical, due to a hysteric wave of lep-

raphobia and ignorance in diagnosis, which resulted in placing most skin disease cases,

among which doubtless some true leprosy cases, under this ban—to remain until fear

had ceased and knowledge had increased.

LEPRA

915

never before existed. It is probable, however, that this alleged increase

or recrudescence is more apparent than real, the studies and activity of

dermatologic workers in the past several decades in regard to the disease

bringing the existent cases and facts more strongly into the foreground.

Its distribution is, however, quite extensive, although the aggregated

number of cases, as well as the percentage of state and world population,

is insignificant compared to that during the early and middle ages. It

still exists today to a variable extent in Norway and Sweden, Southern

Russia, Asia, Japan, along the coasts of Africa, some of the Central and

South American States, Mexico, Cuba, and the Sandwich Islands. It

is also found in some of the British Colonies,1 in many of the islands of the

Indian and Pacific Oceans, New Zealand, Madeira, and the West

Indies. Spain and Portugal, as well as Greece and certain parts of

Italy and France, furnish a variable number of cases.

In the United States2 the earliest cases were found in Louisiana

among the French, and in Minnesota and other Northwestern States

among the Norwegian immigrants, and a limited number in South

Carolina. It also, as known, exists in its colonies recently acquired.

In more recent years, as to be expected from our nearness to leprous

centers, imported cases, especially Chinese, have been met with in

California and the other nearby Coast States. Isolated cases in indi

viduals who have contracted the disease elsewhere are also encountered

from time to time in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and other cities.

Symptoms.—Leprosy presents varied and manifold symptoms.

The clinical aspects in some cases seem totally different from those

in others, and in others again are frequently of mixed character. There

are, too, in most instances, several stages of the malady, which are,

however, often ill defined. Owing to these facts it is customary, and,

upon the whole, more satisfactory as to clearness, to describe the dis

tinct types separately. Probably the best arrangement is a division

of the subject into: (1) Period of incubation; (2) period of invasion;

(3) macular type; (4) tubercular type; (5) anesthetic type; (6) mixed

type. One form usually shades slightly, moderately, or decidedly into

another, so that it can readily be understood that the manifestations of

either form may vary considerably.

1 See Abraham’s paper in Trans. Internat. Leprosy Conference.

2 D. W. Montgomery, “Leprosy in San Francisco,” Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, July

28, 1894; Dyer, “Report on the Leprosy Question in Louisiana,” Proceedings of the

Orleans Parish Med. Soc’y, meeting of June 11, 1894; Dyer, “Endemic Leprosy in

Louisiana,” Philada. Med. Jour., Sept. 17, 1898; Jones, New Orleans Med. and Surg.

Jour., 1877-78, vol. v, p. 673; Morrow, “Matters of Dermatological Interest in Mex

ico and California,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1889, p. 147; Hyde, “The Distribution of Lep

rosy in North America,” Trans. Cong. Amer. Phys. and Surg., 1894 (with full bibliog

raphy); J. C. White, “Leprosy in the United States and Canada,” Trans. Internat.

Leprosy Conference, 1897, vol. i; Bracken, “Leprosy in Minnesota,” Philada. Med.

Jour., 1898, ii, p. 1309; D. W. Montgomery (a white woman who contracted leprosy

in San Francisco), Lepra, Bibliotheca internationalis, vol. 1, Fasc 4, 1900; Burnside

Foster (case contracted in Minnesota), Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, Aug. 31, 1901; Dyer,

Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, Nov. 7, 1903; “Origin of Louisiana Leprosy,” Med. Library

and Histor. Jour., Jan., 1904; “Leprosy in North America,” Verhandl. v. Internat.

Derm. Cong., 1904, vol. 1; Daland, “Leprosy in Hawaiian Islands,” Jour. Amer. Med.

Assoc, Nov. 7, 1903; Ewing, “Leprosy as Seen in the Philippines,” Med. Record, Dec

15, 1906; Pollitzer, “Historical Sketch of Leprosy in the United States,” Jour. Cutan.

Dis., May, 1911, p. 361.

916

NEW GROWTHS

Stage of Incubation.—This is, so far as inference from the known

facts shows, extremely variable. The absence of a recognizable pri

mary lesion necessarily limits the field of observation on this point.

It has happened, however, that in some instances the malady can be

ascribed to exposure consequent upon a short visit to a region where

it is prevalent, the affection developing a variable time after the return

home—a country free from the disease. Such observations indicate

that the period of incubation, from the time of exposure to the first

manifestations, may be short or long, varying from several months

to some years, depending, doubtless, upon the receptivity and condi

tion of the individual and upon other—unknown—factors. As illus-

Fig. 228.—Leprosy of the maculo-anesthetic type, in a boy of fourteen; with also a

thickened macular anesthetic patch on the palm (courtesy of Dr. D. W. Montgomery).

trating the short extreme, Bidenkap, cited by Morrow,1 observed an

instance in which the disease developed a few weeks after the first

exposure, and Morrow himself had a case under his care in which the

disease appeared within ten months following a short visit to the Sand

wich Islands. On the other hand, some observers, among whom Dan-

ielssen, Boeck, and Leloir, have recorded cases having an incubation

period of ten to forty years. Doubtless the state of the health, the food

supply, climate, and surroundings, as well as the varying resisting power

of individuals, are responsible, in great part at least, for the great differ

ences in the length of time noted between exposure and the appearance

of invasion symptoms. It is not improbable, however, that in most cases

of apparent long period of incubation the disease may have already been

1 Morrow’s System, vol. iii (Dermatology), p. 566.

LEPRA

917

in existence for some time, but that the manifestations are of such mild

character that they escape observation.

Stage of Invasion.—This period varies within considerable limits,

averaging probably from several months to a year. The prodromata

of leprosy are frequently ill defined, and, unless occurring in leprous

countries or districts, and presenting something characteristic, are often

ascribed to simple ill health or considered manifestations of malaria,

tuberculosis, or some other malady. Chilliness, febrile action of an in

termittent type, malaise, disinclination to exertion, mental depression

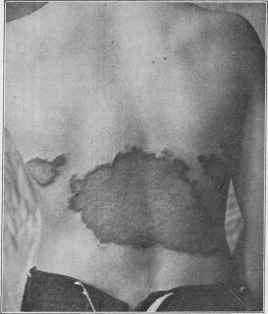

Fig. 229.—Macular leprosy patches, associated with tubercular infiltration of the face;

same patient as Fig. 231 (courtesy of Dr. L. A. Duhring).

or hebetude, debility and epistaxis, often associated with pain, altera

tions in sensibility, and motor weakness, variously present from time to

time irregularly. One, several, or all such symptoms may be noted, but,

as a rule, those most frequently observed are the chilliness and febrile

action, lassitude and debility, and pains, especially in the extremities,

and of a more or less paroxysmal character. Instead of chilliness there

may be well-defined rigors. The fever,1 if uncomplicated, is probably

1 Lewers, “A Note on Leprous Fever,” Brit. Jour. Derm., 1899, p. 388, gives a

good brief analytic review of this subject, with citations of opinions from important

works on the disease.

918

NEW GROWTHS

always more or less intermittent, and is, as well as other symptoms, due

to the presence of the bacilli or their toxins. While often an early mani

festation, it is frequently more pronounced later, along with the appear

ance of the cutaneous symptoms. Vertigo and cephalalgia are also not

uncommon manifestations in the invasion stage. In the anesthetic

variety of the disease, while chilliness, febrile action, and some of the

other symptoms named present, there is, as is to be expected, a prepon

derance of those of a distinctly neurotic character. Morrow considers

itching, often of a severe degree, to be one of the most common and char

acteristic signs of the invasion period. Formication, sensations of

tingling and burning, pricking pain, localized soreness or tenderness, a

numb or dead feeling, heaviness, stiffness with neuralgic pain, both of a

superficial and deep character, are also variously noted.

The import of such symptoms, as well as others of the invasion stage,

is often overlooked, however, until cutaneous evidences of the malady

show themselves. In many instances, it is true, these latter are the

first signs to which the patients give attention, the earlier symptoms

having been of a mild or obscure character or practically wholly absent.

Recent studies indicate, as first pointed out by Morrow, and since em

phasized by the observations1 of Sticker, Jeanselme, and Laurens, that

the first manifestations are rather determined toward the mucous mem

branes of the pharynx and upper air-passages than toward the skin;

and betrayed by alterations of the voice, such as husky or rough phona-

tion, rhinitis with an abnormally free nasal secretion, sometimes epis-

taxis, and an increase of the salivary secretion.

Macular Type.—Macular leprosy (lepra maculosa) is to be consid

ered more as a forerunner of the tubercular form, and occasionally also

of the anesthetic variety, than as a distinct type. The eruptive mani

festations may or may not have been preceded by several or more of the

invasion symptoms. The cutaneous phenomena consist of variously

sized patches, with or without infiltration, of a red, violaceous, brownish,

or blackish color. There may be an intermingling of depigmented

vitiligo-like spots, striæ, or areas, with those of a hyperpigmented char

acter, and these all may be so ill pronounced as to give the integument

a dappled appearance. In fact, this type can be said to be sometimes

made up of a mixture of morphea-like patches, leukodermic areas, and

more or less pigmented spots and patches. Some may be atrophic,

others somewhat thickened or lardaceous and firm. The eruption may

be slight and somewhat limited, or in some instances is quite extensive.

The color may be brownish or mahogany red or sepia tint, dependent

to some extent upon the complexion and race. Occasionally it may sug

gest an ecchymosis. Patches vary in size from a pin-head to a palm or

larger, as a rule being coin to palm-sized. There is sometimes a deeper

shade centrally, in others peripherally; if the latter, the patches may

assume a distinctly circinate aspect. The skin involved may be

otherwise apparently normal, slightly atrophic or thickened, and may

show slight hyperesthesia or be more or less anesthetic. Not infre

quently irregularly scattered blebs appear from time to time, usually

1 Sticker, Jeanselme, Laurens, Trans. Internat. Leprosy Conference, Berlin, 1897.

LEPRA 919

scanty in number. The febrile and other general symptoms, already

referred to, often present at intervals, at which times there is usually an

exacerbation in the cutaneous symptoms. The malady may persist

somewhat indefinitely as this type, with sometimes paralytic motor

symptoms and sensory disturbances, with variable mixture of more

pronounced evidences of the anesthetic type; or infiltration and nodula-

tion begin to present, and it passes partially or more or less completely

into the tubercular form.

Fig. 230.—Macular Leprosy—showing unusual circinate patches (courtesy of Dr.

Howard Fox).

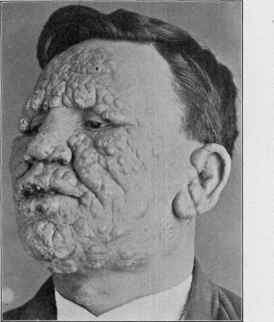

Tubercular Type (Tubercular Leprosy; Tuberculated or Nodular

Leprosy; Lepra Tuberculosa).—This is the more common expression of

the disease, and generally the form which is noted in a region when the

malady gains its first foothold. Later, after its existence in a community

for a long period, the milder or anesthetic type is noted to occur relatively

in greater and greater frequency. In tubercular leprosy the brunt of

the malady is seemingly borne by the integument. The earliest symp

toms are usually those described in the macular variety, which latter,

as stated, is generally to be considered an early stage of the disease.

The peculiar characters of the tubercular variety consist in the appear-

920 NEW GROWTHS

ance of tubercles and nodules, distinctly defined, or as more or less ill-

defined areas of infiltration, with subsequent ulceration. The skin,

more especially of the face, ears, and often other parts, is noted to be

thickened, seemingly hypertrophic, with an accentuation of the natural

lines. The region of the brow, particularly of the eyebrows, commonly

shows the earliest evident infiltration. Along with, as well as often

preceding, these characteristic lesions, scattered blebs and more or less

infiltrated, hyperesthetic or anesthetic, pinkish, reddish, or pale-yellow-

ish macules make their appearance from time to time, subsequently fading

away or remaining permanently.

When well advanced, the tubercular, nodular, or infiltrated masses

give rise to great deformity; the face, a favorite locality, becomes more

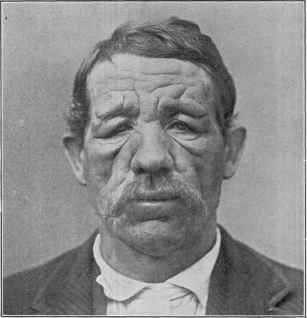

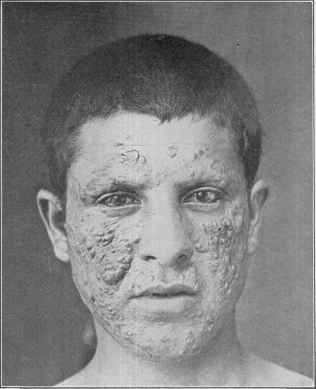

Fig. 231.—Leprosy of the tubercular type, associated with macular variety; the

tubercles not defined, but consisting of pronounced infiltration, especially about the

eyes and brow; same case as Fig. 229 (courtesy of Dr. L. A. Duhring).

or less roughly leonine in appearance (leontiasis). The hands are also

usually the seat of similar lesions, and not infrequently other regions

likewise present tubercles or areas of infiltration. As a rule, however,

the face, ears, and hands are the parts chiefly so involved.

The tubercles are brownish or brownish-yellow in color, vary in size

considerably, often attaining somewhat large proportions. They de

velop in most instances from macular, usually slightly or moderately

infiltrated, areas, although also often arising primarily upon skin seem

ingly previously unaffected. They persist almost indefinitely without

material change, or undergo absorption or ulceration; this last takes

place most commonly about the fingers and toes. Not infrequently

LEPRA 921

there is a partial or even complete disappearance of one crop of tubercles,

to be succeeded by another, and ordinarily of more pronounced char

acter. At such times the fresh outbreak is often preceded by febrile

action, chilliness, and other general symptoms. Others may undergo

some absorption and be gradually transformed into indurated, fibrous,

pseudokeloidal masses. Some may completely disappear and leave

behind atrophic, thinned, pigmented skin or cicatrices. Many tend,

however, after a more or less indefinite period, to undergo ulcerative

destruction, and this tendency, as already remarked, is most frequently

displayed with the tubercles and nodules of the extremities. The re

sulting ulcerations are of a shallow, indolent character, having a yellow-

ish-brown, viscid discharge, which sometimes dries to brownish, thickish

Fig. 232.—Tubercular leprosy of three years’ duration (courtesy of Dr. Howard Fox),

crusts. In some instances the ulcerative action extends deeply and may

lay bare ligaments and bones. Others after a time tend to heal, and

especially if cleanliness is maintained and antiseptic dressings applied.

In the course of time, and more particularly when ulcerative action is

pronounced, the lymphatic glands of the neck, groin, and axillæ become

enlarged, and not uncommonly finally break down and ulcerate; along

with this is noted also swelling of the lymphatics leading to these glands.

In addition to the integumentary changes, the mucous membrane

of the nares, mouth, pharynx, and other neighboring parts also shows

invasion. The eye likewise often suffers and exhibits surface tubercles

or infiltration. The hair, especially of the regions involved, sooner or

later shows impaired nutrition and falls out; this is frequently noted

922

NEW GROWTHS

about the eyebrows. The scalp hair, however, usually remains, as

this region is, according to almost all observers, peculiarly exempt from

leprous manifestations.1 The palms are likewise rarely invaded.2 The

nails do not, as a rule, seem to suffer directly, but their nutrition, as is

to be expected, is often impaired, and, as a result, there may be thinning

or thickening, irregularity, brittleness, opacity, etc There is commonly,

early in the malady, a disturbance of the functions of the sweat and

sebaceous glands; primarily there is often increased activity, but later

Fig. 233.—Leprosy, tubercular variety; lesions are also shown upon the cornea (courtesy

of Dr. J. A. Fordyce).

there is a partial or more or less complete arrest, and this may be localized

or somewhat general.

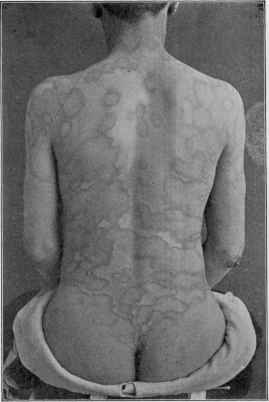

Anesthetic Type (Lepra Anæsthetica; Lepra Nervorum.—Anes

thetic leprosy, in which the brunt of the malady is borne by the nervous

system, is characterized chiefly by anesthetic and atrophic manifesta-

1 Morrow, “A Case of Macular Lepride of the Scalp—with Remarks on the Locali

zation of Leprous Lesions,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1900, p. 10, reports a case in which the

scalp showed macular manifestations; Pernet, Brit. Med. Jour., Nov. 11, 1905, p. 1280,

reports 2 cases in which the scalp was involved.

2 D. W. Montgomery, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1899, p. 445, noted an instance with a

maculo-anesthetic leprid upon the palm; a case with a similar circinate patch in this

region, in addition to manifestations on other parts, recently came under my notice.

LEPRA 923

tions. The latter are usually more or less limited to the hands, feet, and

face. Its development is an insidious one, and it is not infrequently a

part of or a sequence of the macular form. Following or along with the

precursory symptoms denoting general systemic disturbance, or inde

pendently of any prodromal indications, a hyperesthetic condition, in

localized areas or more or less general, is observed. As a rule, febrile

attacks, or the pseudomalarial aspect, is not a usual, or at least not so

constant, accompaniment of this type. Lancinating pains along the

nerves, particularly of the extremities, and an irregular, scattered, pemphi-

goid eruption are, however, commonly noted. The malady may present

nothing further than these various manifestations, often along with

occasional attacks of, or more or less persistent, pruritus, for an indefi

nite time, ordinarily one to several years. Sooner or later there follows

the special eruption, coming out from time to time, and consisting of sev

eral or more, usually non-elevated, well-defined, pale-yellowish patches,

1 or 2 inches in diameter. They rarely present in numbers, but gen

erally present singly, new areas appearing from time to time. They

are found most frequently upon the back, shoulders, dorsal surface

of the arms, thighs, about the elbows, knees, and ankles. The face

also may show the eruption. There is often a symmetric distribution.

Leloir noted an instance of double zoster-like arrangement on the chest.

As a rule, they are at first neither hyperesthetic nor anesthetic, but may

be the seat of slight burning or itching. They spread peripherally, and

tend to clear in the center. The patches eventually become markedly

anesthetic, and the overlying skin and the skin on other parts as well

becomes atrophic and of a brownish or yellowish color. In many in

stances when first appearing they are of a sepia-brown shade, and some

times of a bluish-red color, and usually more pronounced at the border

portion. Occasionally if several are close together coalescence gradually

takes place, resulting in gyrate patches, with a well-defined, sometimes

slightly elevated, reddish periphery, and a pale or leukodermic atrophic

central portion. In fact, instead of the eruption presenting itself as

yellowish-brown areas, of the features described, the earliest patches may

be of a vitiligo-like character. In some cases there is depigmentation,

extending over considerable surface.

The areas are frequently preceded by sensory disturbance, such as

formication, burning, or stinging sensations. While they are in their

first appearance sometimes hyperesthetic, after a variable time, usually

soon afterward, there is anesthesia, especially centrally. Not uncom

monly the central portion becomes anesthetic, while hyperesthesia is

noted in the spreading border. In some cases, or in some stages of the

malady, the anesthesia does not confine itself to the immediate areas,

but may involve considerable surface, or even an entire region supplied

by an affected nerve. While ordinarily the nervous disturbance primar

ily does not compromise the tactile sense, consisting at such period of

hyperesthesia, analgesia, and thermo-anesthesia, later the sensory func

tions are wholly abolished.

As the disease continues and the nerve involvement becomes more

pronounced atrophic symptoms are noted to ensue. The subcuta-

924

NEW GROWTHS

neous tissues, muscle, hair, and nails undergo atrophic or degenerative

changes, and these changes are especially observed about the hands

and feet. These parts become crooked, thinned, emaciated, and other

wise distorted. Surface ulcers appear, either spontaneously or as the

result of knocks or other injuries. The muscles atrophy, the fingers

become drawn up and flexed, producing the so-called “leper claw.’’

Finally the bone tissues are involved, the phalanges dropping off or dis

appearing by disintegration or absorption (lepra mutilans). The toes

and feet are similarly affected, and not infrequently, especially in those

who go barefooted, a deep plantar ulcer forms. The process may not

stop at disintegration and destruction of the fingers and toes, but the

hands and feet may gradually be wholly lost. The ulnar and peroneal

nerves and other nerves of

the extremities seem to be

especially prone to the damag

ing influence of the bacillus

invasion. The ulnar nerve

particularly is considerably

thickened, either uniformly or

irregularly, and can usually be

felt as a thick, tense cord, and

is often painful upon pressure.

In addition, owing partly to

the atrophy of the glandular

structures and the consequent

suppression of the sweat and

sebaceous secretions, there is

often a thinned, atrophic-look-

ing condition of the skin of the

arms and legs, which is gen

erally of a dirty yellowish or

brownish color, and presents

a somewhat tense appearance,

and with thin, flaky, or branny

scaliness. Occasionally the

skin is somewhat wrinkled.

In occasional cases the skin of

the trunk likewise exhibits similar changes. The atrophic action also

often involves the face, and along with the paralytic symptoms, which

sooner or later presents, give rise to considerable facial disfigurement.

The face is sometimes drawn to one side. The eyelid muscles are often

involved, and, in consequence, and also partly owing to the loss of

eyelashes, the eyes not being properly protected, inflammation, ulcera-

tion, and opacities ensue.

Ulcerations are not so common a feature of the anesthetic as of

the tubercular form, and are chiefly the result of trophic influence,

arising principally from dry or moist gangrene, and from knocks or

other injuries.

The mucous membrane, especially of the mouth, soft palate, uvula,

Fig. 234.—Leprosy of the tubercular type,

on face, associated with anesthetic type; same

case as Figs. 235 and 238.

LEPRA

925

and back of the pharynx, shows loss of sensibility and other nervous

disturbance, and there is serious interference with the act of deglutition,

often giving rise to regurgitation through the nostrils.

Mixed Type.—The mixed form of leprosy is, as the name signifies,

characterized by features of the several types described. The early le

sions are usually, as in the other forms, those of the macular type. Later

there is often at first the development into the anesthetic or tubercular

expression of the disease, and which may persist as such for a variable

time, and then gradually

present symptoms of the

other variety. The dis

tinctly anesthetic form of

the malady may, there

fore, sometimes sooner or

later have added tuber

cular and nodular infiltra

tions, and with subse

quent ulceration; the tu

bercular form likewise may

present after a time fea

tures of the anesthetic

type, not infrequently,

however, the clinical fea

tures are of mixed char

acter from the beginning.

Course.—Leprosy

runs a chronic persistent

course, with, in many

cases, remissions, or even

temporary or more or less

prolonged intermissions.

Exacerbations in the cu

taneous phenomena occur

from time to time, and

at such periods there are

generally preceding and

accompanying constitu

tional symptoms of mal

aise, debility, febrile ac

tion, and chilliness or

distinct rigors. These are much less common, however, in the anes

thetic variety, and not infrequently are practically absent. The in

tegumentary lesions become slowly more pronounced and numerous, and

while the tubercles and nodular masses and infiltration may undergo

absorption, new outbreaks predominate over retrogressive changes.

More commonly these lesions show ulcerative changes. The nervous

form of the disease, as already described, increases, as a rule, steadily,

but is much less rapid in its progress than the tubercular form, usually

lasting from ten to thirty years, averaging probably twelve to fifteen.

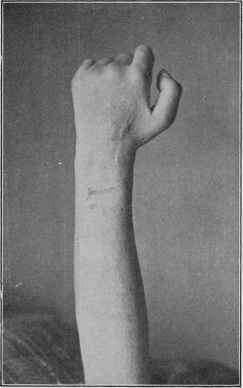

Fig. 235.—Leprosy, showing paralysis and atro

phy of some of the extensor muscles, and the “leper

claw” of the anesthetic type; faint macular anes

thetic area shows on forearm; same case as pre

ceding, with tubercular type on face.

926 NEW GROWTHS

In tubercular leprosy death results in almost half the cases from

the direct effect of the disease, either from exhaustion or involvement

of the air-passages or of internal organs. Renal and lung complications

Fig. 236.—Anesthetic leprosy—showing “claw hand” with ulcerations (courtesy of

Dr. J.M.Winfield).

carry off almost as great a number. The remainder die from anemia,

or enteric complications with colliquative diarrhea. In the anesthetic

form the end comes from the direct action of the leprous poison, from

Fig. 237.—Anesthetic leprosy, showing characteristic mutilation (courtesy of Dr. J. M.

Winfield).

exhaustion, muco-enteritis, long-continued digestive disorders, or other

complications. Pulmonary and renal disorders are not encountered

as often in this form as in the tubercular variety.

LEPRA

927

It is not improbable, however, that the pulmonary and enteric

maladies which bring the fatal end in leprosy cases are, in reality, not

complications, as usually understood, but are themselves of leprous

character. Arning believes that the supposed intercurrent pneumonia

and tuberculosis, and the diarrhea or dysentery, are due to leprous

infiltration—which he denominates respectively phthisis leprosa and

enteritis leprosa. Beaven Rake’s1 conclusions are practically the same.

The culture experiments with fragments of assumedly phthisical lung

or tuberculous viscera from lepers have, as he states,2 so far been unsuc

cessful, this tending to confirm the view that these conditions are lep

rous and not really tuberculous. As to kidney complication, this same

observer3 found, in 78 autopsies, some form of nephritis in 23 cases, a

percentage of 29.4. He noted a much longer duration of life in these

cases when occurring in the anesthetic variety than in the tubercular

Fig. 238.—Leprosy, with paralysis and atrophy of extensor muscles, and some small

ulcerations on toes, and slightly scurfy skin; same case as Fig. 235.

form, which he attributes to the fact that in the latter variety the sweat-

glands are involved earlier and to a more serious extent, thus throwing

more strain on the kidneys.

Etiology.—The direct cause of leprosy is now accepted to be

a specific bacillus—the bacillus lepræ. The discovery by Hansen, in

1874, has completely negatived the hereditary theory formerly so strongly

held. It is true that the evidence points to the fact that certain individ

uals or families may, as likewise now believed regarding tuberculosis, show

a readier susceptibility when exposed to invasion. It is certain, too,

1Beaven Rake, “The Significance of Visceral Tuberculosis in Leprosy,” Brit. Jour.

Derm., 1890, p. 33 (based upon a study of 90 autopsies).

2 Beaven Rake, Brit. Med. Jour., Aug. 4, 1888.

3 Beaven Rake, “The Kidney Lesions in Leprosy Considered in Relation to the Skin

Changes,” Brit. Jour. Derm., 1889, p. 213 (with citation of the opinion of others as to

the complication, with references).

928

NEW GROWTHS

that the liability to successful implantation of the organism is measurably

increased by such predisposing influences as climate, soil, abode, food,

and habits. It is known that the malady is most prevalent in tropical

and subtropical countries, although it is also common in some cold

climates, as Norway, Iceland, and elsewhere. It is, moreover, distinctly

a disease of the coast and nearby waterways; it also occurs, however,

inland, and in high regions likewise, although to a relatively slight extent.

The method by which the organism gains access is not known.1

Recent observations (Morrow, Sticker, Jeanselme, Laurens, Babes,

von Peterson, Flügge, Besnier, Glück, Schaeffer) indicate that the

mucous membrane of the nose, and probably of the mouth also, may

be a not uncommon source of communication and infection.2 Schaeffer3

refers to experiments on this point. Slides were placed in the vicinity

of leprosy patients while they were reading aloud, and subsequently

examined, disclosing the presence of large numbers of bacilli. It is not

improbable, also, that entrance may take place through some abrasion

in the skin (Lassar, Arning, von Peterson, Ehlers, Geill). Geill4 calls

attention to the fact that in tropical countries, with the people who go

barefooted, the first lesions are seen frequently upon the feet—in 50

per cent, of his own cases. It is known that the bacilli can be found

in the feces (Boeck).5 Vaccination has exceptionally been blamed for

the introduction of the organisms, but there is scant reliable evidence

on this point.6 There is a growing belief that the malady is not directly

contagious or inoculable from man to man, but that there is an inter

mediate host, or insect carrier, as now generally believed as to malaria,

and it is one that might explain many apparent contradictions.7 Hutch-

inson8 has long held, as is well known, the opinion that in the eating of

fish, especially raw or salted, is to be found the cause of the malady;

lately he has added the suggestion that the bacillus may gain access in

1 See Morrow’s interesting paper, “Sources and Modes of Infection in Leprosy,”

Trans. Amer. Derm. Assoc. for 1899, p. 113; Mugliston, Jour. Trop. Med., 1905, p. 209,

suggests that the itch mite may possibly be the means of communication—having the

leprous bacillus in or simply on its tissues when it enters the skin.

2 Mewborn, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1903, p. 23ó, found numerous bacilli in the nasal

secretion taken from a case observed by Fordyce.

3 Schaeffer, Trans. Internat. Leprosy Conference, Berlin, 1897.

4 Geill, ibid.

5 Boeck, Festschrift, Unna (1910, Bid. 1, p, 436), and Dermatolog. Wochenschr., Oct.,

1912, lv, p. 1267 (discusses the possibilities of spread of disease by this source).

6 See Baum’s paper, “Leprosy and Vaccination,” Med. Standard, 1893, p. 163.

7 Goodhue (Boston Med. and Surg. Jour., 1906, vol. cliv, p. 357) states that he has

found the bacillus in the bedbug and in the mosquito, but as yet this statement remains

without corroboration by others; Currie, “Mosquitoes and Fleas in Relation to the

Transmission of Leprosy,” Public Health Bull., 1910, Washington, D. C. (full abs.

in Jour. Trop. Med., May 1, 1911), made some experiments in the laboratory at Hono

lulu, with the results: mosquito, chiefly culex cubensis, negative, as the proboscis is

inserted into a blood-vessel obtaining bacilli—free blood; domestic flies will convey the

bacillus from a discharging leprous ulcer to the skin of a healthy person in the neighbor

hood; Engelbreth (Dermatolog. Wochenschr., 1912, liv, pp. 700 and 723), in an interesting

paper on the origin of the disease, endeavors to show that leprosy has flourished in all

countries where the goat flourished, and tends to disappear where these give way to the

breeding of sheep and cattle; he believes that an internal disease in the goat, closely

resembling tuberculosis, is transmitted to man (through milk, etc), and results in

leprosy.

8 Hutchinson, “Leprosy and Fish-Eating,” London, 1906.

LEPRA

929

this way. His views as to this food-cause are negatived by the general

observations of others. It is not at all unlikely, however, that its en

trance, in some cases at least, may be through the food.

While one, upon going thoroughly over the clinical evidence, must

admit the communicability of the disease, yet there are other unknown

factors in addition to the active one—the bacillus—which seem to be

necessary. Hereditary tissue weakness, climate, food, abode, and

habits are, doubtless, therefore contributing. If its successful communi-

cability depended upon the bacillus alone, the examples of the con

tagiousness of the disease should be common, instead of rare.1 Its con

tagiousness, under favoring circumstances, is shown in the rapid spread

in Hawaii, and more recently the suggestive increase in Louisiana (Dyer).2

But even in Hawaii the contributing influence of race, poor food, and

other factors is disclosed by the fact that the leper population consists

almost entirely of Hawaiians and half castes, less than 3 per cent, are

Chinese, with a few other foreigners—British, American, German, etc.—

not exceeding a dozen. As von Düring well remarks, however, all nega

tive evidence brought forward as to its non-communicability is valueless

in the face of one positive fact to the contrary. And though these posi

tive data are, in my judgment, relatively scanty, still they are sufficient

to make us look upon the existence of cases in our midst as of possible

danger, although this is in civilized, well-fed, and well-cared-for communi

ties exceedingly remote.3

It is generally admitted that the anesthetic type is not so contagious

as the tubercular; and it is also commonly believed that the form of the

disease in a community which is usually primarily tubercular, gradually,

after years, loses its virulent character somewhat, and that it subse

quently persists in the anesthetic form. Zambaco4 and a few others

would also have us believe that its virulence becomes still further atten-

1Hutchinson states (Brit. Med. Jour., June 29, 1889) that not a single sporadic

case is ever now seen in England; the cases there are all imported. Bronson says (Jour.

Cutan. Dis., 1895, p. 428) of New York: “we have had lepers in this city for many

years, and yet there is not a single case on record where local contagion has occurred.”

Lutz (ibid., 1892, p. 477), speaking of his experience and observations in South America

and the Hawaiian Islands, says: “Contagion even by intimate and prolonged contact

is by no means frequent in families living in a civilized way and in easy circumstances.”

Hallopeau (Trans. Internat. Leprosy Conference, Berlin, 1897) says that “in Paris up to

the present no case has been known to arise there”; and Besnier (ibid.) also states

that “in Paris, at the Hôpital St. Louis, lepers are not isolated, and notwithstanding

this no instances of contagion have ever occurred”; Thompson (Lancet, Mar. 5, 1898)

shows that in Victoria and Australia, where lepers have mingled freely with the com

munity, the disease is on the decrease. Kaposi (Wiener klin. Wochenschr., No. 45,

1898), while admitting that from a pathologic point of view the malady is infectious,

holds that clinically it is not contagious. Zambaco, who is still a champion of the hered

itary nature of the disease, states that he has never seen a case originating in contagion.

2 Dyer, Philada. Med. Jour., Sept. 17, 1898.

3 Bracken, ibid., Dec 17, 1898, states that it is quite possible, judging from his

own observations, for leprosy to die out in certain favored sections of our country,

such as Minnesota, without segregation, provided the importation of lepers be dis

continued.

4 Zambaco, Trans. Internat. Leprosy Conference, Berlin, 1897; see also Leloir’s

interesting paper on this point, “Existe-t-il dans des pays réputés non lépreux, en France

et en particulier dans la region du nord et a Paris, des vestiges de l’ancienne lépre,”

Bull, de l' Acad. de Méd., Paris, 1893, p. 215; a good abstract in Brit. Jour. Derm., 1893,

p. 129; see also references under Morvan’s disease.

59

930 NEW GROWTHS

uated, and that the disease is finally exemplified in many cases of the

maladies known as syringomyelia, scleroderma, morphea, sclerodactylia,

Raynaud’s disease, and progressive muscular atrophy (Aran-Duchenne),

considering them to be modified or weakened forms of lepra.

Pathology.—The bacillus is now fully accorded the rôle of

starting and producing the pathologic changes, and which has in

recent years received considerable study by many investigators. The

bacillus is a slender, rod-like, straight or very slightly curved parasite,

averaging about 1/5000 inch in length (from one-half to three-fourths

the diameter of a red blood-corpuscle); and its thickness is about one-

fourth to one-fifth of its length. According to Cornil, the longest are

found in parenchymatous organs, while those found in the skin nodules,

owing to compression, are, as regards size, less developed. Morpholog

ically they are very similar to tubercle bacilli, and their differentiation

is not always easy. Lepra bacilli are, however, in relatively greater

abundance in the tissues, usually occur in clumps, groups, or masses,

are smaller and less uniform in diameter than the tubercle bacilli. They

also exhibit readier reaction to staining agents, “dependent upon micro-

chemical reaction of the investing membrane of the bacillus to acids,

alkaline and anilin dyes.” They are best demonstrated by staining the

section of tissue or débris of a broken-down nodule by Ehrlich’s process

with fuchsin, and methyl-blue as a contrast (Crocker). While the

bacilli are sometimes found more or less generally distributed in the

tissues, they have certain predilections. They are usually most abundant

in the diffuse and nodular infiltrations, in the connective tissue of the

peripheral nerves, in the lymphatic glands and spaces, and sebaceous

glands (Babes and Unna); but are rarely to be found in the true maculo-

anesthetic patches, unless associated with some infiltration. They are

also found in the liver, spleen, kidneys, in the testicles (Neisser and

others), and, according to Arning, also in the ovary. In fact, in well-

advanced cases, more especially in the tubercular form, scarcely any

organ escapes. The physiologic secretions remain free so long as the

secreting tissue or membrane does not become the seat of leprous de

posits. The blood-vessels, except those peripherally involved in the

leprous infiltrations or in the last stages of the disease, rarely contain

bacilli.

The earlier reports (Campana and Ducrey, Hansen, Neisser, Carras-

quilla, Van Houtum and Emile-Weil) of alleged moderately successful

culture of the bacillus have been looked upon with considerable question;

but the later trials (Kedrowski, Clegg, Duval, Brinckerhoff, Currie and

Holman, and others) seem to have been more fortunate, but with some

slight puzzling diversity in the results. Duval and Wellman,1 from a

1 Duval and Wellman (“A Critical Study of the Organisms Cultivated from the Le

sions of Human Leprosy, with a Consideration of their Etiologic Significance,” Jour.

Cutan. Dis., 1912,p. 397), as a result of their own researches, reached the following con

clusions: (1) From a bacteriologic study of 29 cases of leprosy, an acid-fast bacillus was

discovered in 22. (2) A chromogenic strain similar in all essentials to that described by

Clegg was recovered from 14 cases, which under certain conditions grows as (a) non-

acid-fast streptothrix, (6) non-acid-fast diphtheroid, and (c) an acid-fast bacillus. (3)

Eight cases yielded an organism which was distinctly different from Clegg’s bacillus in

its biologic character, growing only upon special medium and not producing pigment.

LEPRA

931

review of the subject and their own investigations, conclude that two,

possibly three, different organisms have been cultivated from the specific

lesions of leprosy, namely: (1) a non-acid-fast diphtheroid (Kedrowski),

(2) an acid-fast chromogenic bacillus (Clegg), and (3) a permanently

acid-fast bacillus (Duval). Williams has grown four different types of

organisms, including a Gram-positive non-acid-fast streptothrix, which,

however, he believes to be different phases of the same organism. The

earlier experimental animal inoculations (Hansen, Köbner, Damsch,

Rake, Campana, Profeta, Vossius and Melcher-Orthmann) were, accord

ing to Neisser’s examination of the question, practically negative; in a

few instances there was a suspicious local growth. More recently Duval

and Gurd, Sugai, Monobe, Bayon, Rost and Williams, and others seem

to have succeeded in producing the disease, or at least conditions simulat

ing it, in the Japanese dancing mice, white mice, rats, and monkeys—

in most of these later instances the inoculating material consisted of the

cultured organism.1 According to Duval and Gurd the bacilli may live

for more than a year outside of the body. The reported successful inocu

lation (Arning) some years ago in man must be viewed with suspicion,

inasmuch as the subject belonged to a leprous family.

If a section of recent nodule is examined, it is observed to consist

(Neisser) of a cell-mass separated by sparse fibrillary intermediate

tissue; the cellular elements, mostly rounded in form and primarily like

lymph-corpuscles, undergo increase in size and reach four or five times

their original volume, constituting the so-called lepra cells and the giant-

cells found in leprous tissue. The nucleus, likewise, shows similar in-

(4) Animal experiments undertaken for the purpose of differentiating the two types

removed from the human leprous lesion and to fix their etiologic status were not re

garded as conclusive. (5) Serologic tests, especially those performed with highly

immune sera, suggested that the bacillus of Clegg was not related to Duval’s non-

chromogenic, slow-growing culture of leprosy. (6) The rôle played by the chromogenic

bacillus of Clegg in the production of leprosy was unsettled. (7) The non-chromogenic

strain, while behaving according to most of our notions of a pathogenic organism, had

not yet been proved to be the cause of leprosy, although it was probable that it might

be so, and the writers considered that it deserved more serious attention than any strain

cultivated from the human leprous lesion. (8) The wide variation in morphology and

staining reactions for certain cultures which subsequently become rapid growers and

chromogenic explained that interpretation of European writers, that the Bacillus lepræ

is a bacterium of such pleomorphism that it can be recognized as a diphtheroid, a

streptothrix, and an acid-fast bacillus.

1 The reader desirous of pursuing further the subject of cultures and inoculation

experiments is referred to the following additional contributions: Macleod, “A Brief

Survey on the Present State of Our Knowledge of the Bacteriology and Pathologic

Anatomy of Leprosy,’’ Brit. Jour. Derm., 1909, p. 309; Sugai, Lepra, 1909, viii, p. 203;

Clegg, Philippine Jour. Sci., 1909, iv, p. 403; Duval Jour. Exper. Med., 1910, xii, p.

649, and 1911, xiii, p. 365; and “The Experimental Production of Leprosy in the Mon

key (Macacus rhesus),” with review, Penna. Med. Bull., 1911, p. 665; Duval and Gurd,

Arch. Int. Med., 1911, vii, p. 230, and “Experimental Leprosy and Its Bearing on

Serum Therapy,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1911, p. 274; Currie, Clegg, and Holman, “Studies

upon Leprosy: Cultivation of the Bacillus of Leprosy,” Public Health Bulletin, Sept.,

1911, No. 47, Washington, D. C, p. 3, (chronologic review of literature and their

own work); Bayon, Jour. London School Tropical Med., 1911, 1, p. 45; and Brit. Med.

Jour., Feb., 24, 1912; Alderson, “Artificial Cultivation of Lepra Bacillus in Hawaii,”

California State Med. Jour., 1911, ix, No. 3; Rost and Williams, “Scientific Memoirs of

Gov’t. of India,” 1911, No. 42—abs. in Brit. Jour. Derm., 1912, p. 164; Williams,

Indian Med. Gaz., “Review Editorial,” Lancet, 1912, clxxi, No. 4584; Monobe, Japan-

ische Zeitsch. für Derm, und Urol., Feb., 1912, xii, No. 2, p. 8—abs. in Jour. Cutan.

Dis., 1912, p. 449.

932

NEW GROWTHS

crease, and some cells may contain several nuclei. The cells are most

plentiful in the neighborhood of the blood-vessels, which are numerous

and the vascular supply abundant. Leprous growths are, however, less

vascular than ordinary granulation tissue, and therefore undergo retro

gressive changes more slowly. The epidermis is not involved in the

specific morbid process, and never contains the parasites. The his-

topathologic changes are especially noted in the papillary layer, in the

main body of the corium and the subjacent tissue. According to Neisser

and others, a lepra tubercle or nodule is primarily composed of granula

tion cells. The deepest cellular layer, that in the subcutaneous tissue,

is noted to contain, along with many unchanged lymph-cells, the smallest

and most recent tumor cells, and but relatively few bacilli. The cells

show gradual enlargement in the higher layers. The oldest, topmost,

layers are divided from the rete by a stratum of subepidermal connective

tissue; the epithelial layer, except as to the disappearance of its inter-

papillary dippings, is otherwise normal, although showing increased

pigmentation. More especially in the upper layers of the tumor are

seen peculiar large, rounded, sharply circumscribed accumulations, the

so-called “globi,” composed of cells very densely infiltrated with bacilli

and their products, and undergoing degeneration. Besides the large

lepra cells there are small cells apparently identical with migratory

cells; and small connective tissue cells which show here and there en

largement from infiltration with bacilli.

There is a difference of opinion as to whether the bacilli lie within

or without the cells. Virchow, Neisser, and almost all others consider

that they are almost exclusively within the large round lepra cells,

whereas Unna,1 Herman,2 and a few others maintain that they are

chiefly found in lymph-spaces, Unna asserting that the lepra cell is

nothing more than a glœa-like mass formed by degeneration of the bacilli.

It is now recognized that a large proportion of the bacilli found in the

tissues are dead; that even in young newly formed lepromata dead

bacilli occur, while in older lesions the majority of the bacilli are dead

(Macleod). Virchow believed the fixed connectivetissue cells to be

the mother-cells of the subsequent granulation tumor. Thin and

Neisser hold the view that the lepra cells develop from emigrated white

blood and lymph-corpuscles.

In the anesthetic variety the chief changes are in the nerves. Vir-

chow, Neisser, and others place the primary pathologic process in the

peripheral and cutaneous nerves, due to leprous new formation, leading

to compression and atrophy of the sensory and trophic fibers. The

nerves most frequently affected are the ulnar, median, radial, musculo-

cutaneous, intercostal, humeral, and peroneal. It is generally believed

that these changes are practically limited to the peripheral nerves,

Hansen, Hillis, Leloir, Neisser, and others finding the spinal cord and

brain, in the cases examined by them, normal. In more recent years,

however, several observations seem to point to the possibility of central

1 Unna, Histopathology.

2 Herman, “The Bacillus of Leprosy in the Human System at Different Periods of

its Growth,” Trans. Internat. Leprosy Conference, 1897.

LEPRA 933

nerve involvement; Chassiotis1 found in one instance investigated by him

bacilli in the spinal cord.

Diagnosis.—The recognition of a well-developed case of lep

rosy of either type is, as a rule, not attended with difficulty. It is an

entirely different matter, however, in many instances in the earlier

stages, or in those of advanced period if the disease is atypical.2 In the

invasion and early eruptive stage the prodromal symptoms of chilliness,

febrile action, with subsequent free perspiration, so often observed in

the tubercular form, may be, and often are, confounded with those of

malaria. The erythematous areas may be confused with simple ery

thema, although they are commonly larger, frequently tend to show in

filtration, and are slow in undergoing involution. If to these symptoms

could be added sensory disorders, usual in anesthetic leprosy, together

with a history of exposure, a strong suspicion could be entertained, and

probably a positive opinion reached.

In the anesthetic variety the prodromal symptoms are also usually

of variable character and intensity, and the pain and motor weakness

often attributed to rheumatism or neuralgia; the other disorders of sen

sation, such as hyperesthesia, sensations of burning, tingling, numbness,

formication, and pruritus, one or several of which may be present, are

often wrongly interpreted as pointing to neurasthenia or other nervous

disorders. When, however, such a patient is living or has been living

in a district where the disease prevails, the possibility of leprosy is to be

borne in mind. This would be materially strengthened by the presenta

tion of erythematous patches of a dull red color, and of persistent char

acter, with a tendency to clear centrally while extending at the border,

the central part generally becoming whiter than normal and anesthetic.

Such areas are, however, to be distinguished from those of morphea and

vitiligo.

Later in the course of the malady the tubercular form is to be differ

entiated mainly from lupus vulgaris, the tubercular syphiloderm, and

granuloma fungoides. In the first the eruption is usually quite limited,

at least relatively, and most commonly confined to a portion of the face,

is of slow development, and frequently spreads from one center. More

over, it, as a rule, lacks the infiltration generally noted in leprosy. The

tubercular syphiloderm is also a limited eruption, and differs materially

from that of leprosy by the fact that it tends to occur in segmental,

crescentic groups or serpiginous tracts—a formation rarely, if ever,

noted in leprous infiltrations or tubercles. Both lupus and syphilis are,

moreover, ordinarily wanting in any suspicious prodromal symptoms.

Granuloma fungoides and well-marked tubercular leprosy have also

sufficient in common to give rise to possible confusion, but the early

eczematoid manifestations of the former, with the usually accompanying

itchiness, its more general distribution, the brighter red color, often serve

to differentiate; in the later stage the peculiar fungoidal ulcers would be

distinctive.

1 Chassiotis, “Ueber die bei der anästhetischen Lepra in Rückenmarke vorkom-

menden Bacillen,” Monatschefte, 1887, vol. vi, p. 1039.

2 Thin (loc. cit.) cites numerous examples of errors in diagnosis by observers experi

enced in dermatology.

934

NEW GROWTHS

The anesthetic form in the more advanced stages is to be distin

guished chiefly from syringomyelia, to which it sometimes bears a

striking similarity. The various sensory disorders, however, when

taken together with the lesions of the bones and joints of the extrem

ities, with the mutilations and deformities, commonly observed in ad

vanced stages of leprosy, with the history, often, of preceding pem-

phigoid eruption, and vitiligo or morphea-like patches, are quite char

acteristic.

In cases of doubtful nature, whatever the type of the malady, the

final decision is often to be based upon the presence of the special bacillus,

as determined by repeated examinations. Shepherd1 advises, when

the question of immediate diagnosis is one of great urgency, cutting

down on the ulnar nerve, removing a portion, and examining for bacilli.

It is commonly believed that leprous patients give a positive Wasser-

mann, but there are exceptions to this.2

Prognosis.—The outlook for leprosy patients is unfavorable, a

fatal termination, with occasional exceptions, being the rule, although

the end may not be reached for a number of years. The tubercular form

is the most grave, the mixed variety the next, and the anesthetic the

least. The statistics of the Trinidad Asylum, according to Rake,3 show

that the average duration is eight and one-half years. In some instances,

especially of the anesthetic variety, it may be fifteen to twenty years

or more. Patients are not infrequently carried off by intercurrent

disease, although, as already referred to, apparently independent organic

affections are often, in fact, due to leprous invasion and infiltration.

Under the most favorable conditions much can be done, and doubtless

an occasional cure—a symptomatic cure at least—brought about.

There seems scarcely question that mild or abortive types occur,

though doubtless but rarely. Hansen and Looft, in quoting Daniels-

sen’s observations as to the Norwegian hospital, “that the results of

treatment were nothing to boast of, but show that leprosy at its com

mencement can be cured,'’ add the reservation “that the cure is not due

to the treatment, but to the natural development of the disease.” One

cannot go over the literature without recognizing the fact that in excep

tional instances patients recover, or at all events the malady remains

permanently quiescent. Impey4 is strongly of the opinion that some

cases, especially the anesthetic, undergo spontaneous cure, and believes

that in many so-called lepers the malady has already run its course, and

that the effects alone remain, and may go on from the damage done the

nerves. He quotes Hansen’s studies as showing that the latter observer

“had never found bacilli in the nerves of a chronic case, . . . and that

1 Shepherd, “Notes on a Rapid Method of Diagnosis in Leprosy,” Jour. Cutan. Dis.,

1903, p. 476.

2 Bloombergh, “The Wassermann Reaction in Syphilis, Leprosy, and Yaws,”

Philippine Jour Sci., Oct., 1911, p. 335 (doubts a positive reaction in leprosy, and thinks

before accepting the same present or antecedent frambesia and syphilis must be

excluded—of decided importance in countries where these diseases prevail; references

to pertinent papers are given).

3 Rake, Report on Leprosy in Trinidad, 1885.

4 Impey, “The Non-Contagiousness of Anesthetic Leprosy,” Trans. Internat. Lep

rosy Conference.

LEPRA

935

he had examined the bodies of many of these patients after death, and

found no bacilli in any organ.” Thin, D. W. Montgomery, G. H. Fox,

Ehlers, Hallopeau, Dyer, and others1 have in recent years reported cures

of the disease, spontaneously or as the result of treatment.

Under the most favorable circumstances of change of residence to

a non-leprous district, improved hygiene, good food, supporting and

tonic treatment, cleanliness, and aseptic applications, it seems, there

fore, not improbable that exceptionally cases get well, or at least the

disease ceases to be active.

Treatment.—The management of leprosy naturally includes a

consideration of the means of prevention. There are still great dif

ferences of opinion as to the necessity of segregation, and each side of

the question has much in its support. The conclusions of the Inter

national Leprosy Conference at Berlin, 1897, were, upon the whole,

in favor of this, with certain qualifications as to its practice, depending

upon local conditions.2 It is generally recognized that the anesthetic

cases are much less dangerous to a community than the tubercular form,

and segregation less urgent. The necessity of segregation in districts

where the cases are sparse, with no tendency to spread, and where lepers

can be properly cared for at their homes, is questioned by many of con

siderable experience. As already stated, the imported cases in Paris,

London, Vienna, Berlin, New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other

places where the disease is not endemic have never given rise to

others.

The treatment of leprosy has first in view the maintenance of the

patient’s general health by hygienic and other measures, and the em

ployment of such tonics as may seem demanded. The value of change

of abode to a non-leprous country, when possible, has already been

alluded to, and will in some instances stay, and probably always delay,

the progress of the malady. There are certain remedies for which

special claims have been made from time to time by different observers.3

The most important, and those which have received the greatest support,

are Chaulmoogra oil (Le Page), gurjun oil (Dougall), and nux vomica or

strychnin.

Chaulmoogra oil (oleum gynocardiæ, from the seeds of the Gyno-

cardia odorata) is given in doses varying from 5 minims (0.33) to 1½

drams (6.) or more three times daily. It is administered in milk, in

emulsion, or in capsules. As a rule, its good effects are obtained only by

the larger doses, and these cannot always be reached, owing to the fact

that the oil is so prone to disturb digestion, some persons being intolerant

1 Thin, Brit. Med. Jour., May 4, 1901, p. 1074; D. W. Montgomery, Med. Record,

April 19, 1902 (spontaneous; 6 cases); Hallopeau, Annales, 1903, p. 32; Dyer, Med.

News, July 29, 1905.

2 As especially bearing upon the control in our own country see papers by J. C.

White, “The Contagiousness and Control of Leprosy,” Boston Med. and Surg. Jour.,

Oct. 25, 1894, and Morrow, “Prophylaxis and Control of Leprosy in this Country,”

Trans. Amer. Derm. Assoc. for 1909; and Dyer, “The Sociological Aspects of Leprosy

and the Question of Segregation,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1911, p. 268, and discussion

(Brinckerhoff, C. J. White, Schamberg, Pusey, Morrow, and G. H. Fox), ibid., p. 282.

3 See papers and discussions in Trans. Internat. Leprosy Conference for full details

of the claims and experimental trials of the various special remedies.

936 NEW GROWTHS

even of small quantities. As less irritating to the stomach, the active

principle of the oil, gynocardic acid, has been also commended, usually

in the form of magnesium or sodium gynocardate, in the beginning dose

of ½ grain (0.033), and increasing gradually to 3 grains (0.2) three times

daily. Unna1 makes a soap of the oil with soda, and gives this coated

in pill form, and states that, according to his observations so far made,

in this method of administration there is no disturbing influence on di

gestion. Conjointly with the internal administration it can also be

prescribed by inunction. For this purpose it is mixed with 5 to 15 parts

of olive or cocoanut oil, or as a 50 per cent, ointment with lard. It is to

be rubbed in thoroughly, and, when possible, one to two hours daily.

Before each fresh application the skin is washed with soap and water

or by means of a warm bath.2 Under the favorable influence of this drug

the various disease manifestations abate, sometimes slightly, in others,

but relatively few, quite decidedly, and exceptionally the malady is

halted in its progress.

Gurjun oil (gurjun balsam, wood-oil, from the Dipterocarpus tur-

binatus) has had the warm support of Dougall, Hillis, and some others.

It is usually administered in emulsion, composed of 3 to 5 parts of lime-

water to 1 of the oil, and of which the dose is 2 to 4 drams (8.-16.) two

or three times daily. It is also usually to be conjointly prescribed by

inunction, with 1 to 3 parts of lime-water or olive oil, and thoroughly

rubbed in one to two hours daily. Strychnin, or nux vomica (formerly

as Hoàng nàn, powdered bark of Strychnos gaultheriana), is another

remedy which has had considerable reputation. It is frequently pre

scribed with one of the above oils. Piffard and G. H. Fox, of our own

country, observed in one or two instances practical recovery under their

conjoint use. Morrow also speaks well of the action of this drug. These

three remedies, together with others which may be demanded by general

indications, supported by hygienic measures, frequent baths, good food,

open-air life, and, when possible, change of climate, will often accomplish

much toward at least retarding the progress of the malady.

Many other remedies or plans of treatment have been variously

tried or advocated, more especially in recent years. Unna has spoken

well of ichthyol internally conjointly with external applications of re

ducing agents, to be again referred to. Sodium salicylate and salol

have also had favorable mention, and arsenic has long been considered

of possible value. Although mercury has been more or less considered

as detrimental in the disease, lately Haslund and Crocker have reported

markedly beneficial influence in several instances, the drug being ad

ministered by hypodermic injection deeply into the muscular tissue.

Crocker employed the perchlorid of mercury, using ¼ grain (0.016) in

20 minims (1.33) of distilled water twice weekly. Carreau, and also

Dyer, believe that good effects are sometimes obtainable by increasing

doses of potassium chlorate, an observation previously made by Chis-

1 Unna, Monatschefte, 1900, vol. xxx, p. 139.

2 Tourtoulin Bey, Monatshefte, 1905, vol. xl, p. 88, commends the administration of

the oil by subcutaneous injections, preferably into the subcutaneous tissues of the fore

arm or leg—dosage, 75 minims (5.).

LEPRA 937

holm. Montesant1 and Wellman2 have reported favorable influence

from salvarsan intravenously administered. Wilkinson3 reports a few

apparent cures from x-ray treatment. In recent years various attempts

have been made with treatment with serum (Carrasquilla), antivenene,

or attenuated snake poison (Calmette, Dyer, Woodson), tuberculin

(Yamamoto), and various vaccines—leprolin, nastin, etc (Rost, Deycke,

Rost and Williams, Wise, Minnett, Gottheil, Whitmore, Clegg, Duval

and Gurd, and others), but while at times favorable influences were

noted, the results have been, as a whole, as yet disappointing.4

The external treatment consists essentially in the maintenance of

cleanliness and an aseptic condition of the general surface, in order, so

far as possible, to avoid the suppurative complications due to infection

by pyogenic cocci. Frequent baths, the use of boric acid, formalin,

carbolic acid, and resorcin lotions, and sometimes sulphur baths, are

some of the measures to this end. Certain remedies have, however,

been employed with alleged special influence, such as Chaulmoogra

and gurjun oils, already mentioned, the inunctions of which, in addition,

however, have in view absorption and some constitutional action.

Cashew-nut oil has been similarly employed, both externally and inter

nally. In the opinion of some the good effects of these oils externally

1Montesant, München. Med. Wochenschr., 1910, No. 9, and 1911, No. 11.

2 Wellman, Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, Nov. 16, 1912.

3 Wilkinson, “Leprosy in the Philippines with an Account of its Treatment with

the X-rays,” Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, Feb. 3, 1906.

4 “Carrasquilla Serum,” discussion, Trans. Internat. Leprosy Congress, Berlin, 1897.

“Antivenene,” Dyer, ibid., vol. iii, p. 500, and New Orleans Med. and Surg. Jour.,

Oct., 1897, and Woodson, Philada. Med. Jour., Dec 23, 1899.

“Tuberculin,” latest report by Yamamoto, Japanische Zeitschr. f. Dermalologie und

Urol., Aug., 1912—abs. in Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1912,p. 739—treated a series of 30 cases

with old tuberculin, with alleged remarkable improvement in many.

“Leprolin,” Rost, Indian Med. Gaz., May, June, and Dec, 1904, made from the

culture of the bacillus; Rutherford, Indian Med. Gaz., Feb. 1913, p. 61, 32 cases treated

with leprolin, 20 followed throughout, questionable results, while taking it more deteri

orated than improved.

“Nastin, B.” Deycke, Lepra, 1907, p. 174, made from culture of a streptothrix

found by him in a nodular leprosy, from which he extracted a neutral fat which he called

nastin; this he combined with benzol chlorid in oily solution and called it nastin B.;

this latter is usually employed, nastin sometimes giving rise to alarming reaction;

Brinckerhoff and Wayson, “Studies in Leprosy, U. S. Gov. Printing Office,” 1909—6

cases, disappointing; Wise, Jour. London, Trop. School of Med., 1911, p. 63,—abs. in

Brit. Jour. Derm., 1912, p. 82—in 118 cases of various degrees “nastin” treatment

seemed only successful in 3 cases, the results approximating recovery; 70 patients were

placed on an injection of benzol chlorid in mineral oil (the nastin process without

the nastin), and the results as a whole were rather better than with the nastin; Wise

and Minnett, Jour. Trop. Med., Sept. 2, 1912, p. 259, summary of 244 cases treated

with nastin, at first thought to be encouraging, but proved at the most only a slight

temporary check; Gottheil, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1911, p. 239, 1 case, some improvement.

Editorial review, Indian Med. Gaz., Feb., 1913, p. 71, regarding nastin treatment, by

Harris, Megraw, and Barnardo, states action doubtful.

Other vaccines: Whitmore and Clegg, Philippine Jour. Sci., Dec, 1910, p. 559,

treatment with glycerin extract and soap solution made from vaccine which Clegg had

cultivated from an acid-fast bacillus from the spleen and from the nodules from a num

ber of leprosy cases—results negative; nastin B. in 17 cases negative; Rost, Indian

Med. Gaz., July, 1911, vaccine prepared from cultivation of the leprosy streptothrix,

reports 5 of 12 cases treated as symptomatically cured—injected weekly 1 c.c. of a 1:

400 dilution of dried culture or the equivalent thereof and 1 c.c. of a sterilized six weeks

broth culture; Rost and Williams (loc. cit.), vaccine prepared from a culture of leper

bacillus in a medium consisting of distilled volatile alkaloid of rotten fish, lenco broth

(without salt or peptone), and milk; obtained hopeful results.

938 NEW GROWTHS

used lie, in great part, in the associated prolonged rubbing. Unna has

strongly commended, along with the internal administration of ichthyol,

the local applications of ointments containing the reducing agents,

resorcin, pyrogallol, chrysarobin, salicylic acid, and also ichthyol; a

compound formula recently advised by him, consisting of salicylic acid,

2 parts; ichthyol and chrysarobin, each, 5 parts; vaselin, 100 parts.

To limited areas the pyrogallol can be added in the same quantity as the

chrysarobin, or can be substituted for the latter. In some instances

excision and curetting of the nodules and infiltrations have been practised,

but the results are scarcely such to justify such heroic measures. Ulcera-

tions should be kept thoroughly cleansed, and, so far as possible, aseptic,

by the use of hydrogen dioxid washings, weak corrosive sublimate solu

tions, boric acid lotions, and similar applications. As ointments for apply

ing to open lesions may be mentioned those containing aristol, resorcin,

salicylic acid, ichthyol, balsam of Peru, and the like. Robertson1 com

mends applications of formalin, using it diluted to open wounds and pure

to other lesions. For the relief of the painful neuralgias, sometimes

of severe character, Rake and others have reported good results from

nerve-stretching. Electricity has been employed with some benefit

to anesthetic areas.

1 Robertson, Jour. Trop. Med., 1904, p. 26.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |