| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

URTICARIA

Synonyms.—Hives; Nettlerash; Fr., Urticaire; Ger., Nesselsucht; Nesselaus-

schlag.

Definition.—Urticaria is an inflammatory affection characterized

by evanescent whitish, pinkish, or reddish elevations or wheals, some

what variable as to size and shape, and attended by itching, stinging,

and pricking sensations.

Symptoms.—The eruption in urticaria usually comes out sud

denly, occasionally being preceded by burning or itching of variable

intensity. It is erythematous in character and consists of scanty or

profuse pea- to bean-sized elevations, linear streaks, or small or large

irregular patches, or an admixture of these forms. It may be limited

in extent and distribution, or more or less general and abundant. While

no part of the body is exempt from possible manifestations, covered

parts, especially the lower trunk, buttocks, and upper outer chest, around

about the axillary regions, are favorite localities. The outbreak may

be preceded and accompanied by symptoms of gastric derangement, and

exceptionally and in extensive and markedly acute cases by some febrile

action. In many cases, however, the cutaneous eruption is unaccom

panied by any other recognizable symptoms. The lesions are fugacious

in character, disappearing and reappearing in the most capricious manner.

They are somewhat firm, with an average size in the typical wheal of a

flattened large pea. They may vary in tint in different cases, and in

different lesions in the same case. They are pinkish or reddish, with

usually a whitish central portion. At times they are almost entirely

whitish, with a narrow, pinkish areola. The subjective symptoms are,

as a rule, quite marked, consisting of stinging, intense burning or itching,

or a combination of these symptoms. Rubbing or scratching the parts

to obtain relief will ordinarily provoke a new outcropping in such regions.

The lesions are distinctly evanescent, lasting from several minutes to a

fractional part of a day, the average being about an hour or two. The

intervening skin is perfectly normal in appearance, new lesions present

ing rapidly from time to time. In exceptional cases the individual

lesions may persist for several days or a week or longer—urticaria per-

stans. In some instances, with or without a few or more wheals on other

parts, the disease presents itself as an ill-defined pufrmess of the hands

1 Marquez, Gaz. hebdom., 1889, p. 91.

180

INFLAMMATIONS

and fingers and feet, accompanied with intense subjective symptoms of

burning and itching.

During an outbreak of urticaria, and in exceptional instances with

out actual outbreak, and even in the interim of attacks, it is possible in

some persons to bring out linear wheals by simply rubbing the finger or

drawing a lead-pencil somewhat firmly over the surface. In this manner

letters, symbols, and words may be produced at will and last for minutes

or hours. This, or a phase of it, constitutes the so-called urticaria

factitia, dermatographism, autographism.

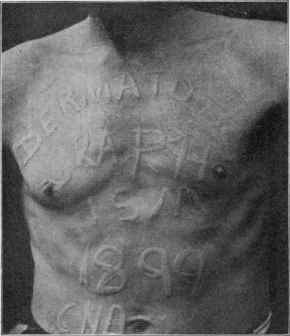

Fig. 34.—Dermatographism. Tracing done with the blunt end of a lead pencil,

making slight pressure, the “welts” reaching full and prominent development in

several minutes (courtesy of Dr. C. N. Davis).

Barthélemy1 has thoroughly studied this peculiar condition, and

finds that while it is commonly associated with urticarial attacks at

short or long intervals, it not infrequently may exist independently, and

the subject learn of its existence only accidentally. One such instance

as the last named has come under my notice. The lines or figures

brought out at will in these cases last a variable time—from twenty or

thirty minutes up to twenty-four hours. The tendency in some in

stances, according to Barthélemy, occasionally disappears temporarily.

The eruption in urticaria is not always confined to the external

surface. The mucous membranes of the mouth, throat, larynx, and

1 Barthélemy, Etude sur le Dermographisme ou Dermoneurose Toxivasomotrice,

Paris, 1893 (an admirable and complete monograph with a review bibliography of the

literature and notes of many cases and 17 illustrations).

URTICARIA 18l

possibly the intestinal mucous surfaces, may exceptionally be the seat

of wheals and edematous swellings, a number of instances of which have

been recorded, more especially in recent years (Delbrel, Madison Taylor,

Hinsdale, Merx, and others).1 Occurring about the throat and larynx,

the symptoms are sometimes alarming.

Urticaria may be acute or chronic; in most instances the former,

the outbreak coming on rapidly, with slight variations as to the intensity

of the attack. The lesions may continue to appear and disappear in the

most capricious manner, for several hours to two or three days, and then

disappear entirely; or there may be one more or less extensive outcropping

of wheals, reaching its acme in an hour or so, and then gradually fading

away. The duration of an acute attack is from several hours to several

days, the average being twenty-four to forty-eight hours. It may

recur in some instances from time to time at intervals of weeks or months

upon exposure to the necessary etiologic factor or factors. In exceptional

cases of urticaria, but more particularly in the hemorrhagic form, pig

mentation results which may last for some months or longer.

Chronic urticaria, fortunately, is not very common. In these cases

the lesions are usually evanescent, as in the acute type, and very often

somewhat scanty, but fresh efflorescences continue to appear from day to

day and from week to week almost indefinitely, the patient‘s general

health often suffering from the constant worry and discomfort produced

by the itching and burning.2 Very exceptionally the lesions, or some of

them, instead of being evanescent, are somewhat persistent, lasting days

or weeks—urticaria perstans (Pick); some cases of which are doubtless

examples of prurigo nodularis. Other instances of persistence of the

lesions, some assuming annular and gyrate forms, have been described

as urticaria perstans annulata et gyrata, but these cases seem to belong

more properly to erythema multiforme (q. v.).

Instead of the characteristic lesions of the disease, the eruption

may be atypical, thus arising the types known as giant urticaria, papular

urticaria (urticaria papulosa), hemorrhagic urticaria (urticaria hæmor-

rhagica, purpura urticans) bullous urticaria (urticaria bullosa).

The conditions variously described as giant urticaria, urticaria

tuberosa, urticaria œdematosa, and acute circumscribed edema are

closely allied or identical, varying usually as to degree, and presenting the

cutaneous symptoms of tumor-like swellings of evanescent character.

1 Delbrel, “Contribution a l‘etude de l‘urticaire des voies respiratoires,” These de

Bordeaux, 1896 (reviews 25 cases from literature and adds 2 of his own); Madison Tay

lor (larynx and skin), Philadelphia Med. Jour., April 2, 1898; Hinsdale, Philadelphia

Polyclinic, July 30, 1898; Freudenthal (recurrent and chronic of larynx and skin), New

York Med. Jour., Dec 31, 1898; Chittenden (buccal, pharyngeal, and nasal mucous

membrane and skin, chronic in character, with recurrent hematemesis), Brit. Jour.

Derm., 1898, p. 158; Goodale and Hughes (chronic and of tongue only, controlled by

salol), Amer. Jour. Med. Sci., April, 1899; Merx (recurrent, tongue, throat, and skin;

with bibliography), Munch, med. Wochenschr., 1899, p. 1174; F. A. Packard, Soc‘y

Trans., Philadelphia Med. Jour., July 22, 1899, and Archives of Pediatrics, 1899, P-

729 (showing apparent connection between respiratory disturbances and urticarial

eruptions).

2 Under the name “urtica solitaria” Vörner (Dermatolog. Zeitschr., Jan., 1913, p. 1)

records several (4) cases where general recurrent urticarial attacks finally gave place

to an occasional appearance of a single lesion, and usually when recurring this lesion

always appeared in the same place.

182

INFLAMMATIONS

They are frequently a part of a more or less general urticaria in which

most of the symptoms are of the ordinary wheal type, presenting the

edematous swellings here and there, more especially about the eye

lids, mouth, and ears. Occasionally, however, acute circumscribed

edema seems to be entirely or sufficiently independent of urticarial

manifestations, and free from subjective symptoms, to be entitled to

separate description (q. v.).

Urticaria papulosa, also known as lichen urticatus, consists essen

tially of an urticaria in which the lesions are discrete and scattered

and usually upon the limbs. They may appear as small, more or less

typical wheals, which disappear, leaving behind persistent eczema-like

papules, though somewhat larger than the papules in the latter disease.

Or the lesions may, for the most part, appear as papules from the start,

with here and there a scattered typical wheal. In addition to the serous

exudation of the ordinary wheal, there seems to be in this type a mark

edly inflammatory element. These papules usually itch intensely, and

as a result the summits of many of them are scratched and covered with

minute blood-crusts. They disappear but slowly, new papules coming

out from time to time. This type may last from one to several months

or longer, and tends to recur. It is almost entirely confined to young

children and to those in a depraved state of health. It is rather rare in

this country. 1 It is possible that this form, instead of being a true urti

caria, may be an example of mild prurigo, a disease which is not uncom

mon in Austria and other European countries.

Urticaria hæmorrhagica seu purpura urticans is characterized by

efflorescences similar in size and shape to those of ordinary urticaria

except that there is a variable amount of hemorrhage into the wheals.

It is probable that in the majority of these cases the purpuric condition

is the primary one, and the wheal formation secondary; in fact, in some

cases the purpuric element may be of a somewhat grave character, with

hemorrhages from the mucous membranes.

Urticaria bullosa, or bullous urticaria, is that form of urticaria in

which the lesions become capped with a vesicle or bleb or in which

the wheals are rapidly displaced by blebs. This anomaly is seen most

frequently upon the extremities, although this lesion may in excep

tional instances constitute the larger part of the eruption—so much

so as to suggest pemphigus, dermatitis herpetiformis, or bullous ery

thema multiforme. Apparently the inflammatory action has been

sufficiently great to give rise to considerable fluid effusion, in this manner

the wheals resulting in the formation of bullæ.

Etiology.—Urticaria may occur at all ages and in both sexes,

and in all countries. It is much more frequent, however, between

the ages of early childhood and middle adult age, and is possibly some

what more common in the female sex. The papular type is more fre

quent in England2 than elsewhere, and is almost exclusively seen in

1 Chipman, California State Jour, of Med., June, 1910, states that it is not uncom

mon in San Francisco, and thinks the flea is frequently a factor there in its pro

duction.

2 Colcott Fox, “On Urticaria in Infancy and Childhood,'’ Brit. Jour. Derm., 1890,

pp. 133 and 176.

URTICARIA

183

children. There are many causes, but there is some peculiar individual

predisposition necessary, inasmuch as the same cause may not produce

the eruption in different subjects. In some instances a hereditary in

fluence or predisposition is observed, especially in the cases associated with

giant lesions and edematous swellings. The etiologic factors may be

considered under the heads of external and internal causes, or direct and

indirect.

As exemplifying the external causes may be mentioned the bites

or irritation produced by jelly-fish, mosquitos, fleas, stinging nettle,

certain kinds of caterpillars, bedbugs, etc. Constant scratching or any

persistent skin irritation, as in scabies and pediculosis, will at times

also be provocative. While, as a rule, in urticaria produced by this class

of etiologic factors the urticarial lesions appear only at the points or im

mediate neighborhood of the irritation, yet this is not always the case, as

in particularly susceptible individuals a general outbreak may result.

The internal or indirect causes are numerous, here again the indi

vidual peculiarity having a potent contributory influence. Most of this

class act through the stomach and intestinal tract. Among the more

common factors in this class may be mentioned oysters, clams, crabs,

lobsters, shrimps, mussels, fish, pork, more especially sausages and

scrapple, veal, nuts, mushrooms, strawberries, and cucumbers. In

addition to the articles of food named, others may be causative in special

instances, owing to some striking idiosyncrasy, such, for instance, as

oatmeal and butter. The irritation from intestinal worms may also be

the cause in the urticarias of children. The malady is not infrequent in

immigrants during their first several months’ stay in our country, doubt

less due to the complete change of diet and mode of living. An attack

may also result from the ingestion of certain medicinal substances, more

especially copaiba, cubebs, chloral, turpentine, quinin, opium, the

iodids, and many of the coal-tar products. The use of antitoxins has

added another cause occasionally provocative.

Emotional or psychic causes, such as anger, fright, or sudden grief,

will sometimes excite an outbreak, more especially if occurring during

or directly after a meal, the process of digestion being apparently inter

fered with, possibly permitting the development of toxins. Urticaria

is at times observed in association with malaria, jaundice, albuminuria,

and diabetes mellitus. The not infrequent occurrence of the disease in

rheumatic and gouty individuals would point to these constitutional con

ditions as likewise predisposing. Functional and organic diseases of the

uterus may also be found to be the important underlying etiologic factors,

especially in the recurrent and chronic cases. Surgical operations, more

particularly upon the abdominal cavity, exceptionally appear to be of

causative influence. In fact, whatever gives rise to profound nervous

disturbance must be looked upon as of some import. My own impres

sion has been that these various factors act principally by the disturbing

influence they may have upon the act of digestion. Beyond question,

toxins from without or within—autointoxication—must in this, as in some

other diseases of the skin, especially erythema multiforme, be considered

as the most common cause of the outbreak. The action of nervous

184 INFLAMMATIONS

influence, direct or indirect, is shown by a case reported by Oliver,1

where the eruption was due to eye-strain, persisting or recurring when

a change in lenses was necessary. Ravitch2 believes disturbances of the

thyroid to be a factor of importance in chronic urticaria.

In the past several years biologic investigations have been thought

to point out as probably first indicated by Wolff-Eisner that urticaria

(and other toxic dermatoses) may be due to a hypersensitiveness to a

foreign albuminoid substance—the albumin not being sufficiently split

up by the intestinal juices, such products being absorbed into the cir

culation, and provoking an outbreak. A hypersensitive or anaphylactic

condition may be thus brought about which makes the individual acutely

responsive to even the smallest quantity of such toxic substances. The

faulty or imperfect preparation of this protein for safe absorption might

be directly or indirectly due to any of the various etiologic factors named.

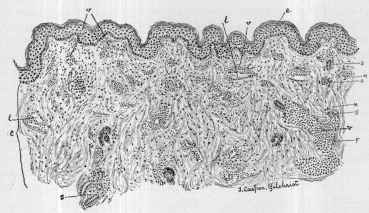

Fig 35-—Urticaria—section of a wheal: e, Epidermis, practically no alteration; c,

corium, showing acute inflammatory changes, swollen and infiltrated with serous exuda

tion, with the blood-vessels (v, v, v), especially those accompanying the sweat-ducts

(s, s, s, s) dilated and surrounded by and containing numerous polynuclear leukocytes;

lymphatic vessels (l, l) and spaces also enlarged, containing granular matter; numerous

mast-cells (m, m) scattered through the corium (courtesy of Dr. T. C. Gilchrist).

Pathology.—The pathology of urticaria is closely similar to that

of erythema multiforme. The disease is an angioneurosis, the lesions

being, primarily at least, due to vasomotor disturbance, which may be

of diverse origin, but doubtless most commonly toxinic; the angioneurotic

view has, however, some distinguished opponents. Barthélemy believes

dermatographism to be due to a toxic vasomotor dermatoneurosis.

In urticarial lesions dilatation following spasm of the vessels results in

effusion, and in consequence the overfilled vessels of the central por

tion are emptied by pressure of the exudation, and the pink or reddish

color gives place to central paleness, while the pressed back blood ac-

1 Oliver, Philadelphia Med. Jour., January 14, 1899.

2 Ravitch, “The Thyroid as a Factor in Urticaria Chronica,” Jour. Cutan. Dis.,

1907, p. 512; also Leopold-Levi and de Rothschild, Compt. rend. Soc. de Biol., Nov.,

1906.

URTICARIA

185

centuates the bright red tint of the periphery. Philippson,1 from animal

experiments, believes, with Heidenhain, that the secretion of lymph is

not a passive process due to intravascular pressure, as contended by

most dermatologists, but that a secretory action of the vascular endo-

thelium is involved; and that the edema of urticaria is similarly pro

duced by direct action of poisonous substances upon the vessels in the

neighborhood. Török and Hari's2 experimental studies are also in

accord with this view. Gilchrist's3 experimental observations led him

to a somewhat similar conclusion: that a true wheal is an acute, inflam

matory edematous swelling, due either to local inoculation of irritating

substances, as insect bites, etc, or to drugs or to some toxin probably

originating in the alimentary canal, the irritating agent producing death

of cells, which is followed by acute inflammatory changes. Wright and

Paramore4 believe that an attack of urticaria may be directly due to a

diminution of the lime salts in the blood, with consequent associated de

fective blood coagulability—is of the nature of a serous hemorrhage.

The pathologic anatomy of a wheal, studied by various observers

(Vidal, Unna, Gilchrist, and others), shows it to be a more or less firm

elevation of a circumscribed or somewhat diffused collection of semi-

fluid material, more especially in the upper layers of the skin. While it

has its usual seat in the derma proper, in intense cases the subcutaneous

tissue may also be involved in the process. Gilchrist found the epi

dermis unaltered, but the whole corium the seat of acute inflammatory

changes; the blood-vessels, especially those accompanying the sweat-

ducts, enlarged, containing and surrounded by a large number of poly-

nuclear leukocytes; the lymphatic vessels and the juice-spaces were

also much enlarged, containing only granular material; large numbers

of polynuclear cells were found to pervade the whole region, even into

the papillæ, but only a few had found their way into the epidermis.

There were numerous mast-cells throughout the corium, and the latter

was much swollen and infiltrated with serous exudation.

Diagnosis.—This rarely gives any difficulty. In fact, the disease

is so common and well known that the diagnosis is usually made by the

patient. The character of the lesions, their evanescent nature, the

irregular and general distribution, usually abundant upon covered parts,

and the accompanying intense itching, will afford sufficient basis for its

recognition. These points will serve to differentiate it from erythema

multiforme, to which it bears some resemblance. Urticaria bullosa

might, upon first and careless inspection, lead to a confusion with pem

phigus or dermatitis herpetiformis, but the usually preceding wheal

upon which the bleb arises, and the presence here and there of the ordi

nary type of the eruption, together with the history and course, will

prevent error.

1 Philippson, Giorn. ital., 1899, Fasc. vi, p. 675, abstract in Brit. Jour. Derm., 1900,

p. 217.

2 Török and Hari, “Experimentelle Untersuchungen über die Pathogenese der Urti

caria,” Archiv., 1903, vol. lxv, p. 21.

3 Gilchrist, “Some Experimental Observations on the Histopathology of Urticaria

Factitia,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1908, p. 122.

4Paramore (experimental study), Brit. Jour. Derm., 1906, pp. 239 and 248.

186

INFLAMMATIONS

Chronic urticaria has essentially the same features as the acute

disease, except the eruption is usually less abundant. It is not to be

forgotten that both pediculosis and scabies, as well as the irritation of

other animal parasites, may occasionally be responsible for scattered

wheals, but the other eruptive features of such maladies (q. v.) are usu

ally sufficiently distinctive to prevent confusion.

Prognosis.—The acute disease is of short duration, disappearing

spontaneously or as the result of treatment in several hours or a few

days; it may recur upon exposure to the exciting cause. Patients

with urticarial tendency should give special attention to the dietary,

and avoid those articles which may cause indigestion or which expe

rience has taught them may, owing to some idiosyncrasy, provoke

the disease. The prognosis of chronic urticaria is to be guarded, and

will depend upon the ability to discover and remove or modify the

etiologic factor. Recurrences are not uncommon.

Treatment.—Acute urticaria, the most common expression of

the disease, is usually due to stomach or digestive disturbance of acute

character. If the case is urgent and seen early, an emetic, to rid the

stomach quickly of the offending material, may be given; this is, however,

rarely required. The usual plan is to give a purge. For this purpose

there is nothing better than the antacid magnesia, although any of the

various salines will usually act satisfactorily. In addition to the purga

tive, an antacid should be administered at several hours’ interval, such

as sodium salicylate or sodium bicarbonate or benzoate; of the salicylate,

5 to io grains (0.35-0.65) three or four times daily, and of the others,

10 to 20 grains (0.65-1.35) at a dose; in children the doses should be

smaller. The diet for the time should be plain. In the vast majority

of the acute cases this simple plan of treatment will prove sufficient

to end the attack. If the attack should be somewhat persistent, the

alkali should be continued, and, in addition, small doses of salol and a

few grains of charcoal added to each dose. The calcined magnesia, too,

should be administered about every other night until the disease has

yielded.

It is, however, the chronic cases of urticaria which often tax our

therapeutic resources. Such cases require the most rigorous and care

ful examination, in order to discover, if possible, the underlying etiologic

factor or factors. The possibility of diabetes, albuminuria, disease of

the liver, and utero-ovarian disease being the influential cause should be

eliminated. The urine should be carefully and repeatedly examined,

for this sometimes gives the clue to the acting factor. Particular atten

tion should be given to the digestive apparatus, for probably this, as in

the acute cases, is the most common source of the disease. The patient‘s

habits as regards the use of alcohol and the use of drugs should also be

inquired into, as having a possible bearing.

There are many cases, it is true, of chronic urticaria in which the

etiology remains obscure, even after the most careful investigation,

and such cases must be treated empirically. Experience has taught

that the remedies most frequently successfully used in such cases are

quinin, sodium salicylate, atropin (Schwimmer and many others),

URTICARIA

187

pilocarpin (Pick), ergot, potassium bromid, salol, strophanthus (Riffat),

ichthyol, strychnin, calcium chlorid (Wright), along with saline laxa

tives. Arsenic may also be tried in resistant cases, although, except

indirectly, in small doses as a tonic, it is usually disappointing. The

most efficient of these in a given number of cases are atropin and sodium

salicylate.

Frequent and repeated doses of saline laxatives sometimes cure

when all the ordinary remedies have failed to make a permanent im

pression. For this purpose calcined magnesia, taken every second or

third night, or Carlsbad salts, magnesium sulphate, sodium sulphate,

Hunyadi Janos water, or Friedrichshall water, taken every morning

or every second morning, can be prescribed. The dose should be suffi

cient to produce free and prompt action, but not sufficiently large to bring

about a condition of diarrhea. The following also has given me satis

faction:

R. Sodii sulphat. granulat., 3ij (64.);

Sodii chlorid,, 3iiss (10.);

Sodii bicarbonat., 3vss (22.).

This should be kept in a closely stoppered, wide-mouthed bottle,

and one to two teaspoonfuls taken dissolved in a half to a tumblerful

of hot water twenty or thirty minutes before breakfast; or in some

cases it seems to act better when taken in smaller doses—a half to one

teaspoonful—before each meal. In obstinate cases spinal galvaniza

tion, static insulation, and the static current with the roller electrode

applied along the spine should be tried. Ravitch, in the belief that the

thyroid gland is a factor, has prescribed in atrophy and functional inac

tivity desiccated thyroid gland in chronic cases with alleged favorable

results; while in enlarged glands and hypersecretion such remedies as

thyroidectin, strophanthus, bromids, atropin, and x-ray.

It is understood that in all these cases the diet is to be carefully regu

lated, and all indigestible foods interdicted, and especially those articles

which experience has taught are not infrequently causative factors.

Coffee and tea in excess should also be avoided; in fact, these drinks

should be, in rebellious cases, forbidden absolutely. Resorting for a

time to an exclusively milk diet will sometimes prove curative, or at

least remove the disease for a time. In persistent cases of the disease

which have proved rebellious to all plans, especially those dependent

upon neurasthenic conditions, change of scene and climate will some

times give temporary, and not infrequently permanent, freedom.

If the eruption is extensive the itching is likely to be so trouble

some a feature that the patient loses much sleep, and in such instances,

occasionally, recourse must be had to potassium bromid, chloral, sul-

phonal, acetanilid, phenacetin, and the like. In a few instances two or

three daily doses of acetanilid or phenacetin in moderate quantity have,

as already intimated, afforded more or less permanent relief. Opiates

are usually to be avoided, inasmuch as they often increase the subjective

symptoms.

In most cases of urticaria it is found necessary to resort to local

applications to give some relief to the intense itching and burning which

188

INFLAMMATIONS

usually characterize the malady. The most efficient are those remedies

which are known to have an antipruritic action. Carbolic acid in

lotion form is one of the most valuable antipruritics in our possession.

It may be prescribed as in the following:

R. Acid, carbolici, 3ss-3j (2.-4.);

Glycerini, 3ss (2.);

Alcoholis, 3j (32.);

Aquæ, q. s. ad 3viij (256.).

Liquor carbonis detergens is another valuable preparation, and

may be used in the strength of 1 to 2 or 3 ounces (32. to 96.) to the

pint (500.) of water. A lotion of thymol, such as the following, will like

wise be found of value:

R. Thymolis, gr. viiss-xv (0.5-1.);

Glycerini, 3ij (8.);

Alcoholis, 3ij (64.);

Liquor potassæ, 3j (4.);

Aquæ, q. s. ad 3viij (256.).

Alkaline baths are also of great benefit in some cases. These may

be made with borax, sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, 1 to 4

ounces (32. to 128.) to the bath of about 30 gallons; ammonium muriate,

1 to 2 ounces (32. to 64.) to the bath, is also useful. The patient should

remain in the bath from several minutes to ten or fifteen minutes, and

the temperature should be sufficiently warm that chilliness does not occur.

In mild cases, and even in some of the more severe cases, the use of a

dusting-powder on the affected surfaces will be sufficiently soothing, and

has the advantage of cleanliness and ease of application. For this pur

pose any of the ordinary dusting-powders, such as zinc oxid, rice flour,

talc, and boric acid, can be used.

Ointments are rarely of service in the ordinary type of this disease,

but in the types described as the vesicular and bullous varieties they

may be demanded for their soothing and protective influence. For

this purpose the plain zinc oxid ointment, with 5 or 10 grains (0.35 or

0.65) of resorcin or carbolic acid to the ounce (32.), will prove satis

factory. A boric acid ointment—1 dram (4.) of boric acid to the ounce

(32.) of cold cream—may also be of use. If there is a good deal of

irritation, the calamin-zinc-oxid lotion may likewise be employed in

these cases.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |