| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

VARIOLA

(W. M. Welch)

Synonyms.—Smallpox; Fr., Petite-vérole; Ger., Blättern or Pocken; Ital., Vajuolo.

Definition.—Smallpox is an acute infectious disease character

ized by an initial fever of about three days’ duration, succeeded by an

eruption passing through the stages of papule, vesicle, and pustule,

ending in incrustation, and leaving pits or scars; the fever either inter

mitting or remitting in the papular, and increasing in the pustular,

stage.

Symptoms.—The period of incubation of smallpox is seldom less

than eight days or more than fourteen, commonly from ten to twelve

days. The symptoms constituting the initial stage, or stage of invasion,

are usually ushered in suddenly and often with considerable violence.

Among the earlier symptoms is a distinct chill, which may be mild or

severe, and which is immediately followed by rise of temperature. The

thermometer often registers 1030 or 1040 F. on the first day, and may

be a little higher on the succeeding days. The pulse and respirations

keep apace with the febrile movement. Prostration is often extreme.

Vertigo on assuming the erect position is a frequent symptom. At this

time vomiting and epigastric tenderness are commonly observed. Head

ache usually begins at the onset of the disease, and continues until the

appearance of the eruption. It may be excruciating, and, when the fever

is high, accompanied by delirium. Convulsions are very common in

children, and at times there may be coma. Pain in the lumbar and

sacral regions comes on early, and, like the headache, subsides at the

beginning of the eruptive stage. This symptom is not invariably present,

although it occurs in over one-half of the patients. In hemorrhagic cases

the backache is often violent. A peculiar prodromal rash, varying in

frequency in different epidemics, often makes its appearance on the

second day, and disappears within forty-eight ‘hours. It is stated by

some authors to be scarlatiniform in character, but in my experience it

has more often resembled measles, and has been designated “roseola

variolosa.” I have observed this rash more frequently in varioloid

than in severe cases of variola.

The eruption usually appears upon the third day of illness, mani

festing itself first upon the face, particularly about the forehead, temple,

and mouth, and then rapidly appearing upon the scalp, neck, ears,

forearms, and hands. In the course of twenty-four hours the body and

VARIOLA

48l

lower extremities become involved. The eruption continues to increase

for two or three days before its definite limit is reached. The lesions

consist at first of minute red points, which in the course of twenty-four

hours develop into elevated papules with characteristic shot-like indura

tion. On the third day of the eruption many of the lesions will be found

to contain a little clear serum, and by the fourth or the fifth day all the

papules will have been converted into vesicles with cloudy or milky

contents. These continue to enlarge, attaining their maximum size

about the seventh or the eighth day. Many of the vesicles will be seen

to have the central depression or umbilication, which is a feature of

diagnostic value.

Fig. 118.—Well-marked discrete smallpox on ninth day, showing lesions in the stage

of beginning crust-formation (courtesy of Dr. J. F. Schamberg).

The stage of suppuration usually commences about the sixth day,

when the contents of the vesicles are yellowish and decidedly puriform.

In the process of development the pustules lose their umbilication and

become large and globular. The reddish areola, which at first surrounded

the lesions, acquires greater breadth and a more intense hue. Where

the pustules are thickly set, as upon the face, great swelling and intumes

cence take place, so distorting the patient‘s features as to render him

completely unrecognizable. The eyelids are frequently so edematous

as to preclude the possibility of their being opened. The lips, nose, and

ears are greatly tumefied, and the scalp is swollen and painful. The

mucous membranes are also attacked, the lesions manifesting themselves

upon the lips, buccal and nasal mucous membrane, tongue, pharynx,

and at times the larynx.

31

482

INFLAMMATIONS

• Upon the appearance of the eruption, or, more commonly, on the

second or the third day thereafter, the temperature falls, the head

ache, backache, vertigo, vomiting, etc., cease, and the patient believes

himself on the road to convalescence. The subsidence of these symptoms,

however, except in mild cases, is only temporary, for upon the commence

ment of the stage of suppuration the temperature again begins to rise

and continues high until the decline of the suppurative fever. The

height of the fever is proportionate to the extent of the eruption, the

temperature varying from 1020 F. in mild cases to 1040 or 1050 F. in

confluent smallpox. Headache, restlessness, and delirium are common

during this stage, the patient at times sinking into the typhoid state.

During the stage of desiccation, which begins about the eleventh

or twelfth day, the tumefaction subsides, and the normal contour of

the features is gradually restored. The contents of the pustules dry

into crusts, which process is often accompanied by intense itching.

The crust-formation begins in the center of the pustules, leading to a

secondary umbilication. In regular cases of variola vera the shedding

of the scabs requires a period of three to four weeks, making the entire

duration of the disease about five or six weeks. After the scabs have

fallen the skin presents a red, spotted appearance, and is disfigured by

scars or pits. These are deepest on the face, particularly about the end

and alæ of the nose. The hair is often lost, but thorough restoration

usually follows.

The clinical history of smallpox is not complete without reference

to other forms and varieties of the disease. The above description

; relates more particularly to cases in which the eruption is either dis

crete or semiconfluent. The grades of smallpox cover a wide field of

variation, from an eruption consisting of but a few small pustules,

scarcely sufficient to identify the disease, to an eruption completely

covering the entire cutaneous surface. During the past few years there

has appeared in this country an epidemic of smallpox so unprecedentedly

and uniformly mild as to constitute an unwritten chapter in the history

of the disease. Its benignancy can be best estimated when it is stated

that the mortality-rate among many thousand vaccinated and unvac-

cinated cases throughout the United States during the first three months

of 1901 was not much over 1 per cent. The clinical picture is that of

mild varioloid, despite the absence of any such modifying influence as

commonly exists in this form of the disease. Therefore a brief descrip

tion of varioloid will suffice to portray also this unusually mild form of

smallpox.

The prodromal symptoms of varioloid may be severe or mild; in

the latter case it being possible to prophesy a sparse eruption. The

duration of the initial stage is more variable than in variola vera, varying

from twenty-four hours to five days. The eruption of varioloid differs

from that of variola only in that it is milder in its course and shorter in

duration. The lesions may be limited to a very few on the face, or they

may be semiconfluent. In the milder forms the lesions may become

abortive at an early period; in the severe forms the evolution of the lesions

may not differ from unmodified smallpox. The cutaneous involvement

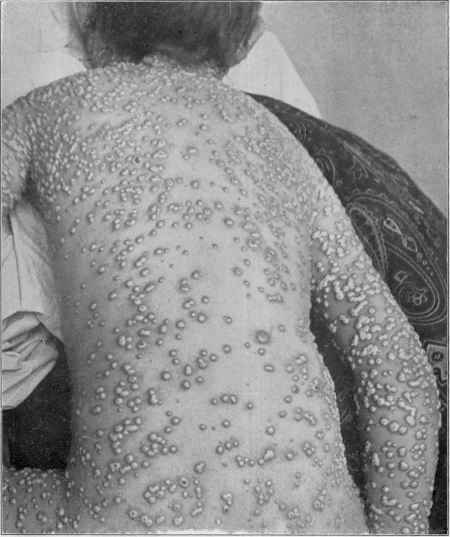

Plate XVI.

Variola—an extensive case showing numerous lesions on trunk as well as face and

extremities (courtesy of Dr. G. W. Wende).

VARIOLA 483

is often superficial, being limited to the upper layers of the skin. As

a result, we have a shorter eruptive course, earlier desiccation, more

rapid shedding of the scabs, and fewer and less disfiguring scars. Occa

sionally the lesions develop into large, solid papules, conic in form, with

vesicular summits. On shedding of the crusts, instead of pits, tuber-

culated or warty-looking excrescences are left. These, however, flatten

down and disappear in the course of time. Secondary fever is either

absent or trivial in character.

The eruption of confluent variola is usually preceded by severe

prodromes, such as high fever, intense headache and backache, vomit

ing, etc. The temperature does not descend as low on the appearance

of the eruption as in milder cases, nor does the remission continue so

long. On account of the extensive involvement of the skin, redness and

swelling begin early, the former as early as the second day. Many of

Fig. 119.—Variola—moderate case (courtesy of Dr. G. W. Wende).

the thickly set papules coalesce, and in the formation of vesicles the

confluence is so great as often to cover almost the whole cutaneous sur

face. The confluent pustules are usually flat, and sometimes present a

milky or pasty appearance. At the height of the eruption the patient

is unrecognizably disfigured. The mucous membranes of the nose,

mouth, pharynx, and larynx are often intensely involved. The soft

palate, tonsils, and tongue may become greatly swollen, and edema of

the glottis may lead to a fatal termination. Upon rupture of the pustules

and decomposition of the contents the stench often becomes unbearable.

Secondary fever is usually very high, and death frequently occurs at this

period from septicemia and exhaustion. When recovery takes place,

convalescence is long and tedious, and apt to be interrupted by the occur

rence of boils and abscesses.

The names petechial, purpuric, and hemorrhagic variola are applied

to the different phases presented by malignant smallpox. A pete-

484

INFLAMMATIONS

chial rash is sometimes seen at the close of the initial stage, about the

time the true eruption appears or should appear. This is quickly

followed by the purpuric or hemorrhagic lesions, which lead rapidly

to a fatal termination. At other times petechiæ and ecchymoses appear

between the papules or vesicles, the latter often filling up with a san-

guinopurulent fluid. Variola purpurica is the most malignant form of

the hemorrhagic type. At the end of the initial stage, which is par

ticularly characterized by intense backache and excessive prostration,

a diffuse scarlatinoid efflorescence appears on various parts of the trunk

and extremities. This gradually assumes a dark-red or purplish colora

tion, which does not disappear on pressure. In addition, petechiæ,

vibices, and ecchymoses occur. The face soon becomes involved,

presenting a swollen and puffy appearance. Indistinct sanguinolent.

vesicles, blackish or leaden-gray in color, may be seen in various localities.

As the disease progresses, the skin becomes almost black or a deep indigo

color. Hemorrhages occur from the various mucous membranes.

Death is the almost inevitable termination. In the form designated

variola hæmorrhagica pustulosa the vesicles, instead of filling with

purulent material, contain a bloody fluid. This condition of the vesicles

may be limited to certain localities or may be generalized, with petechiæ

and ecchymoses interspersed. Hemorrhages occur from the nose,

mouth, and intestinal and urinary tracts. This form runs a somewhat

longer course than purpura variolosa, but is almost as certain to end

fatally.

Among the common complications and sequelæ of smallpox may

be mentioned erysipelas, boils, abscesses, and disease of the eyeball,

middle ear, respiratory tract, and joints. Erysipelas occasionally

comes on during desiccation, and is apt particularly to involve the face.

Pneumonia sometimes occurs. Furuncles and abscesses are extremely

common. But few patients pass through a well-marked attack of small

pox without suffering from boils during the later stage of the disease.

Gangrene of the skin, especially of the scrotum, is a complication which

usually leads to a fatal termination.

Diagnosis.—In the initial period of the disease great assistance

may be gained by determining the presence or absence of vaccine marks

and their number and character. Furthermore, by ascertaining whether

or not smallpox is prevalent, and whether the patient has been exposed

to the disease. During the eruptive stage variola may be confounded

with varicella, pustular syphiloderm, impetigo contagiosa, drug-rashes,

etc.

The onset of varicella is very different from that of variola. There

is usually no distinct febrile stage preceding the eruption. It is true

that in many cases of extremely modified smallpox no reliable history

of an initial stage can be obtained, so that in such cases the diagnosis

must be made from the appearance and behavior of the exanthem alone.

It is important to bear in mind the following facts: that the lesions of

varicella make their appearance as distinct vesicles containing perfectly

clear serum; that they are usually seen first on parts of the body covered

with clothing, and especially on the back, where they are apt to be most

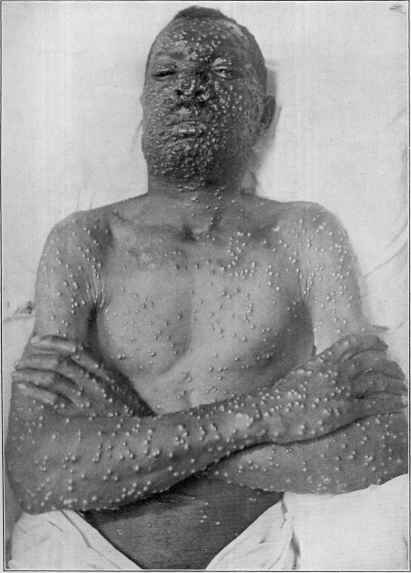

Plate XVII.

Variola on the seventh day, showing the usual preponderance of lesions on the face,

hands, and wrists (courtesy of Dr. J. F. Schamberg).

VARIOLA

485

abundant; that they make their appearance in successive crops, and

may be seen in every stage of development; that they vary very greatly

in size; that they are unilocular and have an epidermal covering so deli

cate as to be readily broken by the finger-nail; that they are rather soft

and velvety to the touch; that many of them enlarge to a considerable

circumference by peripheral expansion, while others are as small as millet

seeds; that they are not umbilicated except by desiccation beginning

in their centers; that they run their course to the formation of crusts

in two to four days; that the crusts are thin, brown, and friable, and

when they have fallen off, red instead of pigmented spots remain; and

that but few of the lesoins are followed by permanent scars. The exan-

them of smallpox, on the other hand begins in the form of papules which

are firm and dense to the touch, feeling somewhat like grains of sand

buried in the skin; that they usually appear first on the face and then

on other parts of the body; that the papules slowly develop into vesicles

with milky or turbid contents; that the vesicles in well-marked cases

are umbilicated; that they are multilocular and have an epidermal cov

ering so dense as not to be easily broken by the finger-nail; that the

eruption prefers the exposed parts of the body, such as the face, hands,

and arms, being often only sparsely seen on the trunk; that the vesicles

are usually quite uniform in size; that they change into pustules; that

the eruption requires in severe cases twelve or more days to pass through

its various stages, while in extremely mild cases not more than five or

six days are required; that the crusts which form are thick and very

dark, and when they have fallen off, there remain pigmented spots and

more or less pitting.

Despite the above differentiation, it must be admitted that small

pox may occur in a form so atypical as to make the differential diag

nosis a matter of great difficulty. In such cases the patient should be

isolated and carefully watched for a few days, when the nature of the

disease will, as a rule, be easily determined.

The lesions of the pustular syphiloderm frequently resemble very

closely those of smallpox. The difficulty of diagnosis is often increased

from the fact that the eruption in syphilis is not infrequently preceded

by fever and various aches and pains, and that the lesions begin as

papules and end in pustules. Instead of appearing all at once, the

eruption of syphilis usually comes out in successive crops. Pustular

syphiloderm, however, may be distinguished by the milder constitu

tional symptoms during the initial stage; by appearance of the lesions

in successive crops; by the formation, at the summits of the papules,

of small vesicles which later become pustular; by the large indurated

base of each vesicle; by the absence of typical umbilication; by the

tendency to ulceration of some of the lesions; by the slower course of the

eruption, and by concomitant symptoms of syphilis and a history of

infection. In doubtful cases a few days’ observation of the patient will

usually suffice to determine the question; and the examination for

the spirochæta pallida and the Wassermann test can now also be

resorted to.

Impetigo contagiosa has been confounded at times with the mild

486 INFLAMMATIONS

variola of recent years. It may be easily differentiated by the absence

of fever, by the usual limitation of the lesions to the face and hands,

by the fact that they are primarily vesicular or bullous, rapidly becoming

pustular and drying into flat, ocher-colored crusts, and by the extreme

superficiality of the process.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |