| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

CHLOASMA

Synonyms.—Moth patches or spots; Liver spots; Fr., Chloasme; Panne hépatique;

Tache hépatique; Chaleur du foie; Ger., Pigmentflecken; Leberflecken.

Definition.—Chloasma is the term applied to increased pigmen

tation of the skin, occurring as variously sized and shaped, yellowish,

brownish, or blackish patches, or as more or less diffused discoloration.

Symptoms.—More commonly chloasma appears as ill-defined,

somewhat rounded patches; less frequently as a diffuse discoloration.

Its appearance is rapid or slow, although usually insidious and gradual,

and unattended by any subjective symptoms, the sole symptom con

sisting in the deposit of more or less additional pigment, without textural

change. There is, therefore, no elevation, and the surface of the skin

remains smooth, although in some of the localized forms, especially on

the face, there may be a slight coexisting oily seborrhea. The patches

are rarely numerous, one, several, or more being present, and generally

shade off gradually into the surrounding normal skin; sometimes coalesc

ing and forming one or more large irregular and ill-defined areas. The

face is the usual site for the common or patchy variety, although it may

also be found occasionally on the trunk and other parts, but is then, as a

CHLOASMA

505

rule, the result of some external agency. The diffused discoloration may

occupy a portion of the body, or more or less of the entire surface. In

these latter instances the discoloration is always deeper in those parts

which are normally darker, such as about the eyes, neck, axillae, geni-

tocrural region, and about the nipple. The color is yellowish or brown

ish, and may even be blackish; when the last, the malady is more com

monly designated by the practically synonymous term, melasma or

melanoderma. Depending upon the etiologic factors, whether external

or internal, chloasma cases are usually grouped in two classes—idiopathic

and symptomatic.

Idiopathic chloasma (chloasma idiopathicum) includes all those

cases in which the pigmentary increase is due to local or external agents,

such as the sun‘s rays, sinapisms, blisters, continued cutaneous hyper-

emia, or irritation due to pressure, friction, scratching, parasites, and

like causes. The increased discoloration following continued exposure

to the sun or diffused bright light is the result of the action of the chemical

rays, and may also occur in prolonged exposure to strong electric light,

although to a relatively slight extent. The heat itself has also an in

fluence, although a minor action when compared to chemical rays; it

will, however, when long continued and repeated, bring about some in

crease of depth in the skin tint, as observed in those whose occupation

demands close proximity to the fire, as stokers, etc. The chloasma thus

variously produced is sometimes also designated chloasma caloricum.

The first stage, usually, of such is slight erythema or hyperemia. In this

connection the pigmentation resulting from repeated exposure to the

x-ray may also be mentioned, following after erythema, which it often

produces; the discoloration is usually slight, and doubtless the effect

of both the light and the current, although in what manner the latter

is causative, if it is so, is not known. The discoloration resulting from

the application of sinapisms and blisters, and from certain drugs, known

also under the name of chloasma toxicum, is an occasional occurrence,

and sometimes it is quite persistent, as in an instance which came under

my own observation in a young, fashionable woman who had had a

mustard plaster applied over the sternal region, deep pigmentation de

veloping as the redness subsided, and lasting for months as a sharply

defined area, the exact shape and size of the plaster, making the wearing

of décolletté gowns impossible. It remains at the site of the application,

although Dubreuilh1 reports a case in which, apparently as a result of a

mild spreading dermatitis produced, it extended considerably beyond.

The increased discoloration due to pressure and friction, as well as

other traumatic agents (chloasma traumaticum), is exemplified in those

regions against which a truss is in constant contact. To the same cause

is doubtless to be attributed the slight darkening of the skin of the neck

region noticeable in some individuals. Of especial dermatologic interest

is the pigmentation resulting from prolonged hyperemia and irritation,

as that observed in consequence of the scratching induced by chronic

irritation of the skin, particularly in long-continued pruritus, dermatitis

herpetiformis, and pediculosis corporis, as well as other lasting, itchy,

1 Dubreuilh, Annales, 1891, p. 76.

5o6

HYPERTROPHIES

cutaneous diseases constituting the pityriasis nigra of Willan. Syphilitic

eruptions may, as is well known, also leave some pigmentary stain.

In pediculosis it becomes, after long continuance of this malady, often

extremely pronounced—so much so that, exceptionally, there is a strong

suggestion of Addison‘s disease; one such instance came under my notice

at the Philadelphia (Charity) Hospital, the patient having been sent

by the admitting physician to the medical ward under the belief that

it was the latter affection. Similar extreme examples have been reported

by Greenhow.1 In pediculosis the pigmentation is most marked, as is to

be expected, on those situations where the irritation is greatest, as across

the shoulders and upper part of the back, around the waist, over the

sacrum, etc. (see Pediculosis). It is, in moderately marked cases, some

what spotty, with also some small, somewhat whitened, atrophic or

scar-like spots intermingled, the latter the sites where the skin has been

deeply gouged out by the nails in scratching. Other parasites in addition

to lice and the itch-mites can also bring about pigmentation or pseudo-

pigmentary changes, as in a few rare instances from the demodex fol-

liculorum (q. v.) and from the microsporon furfur (see Tinea versicolor),

microsporon minutissimum (see Erythrasma), which will be referred to

in the proper place.

Symptomatic chloasma (chloasma symptomaticum) is the more

important variety, and includes all forms of pigment deposit which occur

as a consequence of various organic and systemic diseases, as the pig

mentation, for example, observed in association with tuberculosis,

secondary syphilis, sarcoma, cancer, malaria, Addison's disease, Graves’

disease, and functional and organic affections of the utero-ovarian sys

tem. With the exception of the pigmentation observed in the last named,

the most common cause of symptomatic chloasma, it is usually more or

less diffused. The hyperpigmentation bordering the white depigmented

patches in vitiligo and that of the pigmentary syphiloderm are consid

ered under these diseases, and need not, therefore, be discussed here.

Moreover, the discoloration of these various cachectic maladies (chloasma

cachecticorum) named is too well known to need special description,

although to the practised eye there is often considerable difference in

depth and shading in the several affections. In tuberculosis, in its

greatest development, it is somewhat on the tint of the color in Addison‘s

disease, although much less pronounced, and sometimes extremely slight.2

The peculiar sallow or earthy color of the early stages of secondary

syphilis, most marked on, and sometimes practically limited to, the face,

is often sufficiently distinct to be of some corroborative value in other

wise doubtful cases. A somewhat similar tint is frequently seen in

sarcoma and also in cancer, but usually with a trifling lemon-yellow

coloring. In malaria there is generally a sallow color, with a brownish

tint, while in morbus Addisoni it is of a somewhat slaty, bronzed hue.

1 Greenhow, “Vagabond‘s Discoloration Simulating the Bronzed Skin of Addison‘s

Disease,” Trans. London Clin. Soc‘y, 1876, vol. ix, p. 44.

2W. G. Smith, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1892, p. 386, describes an extreme case; also

Andrewes, “Two Cases of Tuberculosis with Unusual Pigmentation of the Skin and

Deposit in the Suprarenals,” St. Barthol. Hosp. Rep., 1891, vol. xxvii, p. 109 (with

remarks).

CHLOASMA

5O7

In Graves’ disease there is also sometimes observed a brownish-yellow

pigmentation, either in freckle-like spots, patchy, or, in rarer instances,

as a more or less diffused discoloration, of which examples are cited by

Drummond,1 Mackenzie,2 Nicol,3 and others.

Chloasma Uterinum.—The most important form, however, in the

symptomatic class is that due to disturbances, either functional or

organic in character, of the utero-ovarian system, known under the name

of chloasma uterinum. It appears upon the face and is usually limited

to this part, the forehead being the favorite site, although occasionally

this whole region shares in the discoloration, forming almost a “mask.”

In some instances patches appear also on the breast, abdomen, and other

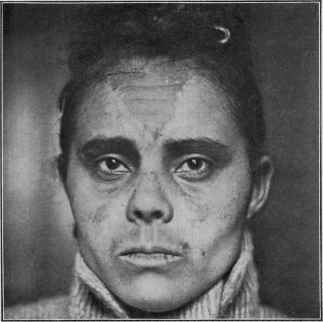

Fig. 120.—Chloasma in a light mulatto woman aged thirty, of several months'

duration; a rather sharply defined area on the central portion of the forehead, some

under the eyes, small patches on cheeks, and a long patch on upper lip. There was

utero-ovarian disturbance, with irregular menstruation.

parts. It presents sometimes as fairly well-defined patches of yellowish-

brown pigmentation, but much more commonly the plaques or areas are

ill defined, and the dividing-line between the normal and pigmented skin

is difficult of recognition. The pigmentation is more intense in bru

nettes. The skin is smooth; occasionally a mild degree of seborrhea

coexists, in which event the surface may be either oily or furfuraceously

1 Drummond, “Clinical Lecture on Some of the Symptoms of Graves’ Disease,”

Brit. Med-. Jour., 1887, i, p. 1027.

2 Hector Mackenzie, “Clinical Lecture on Graves‘s Disease,” Lancet, 1890, vol. ii,

pp. 545 and 601 (many interesting cases with pigmentation; numerous references).

3 Nicol, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1900, p. 56 (more or less general); see also Dore‘s paper,

“Cutaneous Affection Occurring in the Course of Graves’ Disease,” ibid.., p. 353.

5o8

HYPERTROPHIES

scaly, usually the former, depending, however, upon the variety of sebor-

rhea. It is seen in those between the ages of twenty-five and fifty;

rarely in those younger, and seldom after the climacteric. It is most

commonly observed during pregnancy (chloasma gravidarum), but may

also occur in connection with any functional or organic disease of the

utero-ovarian apparatus. There is during the pregnant state, as is

known, a physiologic tendency to a pronounced increase of pigmentation,

but more especially in certain situations, as along the linea alba and

about the nipples. Kaposi1 reports a curious case of a woman in whom

increased pigmentation of a large mole on her neck was the earliest sign—

in the first month—of pregnancy. In some instances this pigmentary

tendency is not only seen in the face, especially the forehead, but also

the neck, and occasionally it is extensive or almost universal, as in the

cases referred to by McLane,2 Wilson,3 Murphy,4 Crocker,5 Swayne,6

and others. It more usually appears in the early or middle period, and

may deepen in shade as pregnancy becomes advanced, disappearing,

as a rule, after confinement. In McLane‘s case it appeared during the

eighth month; in Swayne‘s, at the beginning of the last three months,

and in this instance had so occurred in three successive pregnancies. In

Crocker‘s patient the color increased with each pregnancy. As already

remarked, however, various other conditions may also occasion it, such

as ovarian irritation, dysmenorrhea, etc7

Etiology and Pathology.—The causes which have in the main

already been necessarily mentioned in speaking of the varieties are, it is

seen, numerous and of different nature. Most cases coming under ob

servation are those with patches on the face, and having some disturbance

of the utero-ovarian apparatus as the etiologic factor. In addition to

this and the other causes named may also be mentioned anemia and

chlorosis, chronic indigestion, neurasthenia, nervous shocks, and similar

agencies. Sex has a very decided influence. The malady is rare in the

male; occasionally, however, pigmentation of the face is observed, and

sometimes discoloration, more or less patchy, is seen about the crural

and perineal region. As already stated, persistent hyperemia, as in

chronic eczema of the legs, especially when associated with varicose veins,

will often leave more or less permanent pigmentation. Discoloration

is also, as known, observed as a result or part of some other maladies,

as lichen planus, pigmented sarcoma, xeroderma pigmentosum, lepra,

1 Kaposi, Trans. Berlin. Internat. Cong., 1890, vol. iv, Abth. xiii, p. 98. The

papers by Caspary, Kaposi, Ehrmann, and Jarisch on the subject, “Die Pathogenese

der Pigmentirungen und Entfärbungen der Haut,” contained therein, give a clear

presentation of the subject.

2 McLane, “Extraordinary Pigmentation of the Skin in Pregnancy,“ Amer. Jour.

Obstet., 1878, vol. xi, p. 792 (chiefly on neck, back, and thighs, patient profoundly

anemic).

3 Wilson, Lectures on Dermatology, London, 1878, p. 24 (more or less general).

4 Murphy, “Chloasma Uterinum,” Obstetrical Gazette, 1879-80, vol. ii, p. 294

(general).

5 Crocker, Diseases of the Skin (chiefly face and neck).

6 Swayne, quoted by Tilbury Fox, Diseases of the Skin, second Amer. edit., p. 402,

and also by Crocker, loc. cit. (face, arms, hand, and legs—spotty).

7 See valuable paper by Champneys, “Pigmentation of the Face and Other Parts,

Especially in Women,” St. Barth. Hosp. Rep., 1879, vol. xv, P- 233 (with review of the

subject and report of 8 cases).

CHLOASMA

509

scleroclerma, urticaria pigmentosa, etc The staining of jaundice and

the yellowish color from the ingestion of picric acid, as well as the dis

coloration produced by the external use of certain drugs, such as chrys-

arobin, need not be specially referred to, the causative factors being

usually self-evident. The chloasma following prolonged administration

of arsenic is referred to elsewhere (see Dermatitis medicamentosa).

Argyria, tattooing, and gunpowder stains are discussed later on.

The pathologic process of chloasma is, for the most part, merely an

accentuation or increase in the physiologic pigment function.1 It is

apparently under the control of the nervous system. Some observa

tions, as in Andrewes’ cases,2 suggest investigation as to the possibility

of disease of the suprarenal glands being occasionally of influence.

Gueneau de Mussy3 believed that any irritation or lesion of the nerves,

or affiliated nerves, which supplied the suprarenal capsules, from what

ever part of the abdomen, will have an influence on increase of pigmen

tation. Anatomically the sole change consists of an increased deposit

of pigment having its seat wholly or principally in the mucous layer of

the epidermis. The malady, in fact, is pathologically similar to freckles,

except in the latter there is an extremely circumscribed deposit, while

in chloasma it is patchy or diffused. In some instances pigment is also

found more deeply, as Demiéville4 and others since have observed. In

some instances, as in those following chronic diseases of the skin, the

pigmentation is due, in great part at least, to the coloring-matter of the

extravasated blood. In discolorations due to stains, as in jaundice, for

instance, the color extends deeply.

Diagnosis.—The general pigmentary cases give no difficulty,

nor does, ordinarily, chloasma utermum, the discolorations of which

are usually confined to the face. The diseases with which the latter

is most likely to be confounded are tinea versicolor, vitiligo, and chromi-

drosis. In tinea versicolor the discoloration is rarely seen on the face,

and then in connection with extensive eruption on the trunk, and, more

over, even then it only exceptionally gets higher than the lower edge of

the chin. The distribution and the extent are, therefore, usually alone

sufficient for the differentiation; but in addition to this the patches of

chloasma are smooth, the skin otherwise unchanged, whereas in tinea

versicolor there is more or less furfuraceous scaliness, and the surface

can readily be scraped off with the finger-nail, and with it the discolora

tion, as the latter is due to the causative fungus, which is rarely seated

more deeply than the superficial horny layer. The microscope could, of

1 See “pigment” of the skin and the extremely valuable contributions by Ehrmann,

“Untersuehungen über die Physiologie und Pathologie des Hautpigmentes,” Arckiv,

1885, p. 507, and 1886, p. 57 (a classic paper, with references and 11 colored histologic

cuts), and also his still more elaborate paper, “Das Melanotische Pigment,” etc,

Bibliotheca Medica, Abth. D. ii, H. vi, 1896, with 12 colored plates containing many

cuts (Fisher and Co., Cassel); also “Das Pigment der Haut,” by Unna, Monatshefte,

1889, vol. viii, p. 366 (with review and references); also Piersol‘s paper, “Develop

ment of Pigment within the Epidermis,” University Magazine, 1890, p. 571 (with cuts

and references).

2 Andrewes, loc. cit.

3 Gueneau de Mussy, Revue, Méd., Feb., 1879, quoted by Murphy, loc. cit.

4 Demiéville, “Ueber Pigmentflecke der Haut,” Virchow's Archiv, .1880, vol. lxxxi,

P- 333 (based chiefly upon a study of lentigo, with 3 histologic cuts and references).

5io

HYPERTROPHIES

course, be resorted to if necessary, but such a contingency could rarely

happen. Vitiligo, as is known, consists of depigmented or whitened

spots or patches with surrounding increased pigmentation, totally dif

ferent from chloasma, and this can readily be recognized unless hastily

and carelessly examined; but the possibility of mistake is in the fact

that the white areas may be considered the normal color, in which event

the surrounding pigmentation would be misinterpreted. The patch

of chloasma always has, however, somewhat rounded, convex borders,

whereas in the pigmentation of vitiligo inclosing a more or less rounded

area of white skin the border, of one side at least, would be just reversed

—concave.

In chromidrosis (q. v.) the discoloration is in the exuded secretion,

and it can be washed or rubbed off, although sometimes with considerable

difficulty, but usually readily with ether or chloroform; this moist or oily

condition of the surface, moreover, is unusual in chloasma, and when

rubbed, the exudation taken up by the rubbing finger shows the dis

coloration also. In view of the observations of De Amicis, Majocchi, and

Dubreuilh, indicating that exceptionally pigmentation results from the

presence of a profusion of the parasite, demodex folliculorum (q. v.),

this factor should not be lost sight of, especially in those instances

seemingly obscure etiologically. Nor is the possibility in obscure cases

of the discoloration being due to some drug or other stain medicinally

or intentionally employed to be forgotten, which, if such suspicion is

aroused, can, as a rule, readily be determined. It is to be remembered,

also, that the continued administration of arsenic sometimes produces

a more or less general pigmentation.

Prognosis.—Chloasma uterinum is usually persistent and rebel

lious, generally disappearing as the cause—pregnancy or other dis

turbance of the generative organs—subsides. In persistent cases, in

which no evident factor seems present, ovarian irritation or some disease

of the uterus is to be suspected, and such possibility substantiated or

disproved by gynecologic examination. Cases depending upon anemia,

chlorosis, and similar removable agencies are usually of favorable out

come. It is true, without disappearance of the underlying cause, the

discoloration can generally be removed by local applications, but the

effect is, as a rule, only temporary. The remediability of the more or

less generalized pigmentation of tuberculosis, cancer, etc., is dependent

upon the prognosis of the disease in question. The pigmentation conse

quent upon irritation and inflammatory diseases usually subsides sooner

or later after discontinuance of the cause, but in some cases some months

or a year or more may elapse before it has entirely disappeared; that from

chronic eczema of the leg, if in people of advanced years, is usually per

manent, though it becomes somewhat less marked. That following

syphilitic eruptions is rarely persistent.

Treatment.—Chloasma requires for its removal a careful study

of the exciting and predisposing causes. The digestion, the tone of the

general health, and the utero-ovarian organs should receive attention

as possible factors. If anemia or chlorosis is present, the proper measures

should be accordingly instituted. In fact, the constitutional treatment

CHLOASMA

511

is to be prescribed upon general principles, as there are no specific reme

dies. As in some instances it is difficult or impossible to discover any

faulty condition of the general system, in such reliance must be placed

upon local treatment; and, in fact, this latter is to be employed in all cases,

although, unless a removal of the exciting or predisposing cause is pos

sible or has ceased to persist, the relief furnished is commonly but tempo

rary.

The cases applying for treatment are usually those in which the

face is the site of the blemish,—other cases being relatively rare,—and

for the most part these are examples of chloasma uterinum. The external

treatment has in view a twofold action—a removal of the epidermic

corneous layer and upper rete cells, and with these the pigmentation

contained therein, and a stimulation of the absorbents. Occasionally

the action must also take in the lower rete cells. The external treatment

is, in fact, similar to that employed in the removal of freckles, to which

the reader is referred for the method of application of the remedies—

corrosive sublimate, lactic acid, hydrogen peroxid, the ointment of

bismuth subnitrate and white precipitate, and the peeling pastes. As

a rule, however, in chloasma the stronger applications are necessary,

and sometimes actual blistering is required. It should be noted, more

over, that certain remedies which produce active exfoliation or blistering,

instead of removing the pigment, may tend to increase it, such as, for

instance, mustard and cantharides, and these are to be avoided. The

application selected should be employed in the weaker strength at first,

in order to test the sensitiveness of the skin; it is to be made several

times daily when possible, and as soon as branny exfoliation begins to

show itself or active irritation supervenes, it should be discontinued

until such symptoms have subsided. When the temporary disfigure

ment is not objected to, treatment can be more energetic, pushing it to

the point of more decided exfoliation, after which a mild soothing salve,

such as cold cream, can be applied for a day or two until the surface is

smooth again, and then, if pigment still remains, as it commonly does,

although usually less marked, active treatment is resumed, and so on

until it is entirely removed; or if the selected remedy is unsuccessful,

then changing to another. Hydrogen peroxid acts more through

its bleaching property, and occasionally satisfactorily without push

ing it in greater strength to the point of producing a mild exfoliative

dermatitis.

My own experience would indicate that the most valuable applica

tions are, in the order named, corrosive sublimate solution, lactic acid,

salicylic acid, the peeling pastes, and hydrogen peroxid.

Argyria is the term applied to the discoloration which follows the

prolonged administration of silver nitrate, a rare occurrence at the

present day, but not infrequent at the period when this drug was the

chief remedy in the treatment of epilepsy. It has also been stated to

follow the repeated applications to the throat, and Crocker (loc. cit.)

“met with a case in which the blueness did not develop for many years

after the topical application had ceased to be made.” In an instance

512

HYPERTROPHIES

observed by Neumann1 in the case of a physician, who for gastric ulcer

was in the habit of injecting into his stomach daily, through an esopha-

geal tube, two or three syringefuls of a solution containing 24 grains (1.5)

of silver nitrate to 3 ounces (96.) of water, and in whom, after the twelfth

injection, according to the patient's statement, the discoloration began

to appear. In the instance reported by Riemer,2 the first sign appeared

after about 280 grains had been taken. Koelsch3 has observed two cases

of generalized argyria in women handling silver leaf. According to

Branson, confirmed by Pepper,4 the earliest indication of the development

of the discoloration is the occurrence of a dark-blue line on the edges of the

gums, very similar to that produced by lead, but somewhat darker. The

color of the skin resulting, as well known, is of a bluish-gray or slate color,

and when once established, is permanent. It is general over the surface

and also on the adjoining mucous membranes, but is most pronounced

on those parts exposed to the light, as the face and hands. The hair

and nails also share in the discoloration, the hair having a faint reddish

tinge. According to the investigations of Riemer and Neumann,5 the

pigment is found in the form of reduced silver, and in all parts of the

skin except the rete cells and the glandular epithelium, and also in the

subcutaneous connective tissue. The greatest deposition is just below

the rete, in the uppermost papillary layers of the corium, where it ap

pears as a sharply defined blackish border, and it is also abundant in

the membranæ propriæ of the sweat-glands. A deposit is likewise

found in the internal organs, with the exception (quoting Lesser)6 of

the central nervous system.

When the discoloration is once established, it is permanent, although

Neumann7 records an instance in which there occurred some lessening

of the intensity in the course of several years; and Yandell8 reported 2

such patients (epileptics) who contracted syphilis, for which the adminis

tration of potassium iodid was conjoined with mercurial vapor-baths,

and during which treatment there was gradual disappearance of the

discoloration—in one completely, in the other practically so. Others,

however, who have since tried this plan have not been so fortunate.

Tattoo-marks.—Tattooing, or the mechanical introduction of pig

ments into the skin, is a well-known process. The coloring-matter used

consists of carbon, cinnabar, carmin, and indigo, and when once thor

oughly imbedded, is permanent. The chief interest dermatologically

lies in the attempts at successful removal, an end exceedingly difficult,

and without excision or destructive action almost, if not wholly, im-

1 Neumann, “Ueber Argyria,” Medicinische Jahrbücher’,1877, p. 369 (with résumé,

several histologic cuts, and references).

2 Riemer, Archiv der Heilkunde, 1875, pp. 296 and 385.

3 Koelsch, München, Med. Wochenschr., Feb 6, 1912,p. 304 (professional argyria,

etiology, and prophylaxis).

4 Branson, Pepper, cited in United States Dispensatory.

5 Neumann, Lehrbuch der Hautkrankheiten.

6 Lesser, Ziemssen's Handbook of Skin Diseases, p. 455.

7 Neumann, Medicinische Jahrbücher, 1877, p. 382, also cited by Lesser, Ziemssen's

Handbook of Skin Diseases, p. 455.

8 Yandell, Amer. Practitioner, 1872, vol. v, p. 329.

CHLOASMA

513

possible of attainment. Various methods have been extolled from time

to time, having usually as a basis the production of a reactive destructive

inflammation which results in crusting, the crust dropping off, and in

successful instances the pigment cast off with it, leaving a superficial

or pronounced scar, according to the particular plan employed. The

French methods, which seem to have the most support, excepting excision

or cauterization, are the plans advocated by Brault1 and by Variot,2

with neither of which I have had any personal experience. Brault‘s

method consists, after thorough cleansing of the surface, of tattooing in

of a solution of 30 parts of zinc chlorid in 40 parts of water; mild in

flammatory reaction ensues, but usually slight, a crust forms, and after

some days falls off, leaving a scar; a repetition is sometimes necessary.

Variot‘s plan is first to put on the mark a concentrated solution of tannin,

which is then tattooed in, making punctures close together: he then rubs

the silver nitrate stick firmly over the surface, allows it to remain for

several minutes, and then wipes it off. There is a slight inflammatory

reaction, occasionally trifling suppuration; the part blackens, a super

ficial crust or eschar forms, which in one or two weeks drops off, leaving

an insignificant scar which becomes scarcely noticeable. Dubreuilh3

has warmly extolled “shaving” off the involved skin, supplementing by

skin-grafting if necessary.

Fig. 121.—Cutaneous punch or trephine.

In recent years Ohmann-Dumesnil,4 Nelson,5 and Skillern6 have

reported success in their removal by tattooing in, after first rendering

the surface aseptic, of glycerol of papoid spread upon the surface.

Others,7 including myself, have not, however, been successful with this

method.

The methods which I have chiefly employed are those of electrolysis,

the cutaneous trephine, and excision. Electrolysis is successful only

with small spots. The needle is introduced, as a rule, from the edge,

slantingly toward the center—as if to undermine it; the whole border

is thus gone around, the punctures being about one-eighth inch apart.

The strength of current varies from 1 to 4 or 5 milliampères, and with

each introduction allowed to act from one-half to one minute or a trifle

longer. It is in reality a destructive method, reaction taking place, a

thin eschar or crust forming, and finally cast off, leaving a superficial

1 Brault. Annales, 1895, p. 33.

2Variot, Compt.-Rend. Soc. de Biol., 1888, p. 636.

8 Dubreuilh, “Détatoage par décortication,” Annales, 1907, p. 367.

4 Ohmann-Dumesnil, New York Med. Jour,, 1893, vol. lvii, p. 544, and St. Louis

Med. and Surg. Jour, (tattoo-marks and powder-stains), 1900, vol. lxxviii, p. 65.

Later, ibid., Oct., 1908, this same writer states that caroid is superior to papoid for

this purpose.

5 Nelson, New York Med. Jour., 1804, vol. lix., p. 272 (chiefly as to powder-stains).

6 Skillern, Philada. Med. Jour., 1898, vol. i, p. 1166.

7 Cantrell and Stout, Bangs and Hardaway‘s Amer. Textbook, p. 949.

33

514 HYPERTROPHIES

scar. If any remains, that part is to be gone over again. The cutaneous

trephine or punch can be used in two ways: if the spot is very small, it

can be “punched,” and the projecting disc cut off, and a slightly larger

disc of healthy skin made by a larger trephine transplanted; if the area

is greater, then a small or moderate sized punch can be used on several

parts of its surface, the discs cut off, and the denuded places dressed with

an antiseptic powder, such as I part of acetanilid and 7 parts of boric

acid. After these have healed, new places can be treated in the same

manner until it is entirely removed. With care and trouble transplanta

tion could also be practised in such larger areas. When the mark is on

soft yielding parts, excision is a good plan, the skin at the edges being

dissected under and drawn together. At my service at the Jefferson

Medical College Hospital we have recently tried applications of carbon-

dioxid snow, with moderate success, when the pigment is not too deeply

imbedded.

Powder-stains are practically similar to tattoo-marks. If the case

comes under observation shortly after the accident, many of the marks

can be picked out. Later this same plan may prove of service, but much

better is the method of removal by a cutaneous trephine of extremely

small caliber, as originally suggested by Watson1 and subsequently

brought into more general use through the paper by Keyes.2 The punch

is placed over the powder speck and given a slight rotary motion, pressing

firmly, but not going down to unnecessary depth; the little disc of skin

tends to jut ou.t, can be snipped off, and the minute cavity filled with

powdered subsulphate of iron or with a paste of tincture of benzoin

and boric acid, or with the compound powder of boric acid and acetanilid

mentioned under tattoo-marks. With care and skill, not cutting too

deeply, the little scars left become practically unnoticeable. More

recently the application of hydrogen dioxid has received favorable com

ment, Crile,3 Rhoads,4 and Clark5 reporting satisfactory and rapid

results. It is applied in full strength, freely and often, and if not irri

tating, it can be kept constantly applied on lint, wetting this from time

to time. Crile used a “concentrated solution,” which was applied until

a white zone had appeared around and under the grains, and until bub

bling, which was also produced, had fully ceased, after which they may be

readily removed with a pointed instrument. Clark used a solution of

1 part glycerin and 3 parts hydrogen dioxid, and applied freely, on

lint, if not irritating, and the stains disappeared. In addition to these

several methods the tattooing in of the glycerol of papoid or caroid

has also been commended, employed as in tattoo-marks.

Blue stains,6 or pigmentation, are not infrequently seen at and about

1 Watson, “Discotome,” Med. Record., 1878, vol. xiv, p. 78; and “Gunpowder

Disfigurements,” St. Louis Med. and Surg. Jour., 1876, vol. xxxv, p. 145.

2 Keyes, “The Cutaneous Punch,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1887, p. 99; Busch, Berlin,

klin. Wochenschr., 1884, vol. xxi, p. 306, originally suggested a similar, but larger,

trephine for the removal of small growths.

3 Crile, Cleveland Med. Gazette, 1896-97, vol. xii, p. 183.

4 J. N. Rhoads, “Powder-Stains,” American Medicine, 1901, vol. i, p. 16.

5 Clark, ibid., June 1, 1901, p. 384.

6 Gottheil, “Blue Atrophy of the Skin from Cocain Injection,” Jour. Cutan. Dis.,

1912, p. 1, with résumé of other cases (Thibiérge, Horand, Gaillard) with references.

NÆVUS PIGMENTOSUS

515

the sites of hypodermic injections, and exceptionally the pigmentation

may be associated with slight atrophic changes; the stains are thought to

be due partly, directly or indirectly, to the needles and possibly also to

adulteration of the injected material.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |