| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

SCLERODERMA1

Synonyms.—Hidebound skin; Sclerema; Scleriasis; Sclerema adultorum; Derma-

tosclerosis; Fr., Sclérodermie; Sclérème des adultes; Ger., Sklerodermie.

Definition.—A chronic disease, characterized by a circumscribed

localized, or general and more or less diffuse, usually pigmented, rigid,

stiffened, indurated, or hidebound condition of the skin.

The manifestation differs materially in extent and character, in

some cases being more or less diffused, hard, hidebound, and with usually

considerable pigmentation, and in others consisting of rather sharply

circumscribed patches or bands of a somewhat lardaceous appearance,

and often, especially the rounded areas, with a pinkish border. The

former is the variety usually known as diffuse symmetric scleroderma;

the latter, as circumscribed scleroderma or morphea. Duhring main

tains that morphea is distinct from scleroderma, and it must be confessed

that the extremes of these two types bear practically no clinical resem

blance, one to the other, but other cases approach more closely and merge

into each other, some cases presenting the typical conditions of both.

1 Some valuable recent literature: Lewin and Heller, Die Sklerodermie, Berlin, 1895

(a review of the entire subject, embracing 508 collected cases); Osier, Jour. Cutan. Dis.,

1898. pp. 49 and 127 (a report of 8 cases of diffuse scleroderma, with review comments

on the disease, especially diagnosis and treatment with thyroid extract); Dercum, Jour,

of Nervous and Mental Dis., July, 1896 (3 cases) and (on scleroderma and rheumatoid

arthritis—with reports of 2 cases), ibid., October, 1898; Méneau, Jour. mal. cutan., 1898,

p. 145; Colcott Fox, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1892, p. 101, also contributes an interesting

historic paper bearing upon early observations of English observers on the disease.

SCLERODERMA

579

Symptoms.—The diffuse type may begin insidiously or rapidly.

In the former event the first symptom noted is a slight stiffness of the

part involved, which may at first be extremely limited. On examina

tion, variable swelling or infiltration is usually noted, the surface is some

what tense looking, and sometimes shining; at other times there is noted,

along with the first symptoms, more or less yellowish-brown or brownish

pigmentation, and which may, indeed, be the first manifestation ob

served by the patient. As a rule, there are no subjective symptoms

complained of in the early stages, except in some cases occasional neural

gic or rheumatic pains. The division between the affected and the

healthy skin is not well defined, one insensibly disappearing into the other.

Fig. 140.—Scleroderma—band or ribbon type, extending full length of the arm.

Several “morphea” patches on back.

The process gradually extends, and, after the course of weeks or some

months or several years, finally involves one or more regions or the

greater part of the entire surface. It may be limited to the arms or the

lower extremities, extending sometimes on to the trunk; or the face,

neck, and immediately adjacent parts are the seat of the induration.

When well established the integument is brawny or leathery, hard to the

touch, stiff, rigid, and cannot be lifted up into folds. It is usually appar

ently agglutinated with the subjacent tissues, and the entire part is more

or less immobile.

In the rapidly spreading or acute type, the process is commonly

ushered in by more or less edematous infiltration, with or without

580 HYPERTROPHIES

preceding chills, fever, or other constitutional disturbance. The tissues

and skin are tense and generally glossy, and in some instances may pit

slightly upon pressure, although, as a rule, owing to the tenseness and

beginning hardening, this is not readily produced. In these edematous

or infiltrating cases the skin is often whitish or waxy, somewhat similar

to the appearances observed in ordinary edema. The disease rapidly

extends, and soon a greater part of the entire surface is invaded. The

infiltration or edema disappears as the integument becomes hard and

rigid, and practically the same picture is presented as in the insidious

form: the skin is dry, sometimes harsh, sometimes smooth, hide

bound, stiff, and hard and more or less pigmented, and not infre

quently with some shriveled epidermic scaliness. In some instances,

in places, especially the lower leg, there is slight wart-like papillary

hypertrophy.

If the limbs are involved, they are stiff and immobile, and later

become shrunken and withered, the underlying muscles also atrophying,

and the whole region—skin, tissue, muscle, and bone—seems glued

together and atrophic. In some cases (Thibiérge)1 the muscles are

noted to be atrophic, even where there is no overlying sclerodermic

areas. If the face is the part involved, the countenance is immobile,

expressionless, the wrinkles and lines obliterated, and the mouth slightly

or firmly rigid. In fact, the integument has a wooden or petrified look.

Atrophic changes may take place here also, but not so commonly as with

the extremities. When seriously involving the latter, joint symptoms

of an arthritic or rheumatoid arthritic character are noted, and, in addi

tion to the enormous shrinking and atrophy which sometimes ensue, even

to the extent of reducing the arm of an adult to almost that of a child,

the joints become ankylosed, the fingers bent and fixed, resulting in a

veritable sclerodactylia, an associated condition to which Ball called

attention, and well shown in cases more recently reported by Osier,2

Dercum.3 Elliot,4 Uhlenhuth,5 and others.6 Both the fingers and toes

may be the seat of these changes, as in some of the cases just referred to

and in one referred to by Kalischer.7 Sometimes such distortion is

preceded by pain, occasionally cyanosis, and, in fact, many of the other

symptoms of Raynaud‘s disease (Bouttier, Chauffard, and others).8

Ulcerations are apt to form over the knuckle prominences, and the whole

condition be a painful and troublesome one. In such cases and in

others often the first troublesome symptom noted is slight ulceration

1 Thibiérge, “Contribution a l‘étude des lésions musculaire dans la sclérodermie,”

Revue de Méd., 1890, p. 291, calls special attention to the characters of the muscular

atrophy observed and refers to other literature cases; Bloch, Berlin, klin. Wochenschr.,

1899, P- 307, has added a case of bone and muscle atrophy to those already reported;

also case reported by Adler, ibid.; and one by Nixon, Bristol Medico-Chirurg. Jour.,

Dec, 1903, and refers to case by Dreschfeld (Manchester Med. Chronicle, 1897, p. 263).

2 Osier, loc. cit. 3 Dercum, loc. cit.

4 Elliot, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1899, P- 575-

5 Uhlenhuth, Berlin klin. Wochenschr., 1899, p. 207.

6 Gordonier, Amer. Jour. Med. Sci., 1889, vol. xcvii, p. 15, reports a case and re

views others.

7 Kalischer, Wien. med. Rundschau, 1899, p. 65.

8 Bouttier, “De la Sclérodermie,” These de Paris, 1886; Chauffard, abs.-ref.,

Annales, 1897, p. 895; also noted by Osier, Dercum, and others.

SCLERODERMA

58l

of the finger-ends; Jacoby‘s1 case began in the form of open sores,

the different finger-tips being successively attacked, and Eichhoff2

observed an instance somewhat similar, but in which the apparent

exciting factor of the atrophic and destructive process was a favus

of the nails. In some cases, especially those in which the subcutaneous

tissues and muscles have atrophied, the hardened skin may tend to ulcer

ate over sharp bony prominences.

The disease may, however, begin on any region, and the most fre

quent one is that of the neck, although shoulders, back, chest, arms, and

face are not uncommon sites. It may limit itself somewhat, or it may

gradually or quickly involve almost the entire surface. As a rule, it is

extensive. It may be somewhat irregular in its distribution, but it is

usually symmetric—in a case described by Britton,3 the disease was not

only diffused over most of the surface, but its symmetric character was

perfect; and in one recently noted by Bruns,4 the disease involved both

lower extremities, extending upward and stopping short level with the

second sacral vertebra. Not only may the skin be involved more or less

extensively, but the mucous membrane of the mouth as well, and this

has also been observed even when the integumentary involvement was

limited. Sometimes, too, the teeth loosen and fall out (Dercum). In

some cases the scleroderma presents in wide strips or bands, and occa

sionally associated with circumscribed areas of more or less typical

morphea, and in exceptional instances, in addition to the sclerodermic

changes, there are noted associated alopecia and leukoderma.5

As a rule, there are no distinctive or special constitutional symptoms

in scleroderma; some of the less extensive cases and most of those of

wide distribution are ushered in by chills, fever, and other evidences

of general disturbance. There are not infrequently, however, concomit

ant or developing rheumatic symptoms and occasionally those of rheu

matoid arthritis. Pigmentation is sometimes marked, and sometimes

suggestive of Addison‘s disease; in exceptional instances this latter has

been reported to coexist. Local pain, occasionally cramp-like in char

acter, heat or burning, and a sense of numbness, and, as already referred

to, edema are sometimes precursory and early accompanying symptoms.

The sweat secretion of the involved region is diminished, and usually

entirely suppressed. Sensibility of the parts is rarely affected, but there

is itching in some cases. Changes in the thyroid gland have also been

observed in some instances (Singer, Jeanselme, Ditscheim, Grünfeld,

Osier, Uhlenhuth, James, Samouilson, and others), but usually in asso

ciation with coexistent Graves’ disease. In extreme types, especially

when the face is involved, from stiffening and often contraction of

the mouth, proper nourishment is interfered with, and the patient

suffers from inanition. From hardening and contraction of the

1 Jacoby, Philada. Med. Jour., April 15, 1899.

2 Eichhofl, Archiv, 1890, vol. xxii, p. 857 (with cut).

3 Britton, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1891, p. 227.

4 Bruns, Deutsche med. Wochenschr., 1899, p. 487.

5 Eddowes, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1899, p. 325, exhibited before Derm. Soc‘y of Great

Britain and Ireland a case presenting general alopecia, leukoderma, scleroderma, and

morphea patches.

582 HYPERTROPHIES

integument of the chest breathing is also seriously interfered with in

some cases.

The course of the disease is essentially chronic, sometimes exten

sion being slow, at other times rapid. In some cases there is occa

sional retrogression, which may even go on to complete recovery, but

before such a fortunate conclusion there may occur one or more exacer

bations, usually foreshadowed by chilliness or chills and other systemic

disturbance.1 The edematous cases are more likely to lead to atrophic

changes—Crocker believes this to be the result in all of them.

Circumscribed Scleroderma—Morphea (known formerly as Keloid

of Addison).—The disease may present some variations. The typical

examples, those which seem wholly different from scleroderma, begin,

as a rule, by the appearance of light-pinkish or hyperemic, usually oval

or rounded, small coin-sized patches. There may be slight elevation

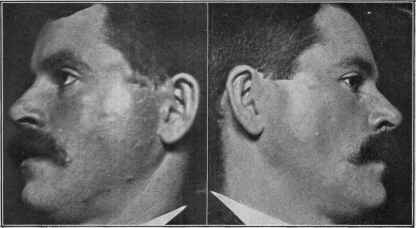

Fig. 141.—Circumscribed scleroderma (morphea) in a man aged thirty; consisting

of two symmetric areas shown, which were waxy or lardaceous in appearance, quite

firm to the touch, and with a slight peripheral, pinkish border, although this was not at

all marked and discernible only upon close inspection. Duration one year and of

gradual appearance.

or an appearance of scarcely perceptible puffiness. The color, in the

course of some days—a variable time—fades out, and the patch is ob

served to be encircled with a faint rosy or pinkish zone, which, on close

examination, is found to be made up of minute capillaries, while the area

itself is whitish or ivory-like, or lardaceous, and seems inlaid in the skin.

It is usually on a level with the surface, or it may be slightly depressed;

it often has a polished look, and it is either somewhat soft to the touch,

and when pinched up not materially different from the surrounding

skin, or it is noted to be firm, hard, leathery, and even brawny. On

close inspection very often the surface is observed to be coursed over by

1 An interesting paper and review in this connection: Kanoky and Sutton, “A Com

parative Study of Acrodermatitis Chronica Atrophicans and Diffuse Scleroderma, with

Associated Morphea Atrophica,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., Dec, 1909 (illustrated, bibliog

raphy).

SCLERODERMA

583

minute blood-vessels, sometimes forming a faint network. Later,

instead of a smooth, shining surface, there may be slight, thin, shriveled

epidermic coating. Beyond the faint pinkish, or sometimes lilac-

colored, border, a slight yellowish or yellowish-brown, often mottled,

irregularly diffused pigmentation is noticeable, which may extend some

distance from the patch.

Fig. 142.—Circumscribed scleroderma (morphea) in a middle-aged working-

woman; disease limited to the patch shown on the leg. Duration about one year. The

pinkish or lilac border present in most cases is shown by the dark peripheral shading.

The inclosed area is whitened and lardaceous in appearance. The two small ulcera-

tions are accidental, due to traumatism.

In some instances the patches, instead of being pinkish or rosy,

begin as whitish or bluish-white (Handford1) areas, later becoming yel

lowish. In exceptional instances the erythematous stage usually

noticed is prolonged. As a rare example of this latter was one under

Cavafy‘s2 observation, in which the legs were for months the seat of

1 Handford, Illus. Med. News, June 22, 1889, p. 265, records, in a report of 2 cases,

a case of this kind (with colored plate and histologic cut).

2 Cavafy, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1896, p. 275.

584

HYPER TROPHIES

erythematous areas of obscure nature, but which finally began to

harden, the erythema disappearing and giving place to lardaceous

patches. In other instances, instead of the typical characteristic patches,

there appear several or more small or large scar-like spots, sometimes

slightly depressed; the skin is atrophic or thin, and often with neighbor

ing telangiectases of reddish or bluish color. Pigmented areas, true

sclerodermic areas, pit-like atrophic depressions, and atrophic lines are

also present in some cases.1 Or, instead of lesions of these characters,

the disease may present in irregularly rounded areas, or short or long

bands, hard and brownish, sometimes with the peculiar pinkish capillary

border or with abrupt termination in the skin beyond, which may or

may not be pigmented. Occasionally a band extends almost the entire

length of a limb, and may be elevated or countersunk. In these cases

paroxysmal attacks of cramp-like pain are now and then noted.

The course of the typical lesions of morphea is variable—usually

slow and chronic in character; they frequently enlarge slowly, and if

close together, coalescence results, and large areas may be covered.

Very often after reaching the diameter of a few inches they remain

stationary for an indefinite time, either with a gradual tendency to

enlargement or to retrogression and disappearance. In some cases

decided atrophic changes ensue, and the final result is akin to that ob

served in diffuse scleroderma: the skin is shriveled and thin, and some

times hard and fibrous, the tissues beneath gradually atrophy, and the

parts agglutinated together, finally forming irregular, smooth or fur

rowed, sunken, contracted scars, sometimes of keloidal aspect or nature.

In rare instances ulceration takes place, usually in parts of the involved

area only.

Morphea patches may develop upon any region, but its most com

mon sites are the upper trunk, face, neck, abdomen, and the arms and

thighs; as a rule, but several areas are seen, but it may be widespread

over several regions, as in extensive cases described by Morrow2 and

Cavafy,3 in which there were numerous large areas from the hips down

on both legs, and with more or less perfect symmetry. Ordinarily patches

of the disease are irregularly distributed, sometimes presenting on but

a single region; occasionally the distribution corresponds to that of the

cutaneous nerves, and exceptionally the manifestation has been strictly

limited to the fifth nerve, as in Anderson‘s4 case, in which the entire

region of the distribution of the three divisions of the right fifth nerve

was the seat of sclerodermic changes, including the mucous membrane

of the mouth and the upper part of the pharynx. Barrs5 observed a

case in which the disease, upon both arms and left leg, followed very

accurately the nerve-fields.

In rare instances, closely analogous to the last, as in a case also

1 Duhring, Amer. Jour. Med. Sci., Nov., 1892, reports an interesting case of asso

ciated morphea patches and atrophic lines and spots.

2 Morrow, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1896, p. 419 (with 3 illustrations) and discussion

(White and Duhring), p. 446.

3 Cavafy, loc. cit.

4 W, Anderson, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1898, p. 46.

5Barrs, ibid., 1891, p. 152.

SCLERODERMA

585

reported by this last observer (Barrs), as well as by others previously,

the disease seems to limit itself, chiefly at least, to one side of the face

(hemiatrophia facialis or unilateral atrophy of the face), but not infre

quently with one or several characteristic patches elsewhere. With

these cases, however, the atrophic “shrinking” influence of the disease

is especially noticeable, not only the skin, but the subcutaneous tissue

muscles, and even the bones becoming involved, and great deformity

sometimes resulting.

Etiology.—Both types of scleroderma are infrequent—the dif

fused type rare, the circumscribed variety—morphea—much less so.

It is met with in both sexes, but with a considerable preponderance

on the female side, and this, I believe, is even more pronounced in

morphea. In Lewin and Heller‘s statistics, out of 435 cases, 292 were

females. It is chiefly observed in those between the ages of fifteen

and forty-five, but no age except early infancy is exempt, as it has been

met with both in the very young (the youngest patient recorded being

thirteen months old) and the very old. Various causes have been as

signed, but there remains much to be learned before anything definite

can be stated on this score. Rheumatism, chills, exposure to cold and

wet, prolonged sun-exposure, thyroid disease, exhaustion from any cause,

emotional and other nervous disturbances, filaria sanguinis (Bancroft),

arterial disease, and many other factors are named as of etiologic in

fluence. Some cases have apparently had their start in some local

irritation or injury, another example of which is recently recorded by

Leslie Roberts.1 In some instances, however, the patients at the time

of the attack are apparently in good health, and when the involvement

is not unusually extensive, the general condition may remain compara

tively undisturbed; this is especially so in most cases of morphea.

Zambaco2 is inclined to view the disease as an anomalous or modified

form of leprosy.

The rheumatic origin of the disease has the frequent occurrence

of rheumatic and rheumatoid arthritic symptoms to support it, such

symptoms sometimes antedating the sclerodermic changes, and in other

cases being concurrent. These facts are, however, in my judgment,

more especially as to rheumatoid arthritis, merely an added evidence

in favor of the neurotic cause of the disease, which, upon the whole,

has the greatest support. That changes in the thyroid gland are noted

in some cases has already been remarked upon, usually, however, in

association with Graves’ disease, but also in some instances in which

this latter did not exist, usually atrophic in character, as reported by

several observers, more recently by Hektoen,3 Uhlenhuth,4 James,5 and

others.6

1 Roberts, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1900, p. 118.

2 Zambaco, Trans. First Internat. Leprosy Congress.

3 Hektoen, Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, June 26, 1897, vol. xxviii, p. 1240.

4 Uhlenhuth, Berlin klin. Wochenschr., 1899, p. 207.

5 James, Scottish Med. and Surg. Jour., May, 1899.

6 Samouilson, “De la Coéxistence de la sclérodermie et des altérations des corps

thyroide,” These de Paris, July 21, 1898, considers the subject at length and reviews

the literature, with the conclusion that the disease is sometimes due to an intoxication

resulting from abnormal action of the thyroid gland; Leven, Dermatolog, Centralblatt,

586 HYPERTROPHIES

In favor of its being a neurosis are the occasional nerve distribu

tion, its frequent symmetric arrangement, the occasional preceding or

concurrent finger symptoms, suggesting Raynaud‘s disease, the occasional

local sensory symptoms, the sometimes noted coexistence of alopecia

and leukoderma, the pigmentary changes, the muscle and bone atrophy,

etc.

Pathology.—Knowing so little regarding the essential causes

which provoke the disease, it is difficult to formulate a satisfactory

explanation of the pathologic changes which take place in the cutaneous

structures. As Osier succinctly states, as already in part intimated in

etiology, the disease is variously regarded as a trophoneurosis dependent

upon changes in the nervous system—a perversion of nutrition analogous

to myxedema, and due to disturbance of the thyroid function; a sclerosis

following widespread endarteritis; a primary slow hyperplasia of the

collagenous intercellular substance of the corium—fibromatosis; or a

primary affection of the lymph-channels, central or peripheral. Lewin

and Heller, from their valuable studies, are led to view the disease as a

neurosis—an angioneurosis, trophoneurosis, or angiotrophoneurosis. As

Crocker states, most of the symptoms can be referred to obstruction,—

arterial, lymph, and venous,—and that the variable character of changes

observed in different cases depends upon which of the vascular sys

tems is most involved. According to Unna, the first changes are in

the connective tissue, especially its intercellular substance. It is

probable that the primary pathogenic influence is to be found in the

central nervous system, although many (Chiari, Spieler, Dinkier, and

others) have failed to find such evidence; but, on the other hand, West-

phal,1 Jacquet and de Saint-Germain,2 Schulz,3 and Steven4 have noted

degenerative and sclerotic changes in the brain, spinal cord, or sympa

thetic, but there was no uniformity, and the exact relationship cannot,

therefore, be definitely stated. Brissaud5 believes it takes its origin in

some disturbance of the sympathetic. In Schulz‘s case, in which there

was considerable general pigmentation, one suprarenal body was found

somewhat diseased.

The anatomic changes observed in the diffuse type (Neumann,

Kaposi, Auspitz, Schwimmer, Fagge, and others) are essentially in the

corium and subcutaneous tissues. Pigmentation, it is true, is found in

the rete, and not infrequently in the corium also, especially in the papil-

Feb., 1904 (associated development of thyroid); Roques, “Le Traitement opothéra-

pique de la sclerodermie,” Annales, July 1910, p. 383, reviewing the subject, found

a larger proportion with defective thyroids; full review of literature; bibliography;

Alderson, “The Skin as Influenced by the Thyroid Gland,” California State Jour, of

Med., June, 1911, (gives a brief, but good review of recorded thyroid gland influences).

1 Westphal (2 cases—1 autopsy), Charité-Annalen, Berlin, 1876, vol. iii, p. 341.

2 Jacquet and de Saint-Germain, Annales, 1892, p. 508.

3 Schulz, “Sclerodermie, Morbus Addisonii und Muskelatrophie,,, Neurologisches

Centralblatt, 1889, pp. 345, 386, and 412, with references.

4 Steven, Glasgow Med. Jour., Dec 1898; editorial review of same in Lancet, 1899,

vol. i, p. 43; clinical account of case in Internat. Clinics, July, 1897, vol. ii, p. 195,

with 4 illustrations (an interesting case leading to pronounced hemiatrophy of the face,

body, and extremities, with deformity and fibrous ankylosis of the joints).

5 Brissaud, La Presse médicate, 1897, p. 285—full abstract in Brit. Jour. Derm.,

1897, p. 367—reviews the various theories (with many references).

SCLERODERMA

587

lary layer. Both in the true skin and subcutaneous connective tissue

there is a marked increase of connective-tissue element, with thickening

and condensation. The fat atrophies and gives place to connective

tissue. The vessels are found surrounded by masses of small cells of

unknown origin, and are thereby diminished in caliber; the latter is also

due to thickening of the media and intima. The glandular structures

are irregularly surrounded by these cell-masses, but are primarily other

wise unchanged; in the later stages, however, they are atrophied. Ex

cepting the presence of these cells there are no inflammatory signs.

The papillae are usually normal in size, although in some cases in which a

papillomatous tendency is noted hypertrophy is observed. The con

nective tissue and elastic tissue of the corium are increased, densely

packed, and the entire cutaneous structure is converted into a dense

mass. The histologic changes in the circumscribed form, studied

carefully by Crocker, vary relatively little from those of the diffused

type in its early stage, both having the same anatomic basis, the cell

exudation bringing about the first change—narrowing of the vessels,

fibrillar tissue formation, and atrophic changes; the pinkish or violaceous

zone is due to collateral hyperemia around an anemic area. Duhring

found in a soft, pliable, whitish patch of some months’ duration a con

densation of the connective tissue of the corium, with a shrinkage of the

papillary layer.

Diagnosis.—In well-marked cases of diffused scleroderma the

characters—rigidity, stiffness, hardness, and hidebound condition of

the skin, with usually more or less pigmentation—are quite distinctive

and scarcely admit of error. In the less marked and obscure examples

possible confusion might occur with Raynaud‘s disease, the brawny

induration sometimes observed in scorbutus, myxedema, and leprosy,

but the features and mode of onset of these several affections are clearly

different. The nervous phenomena, the usually preceding and long-

continued and often periodic stasic and anemic conditions of the favorite

limited regions in Raynaud‘s disease, are differential points of value,

and together with the absence of any tendency to extensive hardening

or thickening will usually serve to prevent a mistake in this direction.

The localization of the brawny hardness of scurvy, the purpuric element,

and other symptoms are distinct from those of scleroderma. The

edematous stage observed in some cases presents a similarity to myx-

edema, but the distribution and mode of onset of the latter, the absence

of sclerotic and other features, are different. Leprosy can scarcely be

confounded with diffuse scleroderma, the sensory disturbances usually

present and often preceding the development of the cutaneous symptoms

in the former, the absence of tendency to brawny hardening, the history

of the case, and the exposure to the disease are points to be considered.

The malady can scarcely be mistaken for xeroderma pigmentosum.

Sclerema neonatorum, a somewhat allied disease, is an affection of

earliest infancy, whereas scleroderma has never been noted before the

second year of life.

The early white plaques of morphea—circumscribed scleroderma—

in some cases resemble closely similar areas not infrequently seen in

588

HYPERTROPHIES

leprosy, but the symptoms and characters of the latter already noted are

of different nature. The morpheic white areas may also bear resem

blance to vitiligo, but in the latter the sole essential symptom is loss of

pigment—no thickening or other change in the skin. In women a mis

take between carcinomatous skin invasion of the breast (cancer en

cuirasse) and the circumscribed sclerodermic disease has been made, but

careful investigation should prevent error.

Prognosis.—The outcome in a given case of either variety as

regards cure is uncertain; the diffused type is often fatal, usually from

some intercurrent affection superinduced by the patient‘s condition.

In those in which the chest is practically incased in an unyielding armor,

and the mouth narrowed and fixed, and the jaws firm, interfering with

respiration and nutrition, the prospect is unfavorable. According to

Méneau, the scleroderma, progressive in character, beginning at the

extremities and spreading to other parts, is generally fatal. On the other

hand, in many extensive cases and seemingly unfavorable, if decided

atrophic changes have not occurred, recovery takes place.

The circumscribed form—morphea—is a relatively mild affection,

often persisting, it is true, and in some cases, almost indefinitely, but is

not necessarily dangerous, and very often, after some months or a year

or two, either as the result of treatment and sometimes spontaneously,

complete recovery ensues. Considerable deformity may, however,

result in the rarer instances in which atrophy takes place.

Treatment.—The patient‘s general health must receive proper

attention, and such tonics as quinin, strychnin, iron, arsenic, sodium

salicylate, and cod-liver oil have an important influence in some cases.

Of these, several—arsenic, sodium salicylate, and cod-liver oil—have in

my experience been the most valuable, and probably possess more than

a simple tonic and alterative value. My own observations, however,

have concerned, for the most part, the circumscribed forms of the disease.

In extensive cases, in addition to those remedies named, the adminis

tration of pilocarpin, properly supported with stimulants and tonics,

and its action on the sweat-glands promoted by warm clothing or bed-

covering, is of some value when the sweat secretion is markedly in

abeyance. Recently thyroid extract has been advocated, but the re

ports are at variance. Osier has not been favorably impressed with its

use, although still recommending its trial. The cases mentioned by

Lewin and Heller, in which this treatment was adopted, were not ma

terially influenced, and this was also the experience of Uhlenhuth,

Dreschfeld,1 and some others. On the other hand, Marsh,2 Lustgarten,3

Gayet,4 Eddowes,5 Roques,6 and others have seen betterment take place.

As yet, therefore, the exact value of this remedy remains to be deter

mined—it should, however, be tried, in all diffused cases at least.

The local treatment most efficacious consists essentially in the use

1 Dreschfeld, Medical Chronicle, 1896-97, vol. vi, p. 263.

2 Marsh, Med. News, 1895, vol. lxvi, p. 427.

3 Lustgarten, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1895, p. 27 (brief reference only).

4 Gayet, Jour. mal. cutan., Jan., 1900.

5 Eddowes, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1899, p. 325.

6 Roques, loc. cit.

SCLEREMA NEONATORITM

589

of friction with oils or ointments and massage. The applications should

usually be of mild character, or in limited, obstinate, non-irritable areas,

quite stimulating. As a mild ointment may be mentioned one contain

ing salicylic acid 10 grains (0.65), cacao-butter 2 drams (8.), lanolin

2 drams (8.), petrolatum 4 drams (16.); or 1 or 2 per cent, salicylated

oil can be used. In the hard, thickened, sclerodermic areas in the cir

cumscribed form I have used with advantage an oil consisting of 1 or

2 parts of oil of turpentine with 6 parts oil of sweet almonds; and an oint

ment of 2 parts oil of turpentine, 1 part beta-naphthol, 2 parts oil of

sweet almonds, and 10 parts lanolin; and in the tough band areas on the

extremities, sometimes associated with paroxysmal pain, an ointment

containing 5 or 10 grains (0.35-0.65) of menthol and \ dram (2.) of chloro

form to the ounce.

In the typical soft or moderately hard areas of morphea, especially

in the earliest stages, the mild applications are to be used, the stronger

sometimes tending to produce irritation. Electric treatment, consist

ing of general and local galvanization, has been commended by some

observers; with the former I have had no experience, but the latter,

using a current of 2 to 10 milliampères, with friction movements of the

two electrodes—labile application—has seemed to me of some advantage;

likewise the use of the static battery roller electrodes made over the part,

while covered with the clothing or some fabric. In the past few years

favorable statements have been made of electrolysis in the treatment of

circumscribed patches by Brocq,1 Darier and Gaston,2 and Allen.3

I have had no experience with this method. It is employed in the same

manner as in the removal of superfluous hairs: current strength between

½ to 10 milliampères, according to sensitiveness of the patient and the

integumentary conditions; the stronger current in the more infiltrated

areas, if the patient bears it, and in such cases, too, the duration of the

application somewhat longer than in the softer and less infiltrated patches.

Brocq employs as supplementary to the electrolytic procedure the ap

plication of mercurial plaster, which, I believe, should have a share in

the credit for the good results claimed by him. X-ray treatment is some

times especially valuable in the morphea type of the disease.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |