| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

VACCINAL ERUPTIONS

Synonym.—Vaccination rashes.

It is beyond the scope of this volume to go into the method and

details of vaccination more than briefly, and chiefly as to the cutaneous

aspect of the resulting lesions, and the sometimes engendered or pro

voked more or less generalized eruptions. Vaccinia, or cow-pox, is a

well-known affection among certain animals, but more especially the

cow, and while never occurring spontaneously in the human subject,

its artificial production in the latter by inoculation, as strenuously pointed

out by Jenner, affords a protection against variola.

The operation of vaccination is sufficiently well known to need no

comment.1 For the first few days nothing special is observed: possibly

a little congestion or irritation from the procedure. After the lapse of

forty-eight hours or thereabouts a minute papule is noticed at the point

or points of inoculation, which in the course of two or three days more

has developed into a vesicle. Where several or more have simultaneously

arisen at contiguous points of the inoculation spot these usually merge,

and the subsequent course is, as a rule, the same as when there is but

one inoculation point, although in some instances the resulting larger

vesicle shows its compound nature. When several inoculation points

are, as the result of intention or accident, at some distance apart, each

develops and usually goes through the regulation course, although some

times one undergoes full development and the others partial. The vesicle

enlarges peripherally, and in from five to seven days after the operation

is a somewhat distended, well-formed pea- to finger-nail-sized, translu

cent vesicle, frequently with a perceptible or well-marked tendency to

central depression or umbilication. At this stage, in successful, and

usually especially pronounced in instances of first vaccination, there is

a well-defined wide encircling red or pinkish-red areola, with some

inflammatory infiltration or hardness. At this time—in the sixth to the

eighth day—constitutional symptoms of variable degree present: slight

temperature elevation, accelerated pulse, general malaise, often some

gastrointestinal uneasiness, and the axillary or neighboring lymphatic

glands are somewhat enlarged and tender. The lesion is usually ex

quisitely sensitive, and slight or intense itchiness may, at this time, be

1 Hutchins, Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, April 23, 1898, advises a simple, ingenious,

painless method, especially valuable in children, in whom even the suggestion of a

trifling scarification often meets with opposition. The part to be vaccinated is first

cleansed, and a small piece of cotton is wet with liquor potassæ and laid on the spot for

two or three minutes; it is then removed, and the soapy mixture thus formed, with the

epidermis and skin secretion, wiped off, and the place gently rubbed with a piece of

damp cotton; the epidermis, softened by the liquor potassæ, comes readily away, and an

excellent bloodless absorbent spot is thus made, on which the vaccine is placed and let

dry on in the usual way.

VACCINAL ERUPTIONS

487

complained of. The vesicular contents now become cloudy, and by

the ninth or tenth day desiccation gradually sets in, the inflammatory

areola begins to fade, and the general symptoms subside, the lesion then

finally, by the thirteenth to the fifteenth day, presenting as a dime- to

silver-quarter-sized yellowish or reddish-brown crust, with an encircling

narrow line of redness, which latter slowly disappears; and usually in

a little less than three weeks from the date of vaccination the crust has

fallen off, disclosing a pinkish or reddish scar which slowly becomes

whitish and shows minute pits or depressions—the sites of the primary

points of inoculation. Exceptionally, generally in those cases in which

healing has been accidentally delayed, a keloidal tendency has been

noted, but usually of slight development.

All cases are not regular in their development and course: in some

the vesicle develops early, in others it is retarded. Cases vary con

siderably in intensity, in some, probably from accidental complication

or inoculation or individual peculiarity of the tissues, the zone of red

ness presents a decidedly erysipelatous aspect, and may involve a greater

part of or the entire region. In fact, so severe may this erysipelatous-

looking inflammation be that it may assume a phlegmonous character

and some sloughing of the vaccinated spot occur, with associated lym

phangitis and marked swelling of the neighboring glands. The con

stitutional symptoms may also be correspondingly severe. In other

instances new vaccinal lesions develop in the neighborhood of the vac

cinated spot, and even to some extent beyond, and while these may be

simply a part of the disease vaccinia, it is much more probable that they

are the result of accidental inoculation in consequence of carrying the

virus from the vaccine lesion by means of the nails or fingers. General

vaccinia has, however, it is stated, been observed, although the possi

bility of a coincident impetigo contagiosa might afford an explanation

of many such instances. In some cases of vaccination, usually unsuc

cessful, after a partial formation of the vaccine vesicle, it is ruptured,

and granulation tissue of a raspberry- or strawberry-like character de

velops, and sometimes, if untreated, will persist for weeks without show

ing the slightest tendency to spontaneous disappearance; in some of its

aspects presenting a resemblance to granuloma pyogenicum. In some

such instances there has apparently been aft accidental, but usually harm

less, inoculation of an adventitious organism or material, and which prob

ably has taken place subsequently to the vaccine inoculation. It may

be that in some of these cases the tubercle bacillus is implanted upon

an unfavorable soil and fails to gain proper nutritional support, and dis

appears on the institution of almost any astringent or antiseptic applica

tion.

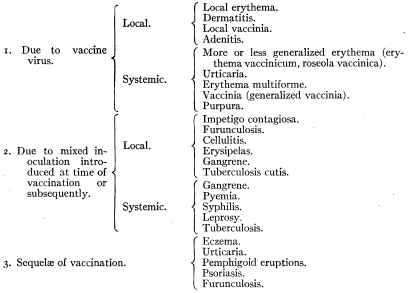

Malcolm Morris, in his excellent presentation of the subject, has

divided the vaccinal rashes1 into two classes: (1) Eruptions due to pure

1 The reader desirous of pursuing the subject is referred to Behrend‘s paper (read

before Dermatologic Section of International Medical Congress, London, Aug., 1881),

Arch. Derm., 1881, p. 383 (translated by Alexander); Morrow, Jour. Cutan. Dis.,

1883, p. 166, with references; Malcolm Morris’ paper, with discussion (read before

Dermatologic Section, British Medical Association, Birmingham, Eng., July, 1890),

Brit. Med. Jour., Nov. 29, 1890—abstract of paper in Brit. Jour. Derm., 1891, p. 26;

488 INFLAMMATIONS

vaccine inoculation, and (2) eruptions due to mixed inoculation, which

Frank has slightly enlarged and modified, and which, with few immaterial

changes, embody my own views and present clearly the eruptive com

plications: some not uncommon, others extremely rare, and some ques

tionable. It is true that to some extent these divisions are more or less

arbitrary, and there is difficulty in placing some affections as respects

the exact etiologic local or general relationship, and hard-and-fast lines

cannot always be drawn; but the scheme is about as satisfactory as can

be made under present conditions, and gives a faily clear presentation of

the subject.

The most frequent and usually evanescent and harmless of these

are the localized or general erythema, urticaria, erythema multiforme, a

regional, vaccinia-like eruption (often probably impetigo contagiosa),

impetigo contagiosa, and a pseudo-erysipelatous or erysipelatous in

flammation, or other accidental dermatitis. A neighboring adenitis,

as already referred to, is usual to a moderate degree, but sometimes is

extremely developed. Local or generalized erythema, erythema multi-

forme, and urticaria may present at any time between the date of vac

cination and the crusting period; erythema multiforme and urticaria,

especially the latter, even to a later period. Behrend called attention

to the fact that there seem to be two periods for the occurrence of vac-

cinal eruptions—in the first three days, or not until the eighth or ninth.

While true in the main, there are many exceptions. They present no

also Frank‘s paper, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1895, p. 142; and Dyer‘s, New Orleans Med.

and Surg. Jour., Feb., 1896; Colcott Fox, Brit. Med. Jour., July 5, 1902; Towle, Boston

Med. and Surg. Jour., Sept. 4, 1902; Stelwagon, Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc., Nov. 22,

1902; Pernet, Lancet, Jan. 10, 1903; Corlett, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1904, p. 495 (with

illustrations and references to recent papers). See also under Pemphigus and Derma

titis herpetiformis.

VACCINAL ERUPTIONS

489

special peculiarities from the ordinary types of these maladies, but are

usually of shorter duration. In erythema multiforme the erythematous

and erythematopapular manifestations are most common, but the vesic

ular and bullous lesions may also occur. The various other cutaneous

complications are rare. Eczema developing from the inoculation site

or elsewhere occasionally follows, but probably only in those with a clear

eczematous tendency; and exceptionally the disappearance of an existing

chronic eczema is promoted by the vaccinal operation (see Eczema).1

Psoriasis has in rare instances taken its start at the point of inoculation,

or has made its first appearance closely following this procedure, as

already referred to under that disease; in all probability vaccination

has no etiologic relationship except as possibly its action as a local or

general excitant or its disturbing influence upon the nervous system.

Indeed, in this as in many other instances of eruption occurring during

or immediately subsequent to vaccination it is more than probable that

they are purely coincidental and in no way connected with or due to

this operation. The layman and, flagrantly, the antivaccinationist,

and sometimes, too, the physician, are too prone to consider all such

eruptions as effects; in short, it should be clearly understood that cuta

neous outbreaks occurring at such time are not necessarily vaccinal,

although it is true many of them are.

Most of the pemphigoid eruptions encountered, usually following

one to several weeks after the operation, have doubtless been examples

of bullous impetigo contagiosa. Exceptionally, however, pemphigus

or pemphigoid lesions have been observed.2 A few instances of seeming

relationship have come to my notice, and of serious character; bovine

virus was used. In this connection the observations and study of the

etiology of acute pemphigus by Pernet and Bulloch3 are of great interest

(see Pemphigus). In their report and analysis of cases, in a number the

subjects were found to be butchers, and the disease to have originated

from a small wound resulting from their occupation; further, in one case

a pemphigoid eruption seemingly followed inoculation from a similar

eruption on the teats of a cow. Others are also mentioned where the

disease occurred in those having to do with animals or animal products,

and instances of the existence of pemphigoid eruptions in animals are

referred to. These facts have suggested the possibility that the rare

cases of pemphigus, usually of grave character, exceptionally observed

developing after vaccination, may thus be explained.

Irrespective of the usual transitory rashes, it has been believed,

1 Great care should be exercised, however, as to vaccination in moist, raw, oozing

cases of eczema; as in a few instances, in young children, more or less general inocu

lation of such surfaces has followed. One such case was shown at the Internat. Derm.

Congress in Berlin, Sept., 1904.

2 See a recent interesting paper by Bowen, “Six Cases of Bullous Dermatitis Follow

ing Vaccination, and Resembling Dermatitis Herpetiformis,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1901,

p. 401; and Howe, “Cases of Bullous Dermatitis Following Vaccination,” ibid., 1903,

p. 254. Other references will be found under Dermatitis herpetiformis.

3 Pernet and Bulloch. Brit. Jour. Derm., 1896, pp. 157 and 205. See also Bowen's

suggestive paper, “Acute Infectious Pemphigus in a Butcher, during an Epizoötic of

Foot and Mouth Disease, with a Consideration of the Possible Relationship of the

Two Affections,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1904, p. 253; also “Report of Bureau of Animal In

dustry,” abstract, Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, 1909, vol. lii, p. 1679.

490

INFLAMMATIONS

ever since the operation of vaccination has been advocated, that the

process is not without danger as to the inoculation of other more serious

diseases. There can be no question that pure virus of bovine origin

should be employed, and that with this, as with any operative procedure,

care, caution, and cleanliness are essential prerequisites to safety, and

with proper observance of which the operation is an absolutely harmless

and safe one. With careless operators impure virus, and more especially

uncleanly patients, the accidental inoculation of tuberculosis, leprosy,

syphilis, and other affections becomes a possibility. It is doubtless true

that in most of the serious sequences of vaccination that neither the

operator nor virus is at fault, but that the damaging infection takes

place later as a result of carelessness, negligence, or uncleanliness on the

part of those vaccinated. The possibility of inoculation of tuberculosis

has been questioned, but suggestive cases are on record where localized

tuberculosis cutis (q. v.) has developed at the point of vaccination, and

that much being admitted, general infection might likewise be produced.1

As to the accidental inoculation of leprosy, there has long been a belief

that such has often occurred (Beaven Rake), but authentic examples

are rare. Daubler's2 2 cases seem to show this possibility, and doubtless

other instances might be found upon investigation. Added to this is

the fact that bacilli lepræ have been found in the vaccine lymph taken

from a leper (Arning).3 Examples of syphilis inoculation through vac

cination are rarely observed at the present day, and then only

through gross carelessness or through pure accident unconnected with

the procedure itself; but that it was, while not frequent, occasionally

observed formerly is attested by the observations of Hutchinson, Four-

nier, R. W. Taylor, and others.

Vaccinal eruptions cannot always be prevented, referring especially

to those that arise through the vaccine virus itself, but such are prac

tically harmless and short-lived, and rarely give rise to trouble. Even

taking into consideration the occasional accidental mixed infections,

which also with rare exceptions are not of serious import, such cases

weigh as nothing compared to the benefit bestowed upon mankind by

the operation. With proper care, however, on the part of the caretakers

of the cattle from which the virus is derived, rigorous inspection of the

animals, and extreme precaution in the collection and preservation of

the vaccine, added to caution and cleanliness on the part of physician

1A case under my own observation, of development of lupus at the site of vaccina

tion, and immediately following the same, and which is referred to in discussing that

disease, is one in point. This patient and two others were vaccinated from the same

crust; the reactionary symptoms in all were severe, in two quickly followed by mixed

general symptoms of what seemed, as described to me, of mixed septicemic and tuber

culous character, followed by death; and in my patient, at that time a robust young

female child, followed by the development of lupus, which had persisted and extended

when I saw her ten or twelve years later. The history of the cases was given me by a

physician, the brother of my patient, but owing to the years which had elapsed and the

nature of the accident, further details could not be obtained, and there naturally

remains an element of doubt about the true character of the condition which carried

off the other patients.

2 Daubler, “Ueber Lepra und deren Kontagiosität,” Monatshefte, Feb. 1, 1889,

p. 123.

3 Arning, Jour. Lepr. Inves. Com., No. 2, Feb., 1891, p. 131, quoted by Dyer

(loc. cit.).

VACCINAL ERUPTIONS 491

and patient, before, at the time, and subsequently to the operation until

complete healing has taken place, the occurrence of serious accidents

would practically be placed beyond the bounds of possibility. Human

virus should, of course, never be employed. Morris, among other rec

ommendations for the prevention of vaccinal eruptions and accidents,

urges that strict antiseptic and protective treatment should be carried

out immediately after the vesicles have developed, and, further, that

the cases should be seen by the vaccinator until the wounds have healed.

But little need be said about the treatment of the various erythem-

atous, urticarial, and other ordinary rashes occasionally observed, as

it is in these the same as in these eruptions occurring independently

of the operation. The rare serious cases, too, are likewise managed on

the same principles laid down elsewhere for the particular eruption

presenting.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |