| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

PEMPHIGUS

Synonyms.—Fr., Pemphigus; Ger., Pemphigus; Blasenausschlag.

Definition.—Pemphigus is an acute or chronic bullous disease,

characterized by the formation of scanty or numerous irregularly

scattered, variously sized, rounded or oval blebs, arising from appar

ently normal or moderately reddened skin, and which may or may

not be accompanied by mild or severe constitutional disturbance.

Numerous so-called varieties of this rare and as yet obscure disease

have been described, based chiefly upon the duration, age of the patient,

and the clinical characters and behavior of the eruption. The division

is in many respects purely arbitrary. The whole subject of pemphigus

is, in fact, at present chaotic, and it is a matter of difficulty even to the

trained dermatologist to know what to include and what not to include

under this head. Many of the cases formerly considered in this class,

372

INFLAMMATIONS

and still so considered by some German writers, have been gathered

together to form the group constituting the dermatitis herpetiformis of

Duhring.1

The presence of a bleb or blebs does not, however, as often con

sidered by many physicians, constitute pemphigus, as such lesions are

often seen as an accidental or unusual manifestation in other diseases,

such, for example, in urticaria (urticaria bullosa), erythema multiforme

(erythema bullosum), dermatitis herpetiformis, just referred to, pom-

pholyx, dermatitis venenata, leprosy, and some others. On the con

trary, pemphigus is a malady in which the lesions consist, primarily at

least, of distinct watery rounded blebs, of more or less general distribu

tion, without ring or other peculiar formation or special tendency to

group, and appearing irregularly or in successive crops, and, as a rule,

running a chronic course, with exacerbations. The subjective symptoms

usually consist of tenderness, soreness, and burning, and less frequently

itching.

The varieties of pemphigus can be described under the heads of pem

phigus acutus, pemphigus chronicus, pemphigus foliaceus, and pemphigus

vegetans. The terms “benignus,” “malignus,” “gangrænosus,” “hæmor-

rhagicus,” etc, sometimes added to pemphigus, are self-explanatory.

The cases described under the headings “Pemphigus Contagiosus”

Pemphigus Neonatorum, Pemphigus Epidemicus, etc, while included,

really represent, I believe, extensive and grave types of impetigo con-

tagiosa.

Symptoms.—Pemphigus Acutus.2—Acute pemphigus includes all

1 Recent papers on the classification of bullous diseases by Bowen and by Bronson,

with discussion, are to be found in the Trans. Amer. Derm. Assoc. for 1905, and Jour.

Cutan. Dis., 1906, pp. 110-217, and by Corlett, ibid., 1906, p. 464 (an analysis of 65

bullous cases); Zeisler, “Pemphigus,” Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, 1907, vol. xlix, p. 270

(with report of cases). Winfield, “Pemphigus and Bullous Dermatoses,” Jour. Cutan.

Dis., 1908, p. 566 (with bibliography); Macleod, ‘‘The Present State of Our Knowledge

of Pemphigus,” Practitioner, 1909, No. 82, p. 371; Pernet, “Pemphigus and Dermatitis

Herpetiformis,” Brit. Jour. Derm., Jan., 1910, reports a case of acute septic pem

phigus in a woman, followed after convalescence and recovery by an eruption of the

type of dermatitis herpetiformis; Hartzell, “Toxic Dermatoses; Dermatitis Herpeti-

formis, Pemphigus, and Some Other Bullous Affections of Uncertain Place,” Jour.

Cutan. Dis., 1912, p. 119; Brocq, Annales, Jan., 1912, p. 1, endeavors to simplify and

clarify the complicated subject of the classification of the bullous diseases.

2 Some literature on acute pemphigus: Pernet and Bulloch, “Acute Pemphigus: A

Contribution to the Etiology of the Bullous Eruptions,” Brit. Jour. Derm., 1896, pp.

157 and 205. This admirable paper refers to the various acute types, especially to that

in adults due to infection from animals or their products. The subject is presented in

its clinical, etiologic, bacteriologic, and histopathologic aspects—with numerous litera

ture references. The reader is referred to this paper for many references made in my

own text, especially as to bacteriologic findings. Hadley and Bulloch, Lancet, May 6,

1899 (fatal case in butcher, starting in finger injury); Ravogli, Cincinnati Lancet-

Clinic, April 27, 1889, p. 481; Schamberg, Annals of Gynecology and Pediatry, Feb.,

1901, p. 321 (fatal case, apparently due to vaccination); Whipham, Lancet, 1896, i, p.

1219 (2 cases; arsenic treatment, 1 death, 1 recovery; with some bacteriologic experi

ments by S. R. Wells); Robinson, Manual of Dermatology, p. 234; Rose, Montreal Med.

Jour., Jan., 1899, p. 50 (in the course of a fatal case of alcoholic delirium); Caie, Brit. Med.

Jour., 1903, vol. i, p. 308, a case of acute malignant pemphigus, ending fatally in twelve

days; the patient, a male adult, worked among cattle, and shortly before the erup

tion had pricked his hand while washing sheep; Howe, “Cases of Bullous Dermatitis

Following Vaccination,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1903, p. 254 (with several case illustrations;

a series of 10 cases, all, except 1, occurring in those recently vaccinated; 6 of these cases

died); Bowen, “Acute Infectious Pemphigus in a Butcher, During an Epizootic of

PEMPHIGUS 373

those cases in which the course is more or less limited, and the termi

nation, within several weeks or a few months, in recovery or death.

Its occurrence has been denied, but occasional observations, now con

siderable in number (Damon, Rayer, Cazenave, Neumann, Allen,

Payne, Behrend, Shillitoe, Roach, Van Harlingen, and others), leave

no doubt as to its existence. It is, however, rare, and seen for the most

part in children of early age, although it is also exceptionally seen in

the adult. It is occasionally observed (Hardy) in young girls between

the period of puberty and full sexual maturity with menstrual difficulties

(so-called pemphigus virginum, pemphigus hystericus). In its clear

type (blister fever, febris bullosa, pemphigus febrilis) the eruption

usually comes out suddenly, with premonitory symptoms of malaise,

slight or severe febrile action, chilliness or rigors, and other evidence of

Fig. 89.—Pemphigus in a negress aged thirty-one, of two months’ duration, showing

the fresh, tense, and older flaccid blebs on upper arm; eruption general. Irregular

febrile disturbance, but otherwise patient‘s health seemed good.

mild or grave systemic disturbance. The lesions are variously sized

from that of a pea to that of a pigeon's egg or larger, are generally quite

abundant, and irregularly distributed over the surface; they are dis-

Foot and Mouth Disease, with a Consideration of the Possible Relationship of the Two

Affections,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1904, p. 253 (reviews the subject of acute pemphigus,

especially as to its possible origin from animal sources, and gives a résumé of reported

cases with references); Saundby, Lancet, Oct. 1, 1904, reports a case of acute pem

phigus in a butcher‘s apprentice; Corlett‘s case, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1908, p. 7, with

circinate and hemorrhagic bullous lesions, apparently due to streptococcic infection

and ending fatally, seems to me to belong here rather than in the group erythema mul-

tiforme as reported; Grindon, “Acute Septic Pemphigus,” ibid., 1900, p. 439 (death;

case illustration; patient had to do with cattle and other animals); Pollitzer, “A Fatal

Case of Bullous Dermatitis,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1911, p. 209— a male, aged fifty-six,

beginning as an intensely itchy erythrodermia, and later developing pemphigoid lesions,

and, soon after, profound toxemia; had been in good health except for a chronic diffuse

nephritis which had apparently given no trouble; death within six weeks; postmortem

and bacteriologic findings and experimental inoculations negative.

374 INFLAMMATIONS

tended or somewhat flattened, come out at one time or in rapid succession

or in distinct crops, and, as a rule, arise from skin showing no preliminary

change; sometimes, however, from a slightly hyperemic surface. Some

are usually surrounded by a narrow red halo. Generally clear at first,

they often become milky and opaque, sometimes hemorrhagic, and

exceptionally gangrenous. In other instances the eruption is unaccom

panied by pronounced constitutional involvement, and in others the

febrile action and other systemic symptoms of varied nature continue

for the first week or two, until subsidence of the cutaneous phenomena

sets in; in such instances complete recovery usually takes place in several

weeks to one or two months.

In some of the febrile cases grave symptoms present or continue

to increase in severity, the throat and mouth show serious involvement,

the blebs become flaccid and puriform, and exceptionally the under

lying surface, gangrenous (Lenhartz), and death follows in one to

several weeks. In some instances the disease, after the more acute

outbreaks have subsided, gradually becomes less active, the lesions

are less numerous, and it goes into the chronic form.

The blebs disappear, sometimes partly by absorption, with desic

cation and crusting, or sometimes purely by desiccation and crusting,

with or without previous accidental or spontaneous rupture; when

the crust falls off, slight temporary redness or staining is noted, but

there is no permanent trace left.

The acute type is usually observed as isolated cases, but it has, or

a disease simulating it, been observed (Colrat, Köhler, Bernstein, and

others) to occur in epidemic form (pemphigus epidemicus, pemphigus

contagiosus); in some instances with but slight constitutional symp

toms or entirely free from such, and in others moderately active and oc

casionally severe. These doubtless are similar to the contagious or

infectious cases observed in the newborn—pemphigus neonatorum

—to be referred to. It is highly probable that many of the reported

epidemic and contagious cases are examples of impetigo contagiosa

and bullous varicella. The benign pemphigus contagiosus described

by Manson as quite common in the tropics is probably a variety of

impetigo contagiosa; it is usually diffused in children, but in adults

chiefly about the axillary and genito-crural regions, and in the latter

sometimes representing doubtless “dhobie itch.”

Pemphigus Acutus Neonatorum1 (Pemphigus neonatorum; Pem-

1 Literature bearing upon pemphigus neonatorum, pemphigus epidemicus, and

pemphigus contagiosus: Staub, “Ueber den Pemphigus der neugeborenen und der

Wöcherinnen,” Bericht des II. Intemat, Dermatolog. Congress, 1892, p. 699; Strelitz,

“Bacteriologische Untersuchungen über den Pemphigus neonatorum,” Archiv für Kin

derheilkunde, 1890, vol. xi, p. 7; and 1893, vol. xv, p. 101; Peter, “Zur Aetiologie des

Pemphigus neonatorum,” Berlin klin. Wochenschr., 1896, p. 124 (in infant suckled by

septicemic mother); Zechmeister, “Ueber Pemphigus neonatorum,” Münchener med.

Wochenschr., 1887, p. 737—abstract in Archiv, 1888, p. 271 (in 76 births under charge

of one midwife 28 cases developed, of which 6 were fatal); Wichmann, “Epidemie von

Pemphigus Contagiosus,” Tidsskrift für praktisk Medicin, 1887, No. 21—abstract in

Archiv, 1888, p. 423 (in the newborn; 23 cases, of which 3 died—all the children born

under the care of the same midwife); Jükovsky, “Pemphigus neonatorum," Vratch,

No. 15, 1891, p. 357—abstract in Brit. Jour. Derm., 1891, p. 368 (12 infants, of which

4 died—all born under care of same midwife); Kilham, “An Epidemic of Pemphigus

PEMPHIGUS

375

phigus neonatorum contagiosus; Pemphigus epidemicus; Pemphigus

contagiosus).—The cases usually included under this subheading of

acute pemphigus, and formerly believed, and still believed by a few

observers, to represent a distinct pemphigus type, are those observed

a few days after birth, many of which run a short, mild course, others

going on to a rapidly fatal termination. Almost all, and probably

all, these cases, as Richter‘s analytical study and later observations

Neonatorum,” Amer. Jour, of Obstet., 1889, p. 1039 (12.cases, all mild; bacteriologic

examination negative); Homolle, “Epidemic of Acute Pemphigus in the New-born,”

Gazette Hebdom., Nov. 13, 1874—abstract in Arch. Derm., 1875, p. 154 (among 79

births but few escaped; the disease was mild, but 1 case ending fatally; inocu

lation experiments negative); Corlett, Indiana Med. Jour., Nov., 1893, p. 158;

Moldenhauer, “Ein Beitrag zur Lehre vom Pemphigus acutus,” Archiv für Gynäkol.,

1874, vol. vi, p. 369 (101 cases observed in a period of about a year—mild, and dis

tribution, character, and behavior indicate that they were cases of impetigo conta-

giosa); Klemm, “Zur Kenntniss des Pemphigus contagiosus,” Deutsches Archiv für

klin. Medicin, 1871, vol. ix, p. 199 (28 cases are reported, and a study of which leaves

but little doubt that they were examples of impetigo contagiosa); Faber, “Ueber den

acuten contagiösen Pemphigus,” Monatshefte, 1890, vol. x, p. 253 (an analytic paper

of reported cases, indicating the probability that many were impetigo contagiosa);

Greer, “Puerperal Septicemia and Pemphigus Neonatorum,” Brit. Med. Jour., 1894,

i, p. 1241; Holt, “Pemphigus Neonatorum” (1 case associated with general infection

with staphylococcus pyogenes; death), N. Y. Med. Jour., 1898, i, p. 175; Solbrig,

“Pemphigus neonatorum,” Zeitschrift für Med.-Beamte, 1900, vol. xiii, p. 41; Köhler,

“Ueber die Diagnose und Pathogenese akuter Blasenbildung der Haut nebst kasuis-

tischem Beitrag zur ‘Febris bullosa’" (small epidemic of 7 cases, 1 of which died),

Deutsches Archiv für klin. Medicin, 1899, vol. lxii, p. 579; Bernstein, “Ein Beitrag

zur Kenntniss des Pemphigus neonatorum acutus” (5 cases, infants and adult; some

what suggestive of impetigo contagiosa, although the reporter excludes this, and ex

perimental inoculations were negative), Monatshefte, 1899, vol. xxviii, p. 19; Bloch,

“Pemphigus neonatorum,” Archiv für Kinderheilk., 1900, vol. xxviii, p. 61 (an obser

vation of 20 cases, some fatal; clinical, anatomic, and bacteriologic aspects are pre

sented); Knocker, “Pemphigus Neonatorum” (2 cases, mild in type; had been de

livered and looked after by the same nurse), Brit. Jour. Derm., 1898, p. 195; Beck,

“Aetiologie des Pemphigus neonatorum” (1 case—death; cocci, usually paired, found

in lesions and blood)—abstract in Monatshefte, 1899, vol. xxviii, p. 410; Windisch,

“Pemphigus Contagiosus Tropicus,” Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, 1900, vol. xxxiv, p. 77;

Munro, “Pemphigus Contagiosus (tropicus),” Brit. Med. Jour., April 29, 1899, P. 1021;

Finlay, “Pemphigus Contagiosus Tropicus,” Austral. Med. Gaz., 1898, p. 114; Brosin,

“Pemphigusübertragungen im Wirkungskreise einzelner Hebammen” (2 epidemics; in

a total of 64 confinements 18 cases, 7 of which died), Zeitschrift für Geburtshülfe und

Gynäkologie, 1899, vol. xl, p. 418; P. Richter, “Ueber Pemphigus neonatorum,” Derma-

tolog. Zeitschr., 1901, vol. viii, Nos. 5 and 6, reviews most thoroughly the whole subject

(over 100 pages, with 20 pages of references); he concludes that the dermatitis exfolia-

tiva neonatorum of Ritter is a variety, and that pemphigus neonatorum also bears a

relation to impetigo contagiosa, the characters of the newborn skin being responsible

for the clinical differences; it is due to the presence of a staphylococcus of a doubtful

nature, with a group, more malignant, infected with streptococci or mixed staphylo-

cocci and streptococci. G. J. Maguire, “Acute Contagious Pemphigus in the New-

born,” Brit. Jour. Derm., 1903, p. 427 (indicative of its identity or allied nature to

bullous impetigo contagipsa); Adamson, “Pemphigus Neonatorum in the Light of

Recent Research,” ibid., p. 447 (conclusion as to its being an infantile form of impetigo

contagiosa); Crary, “A Case of Acute Septic Pemphigus,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1906, p.

14 (with review and bibliography); Schwartz (Geo. T. Elliot‘s Service), “An Epidemic

of Pemphigus Neonatorum,” Bull, of Lying-in Hosp. of New York, June, 1908 (with

case and histologic illustration; there were 27 cases in all, 22 of the 27 developing be

tween the fourth and seventh day; 7 died and most of these died on the fourth to tenth

day of the disease; cultures from blebs, before and after death, showed only a staphy-

lococcus; there was distinct evidence of the contagious nature of the disease; the mild

cases, running a benign course, would have been looked upon, the writer states, as

impetigo contagiosa; Foerster, “Pemphigus Neonatorum, or Bullous Impetigo Con-

tagiosa of the New-born,” Jour: Amer. Med. Assoc, 1909, vol. liii, p. 358 (review, with

literature references).

376

INFLAMMATIONS

by others indicate, should be viewed as probably a type, possibly a

variant or contaminated type, of bullous impetigo contagiosa.1 Two

forms are usually distinguished, the grave type, which sometimes re

sembles pemphigus foliaceus and Ritter‘s disease, and a mild or benign

form. The mild type, of which a number of instances have been re

corded (01shausen and Mekus, Ravogli, Corlett, Kilham, Padosa,

Crocker, Knocker, and others), is usually entirely free from systemic

Fig. 90.—Acute pemphigus, with bleb walls largely rubbed off or collapsed;

simulated the lesions of an impetigo contagiosa in the earliest part; in some places

patches becoming larger by a spreading undermining serous exudation; lesions were

almost all more or less flaccid and flat; fatal ending.

disturbance, is of acute onset, and is seen in the newborn, usually in

the first several days of life. The lesions are, as a rule, not very numer

ous, and while they may be seated upon any part, are observed most

frequently or abundantly about the lower trunk and thighs. The

eruption may however, be quite extensive and of general distribution.

A favorable termination is reached in the course of a few weeks.

1 It is not improbable that even dermatitis exfoliativa neonatorum might be very

properly viewed in the same light.

PEMPHIGUS 377

On the other hand, cases are reported (Tilbury Fox, Staub, Peter,

Greer, Moldenhauer, Klemm, Brosin, and others) of severe and grave

characters. The eruption may be somewhat sparse or abundant, and

there is accompanying febrile action as observed in ordinary acute

pemphigus cases already described, with septic symptoms; or there

may be practically absence of fever, and yet the cases terminate fatally

(Brosin).

Pemphigus Chronicus.—Under chronic pemphigus belong most of

the cases usually met with, and to which the name of pemphigus vulgaris

is also applicable. It is, like other varieties, rare, and especially

in this country. Its chief distinction from the others is that the blebs

continue to appear incessantly, the skin being, as a rule, never free.

On the other hand, there may be shorter or longer intervals of compara

tive or complete freedom. The lesions appear irregularly, one or several

at a time, or there are distinct crop-like exacerbations, the blebs appear

ing in numbers. Probably most commonly they make their appearance

in numbers for several days or more; these subside, crust over, and dis

appear, during which time and for a few weeks or longer scattered lesions,

in scanty number, arise, and then another moderate or extensive out

break manifests itself, and so the malady continues indefinitely. The

mouth and throat in occasional cases are also noted to exhibit the erup

tion, and exceptionally the disease may have its beginning in these parts.

In rare instances the conjunctivæ (pemphigus conjunctivæ) are also

invaded, and sometimes accompanied by shrinking of the parts (von

Graefe, Morris and Roberts, Fuchs, and others) ,1 The blebs are usually

well distended, pea- to small egg-sized, scattered, or often close together,

several occasionally coalescing, although there is but little tendency

to grouping. A slight admixture of blood is sometimes noted, and

in exceptional cases this may be quite decided (pemphigus hæmorrhagi-

cus). An individual lesion, as in the other varieties, runs its course,

and crusts over in several days to two weeks. No permanent trace

is left by the eruption, but on areas frequently covered with recur

rent lesions slight pigmentation may show itself. In the mild cases

there are no constitutional symptoms; in others chilliness and febrile

action preceding or accompanying the original outbreak, subsiding

and again presenting at the time of the exacerbations; in still others

of the more extensive type the systemic disturbance is more or less

continuous. The subjective symptoms of burning, soreness, and

itching (pemphigus pruriginosus) may be present in variable degree;

itching is rarely troublesome and often absent. The disease may

finally end in recovery or terminate fatally, its course being usually

long and indeterminate.

1 Morris and Roberts, “Pemphigus of the Skin and Mucous Membrane of the

Mouth, Associated with ‘Essential Shrinking’ and Pemphigus of the Conjunctivæ,”

Brit. Jour. Derm., 1889, p. 176, and Monaishefte, 1889, vol. viii, p. 437 (a report of a

case, with colored plate, and a tabulation and references of 28 previously reported

cases); Meneau, Jour. mal. Cutan., Jan., 1905, gives an extensive review of different

forms of pemphigus as involving the mucous membrane, especially of the conjunctiva,

nose, mouth, throat, and larynx (with complete bibliography); Cocks, Jour. Amer.

Med. Assoc, Nov. 24, 1906, p. 1736, records a fatal case in which the eruption was

limited to the mucous membranes.

378

INFLAMMATIONS

Pemphigus Foliaceus.1—This variety, which is extremely rare, may

assume its peculiar features from the start or it may develop from an

acute or chronic pemphigus of the ordinary character; in other in

stances it has begun as a superficial generalized cutaneous edema

(Quinquard), as a scaly greasy surface (Besnier), as a dermatitis her-

petiformis (Hallopeau and Fournier). It is characterized by the

formation of blebs so rapidly and so quickly repeated that the dis

tended bulla is not seen. It is flat and but slightly raised, and is scarcely

dried to a crust before another flaccid lesion forms beneath. Or the

blebs appear, but instead of being distended and elevated, are flaccid

and flat, become purulent, break or are accidentally ruptured, and

then a gradual undermining of the surrounding epidermis is noted.

The eruption is usually abundant and generally distributed, and may,

1 Literature of pemphigus foliaceus: Nikolsky, “Contribution a la question du pem

phigus foliacé de Cazenave,” Thèse de doctorat, Kieff, 1896 (refers cases of Cazenave,

Plieninger, Bazin, Guibout, Meyer, Munro and Swarts, Sormani, Besnier (2 cases),

Hallopeau and Fournier (3 cases), Petrini (3 cases), Regensburger, and Dumesnil de

Rochemont—17 cases in all); Lausac, “Du pemphigus foliacé mixte primitif,” Thèse de

doctorat, Toulouse, 1898 (reports 1 case and refers to 28 cases previously observed by

others—brief abstract of his own case and conclusions in Annales, 1898, p. 1040;

Biddle, “Pemphigus foliaceous or Dermatitis herpetiformis,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1897,

p. 203; Sherwell (1 case, with photo), Arch. Derm., 1877, P. 97, and (same case—recov

ery and relapse), Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1889, p. 453; Graham (1 case), Canadian Jour.

Med. Sci., June, 1879; Hardaway (1 case), Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1890, p. 22; Munro and

Swarts’ case (ibid., 1891, pp. 332 and 423), already named in Nikolsky‘s paper, seems

to partake of the nature of both pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vegetans; Klotz

(1 case), Amer. Jour. Med. Sci., Dec, 1891; Nasarow (1 case), Dermatolog. Zeitschr.,

1899, vol. vi, p. 719; Nazaroff (1 case), Roussky Archive Patologgi, Feb., 1900—abstract

in Brit. Jour. Derm., 1900, p. 258; Hellier (1 case—infant (pemphigus neonatorum?),

Brit. Journ. Derm., 1899, p. 18; Savine (1 case), Jour, de med mil. russe, July, 1897;

abstract in Annales, 1898, p. 597; Hallopeau et Constensoux (1 case with associated

osteomalacia), Annales, 1898, p. 979; Lindstroem (3 cases), ibid., 1898, p. 1026; Leredde,

“Etude sur le pemphigus foliacé de Cazenave,” ibid., 1899, p. 601 (a study of path

ology and pathologic anatomy, with some literature references); Fabry, Archiv, June,

1904, p. 183 (1 case, beginning with redness and scaling, showing at first a suggestive re

semblance to pityriasis rosea and eczema marginatum developing into pemphigus

foliaceus); Brousse and Bruc, Annales, 1905, p. 853 (1 case; began with an erythematous

eruption, intense general itching, followed by bleb formation, which became generalized,

and in a month had developed into the exfoliative type; autopsy report and 1 clinical

and 1 histologic illustration); R. Cranston Low, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1909, pp. 101 and

135 (2 cases, both women; a third case, with symptoms of both dermatitis herpeti-

formis and pemphigus foliaceus; good review of the subject, discussion of a suggestive

occasional relationship with dermatitis herpetiformis and full bibliography; several

case illustrations); ibid., 1911, p. 1, a fourth case, woman aged fifty-two, of two years’

duration, at first diagnosed as dermatitis herpetiformis; out of 3 cases only 1 (the

last) gave a culture of the bacillus pyocyaneus; of the previous cases, case 1, the skin

condition still remains in statu quo; the case 3 has remained fairly well, but has

occasional recurrences of an eruption of the nature of dermatitis herpetiformis; Scha-

lek, Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, July 2, 1910—male, aged thirty-six; C. J. White, Boston

Med. and Surg. Jour., May 4, 1911 (case report—female aged seventy-three, death nine

to ten months after original outbreak); Hazen, “Pemphigus Foliaceus,” Jour. Cutan.

Dis., 1910, p. 118; male, Hebrew aged thirty; had begun about year before coming

under observation; bacillus pyocyaneus was demonstrated in circulating blood, urine,

and non-purulent vesicles, and over the entire cutaneous surface; staphylococcus was

a secondary invader; and ibid., 1912, p. 325, second case in negro woman, aged fifty-

one, dying about five months after its first appearance; cultures from the blood, from

the skin at large, and from the outside of the vesicles, from old vesicles, and from

ruptured vesicles, gave the staphylococcus albus; cultures from fresh, unruptured

vesicles always gave bacillus pyocyaneus in pure culture; autopsy; cultures were

made from the heart’s blood, liver, spleen, and kidneys, and all gave a pure growth

of the bacillus pyocyaneus; histologic illustrations and bibliography.

PEMPHIGUS

379

indeed, involve almost the entire surface. In the latter instances a pic

ture is presented of extremely flaccid, scarcely elevated, seropurulent

or purulent variously sized blebs, with the fluid bulging them out at the

most dependent portion; ruptured lesions with a serous or seropurulent

undermining of the immediate surrounding epidermis; thin crusts with

rapidly forming exudation beneath, and large red, raw, oozing sur

faces where the crusts have been removed or rubbed off, and where

the exudation is so rapid that a new crust cannot form. Exception

ally the surface remains, temporarily at least, almost dry, the condi

tion resembling dermatitis exfoliativa. Fissuring occurs, especially

about the joints, and there is a pervading foul odor about the patient.

In extreme cases the nails and hair are brittle and sometimes shed,

the eyes are sore-looking, the conjunctivæ may become involved, the

mucous membranes share in the disease, and with increasing gravity

of the constitutional symptoms, and, in a majority of the cases, the

patient finally succumbs from exhaustion, pyemia, or from some inter-

current disease. Exceptionally there are long intervals of freedom

(Sherwell). The malady is rare, but there has been a gradual addition

to the number of reported cases since the disease was first described

(Cazenave, 1850); in this country cases have been recorded by Sherwell,

Graham, Hardaway, Klotz, Munro and Swarts, Hazen, C. J. White, and

a few others.

Pemphigus Vegetans.1—This variety, also called erythema bullosum

1 Literature of pemphigus vegetans: Crocker, “Pemphigus vegetans (Neumann),”

Brit. Med. Jour., March 16, 1889, and London Med.-Chirur. Soc‘y Trans., 1889, vol.

lxxii, p. 233 (a bibliography of cases to date is given); Mapother (1 case), ibid, (re

ferred to in the discussion); Müller, Monatshefte, 1890, vol. xi, p. 427 (2 cases, with

2 plates presenting 4 histologic cuts; a brief review of 22 other cases from literature,

with references, are given); Hyde (1 case), Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1891, vol. ix, pp. 412

and 459; Lowe, Lancet, May 23, 1891; Haslund, Hospitalstidende, 1891 (quoted by

Crocker); Herxheimer (3 cases, “Festschrift der Städtischen Krankenhauses in Frank

furt A. M.,” Archiv, 1896, vol. xxxvi, p. 141; Köbner (2 cases), Deutsches Archiv für klin.

Medicin, vol. liii, and vol. lvii, abstracts in Annales, 1894, p. 890, and 1897, p. 816;

Luithlen, “Pemphigus vulgaris et vegetans,” Archiv, 1897, vol. xl, p. 682; Tommasoli,

Archiv, 1898, vol. xliv, p. 325; Neumann, Wien. klin. Rundschau, 1900, No. 1, p. 1;

Pini, Giorn. ital., 1898, p. 354 (chemical experimental researches)—brief abstract in

Annales, 1899, p. 505; Phillipson, et Filed (1 case), Giorn. ital., 1896, p. 354; Ludwig

(1 case), Deutsch. med. Wochenschr., 1897, p. 267; Mracek (1 case), abstract in Annales,

1898, p. 919; Duhring (1 case), Cutaneous Medicine, part ii, p. 456; Zumbusch, “Ueber

Zwei Fälle von Pemphigus Vegetans mit Entwicklung von Tumoren,” Archiv, 1904,

vol. lxxiii, p. 121 (mild course with pedunculated papillomatous growths in 1 case;

large areas of papillomatous development in 1 case on forearms, leg, and soles of feet

(Dermatitis vegetans (?)); Jamieson and Welsh, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1902, p. 287, and

Dyce Duckworth, ibid., 1903, p. 26, and 1904, p. 245 (histologic report by Little, ibid.,

p. 138), each reports an extensive case—both fatal; Hamburger and Rubel, Johns Hop

kins Hosp. Bull., April, 1903, p. 63, report a fatal case, and review the literature; Zum-

busch, Archiv, 1905, vol. xliii (2 cases with development of tumors, 2 colored plates);

Ormsby and Bassoe (an acute fatal case with autopsy), Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1905, p. 294;

Ravogli, ibid., 1906, p. 311; Winfield, ibid., 1907, pp. 17 and 71 (with illustration), re

ports a fatal case with autopsy, and gives a brief analytic review of reported cases with

references; Constantin, Annales, 1907, p. 641 (case with features of dermatitis herpeti-

formis and pemphigus vegetans); W. Fox, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1908, p. 181 (case with

illustration of vegetations in axillae developing upon an ordinary pemphigus, vegetating

tendency subsequently disappearing, the malady assuming the type of a somewhat

mild pemphigus); MacCormac, ibid., p. 277 (vesicles appearing nine days after child

bed, first about the genitalia; later, vesicles and bullæ becoming more general, the

vegetating tendency about axillae and lower abdomen; death in three and one-half

months—references as to bactiorologic findings) Pernet, “Pemphigus Vegetans and

38o

INFLAMMATIONS

vegetans (Unna) is the rarest of all, and was first described (Neumann)

in 1886; since then other cases have been reported (Crocker, Hyde,

Haslund, Hutchinson, Riehl, Duhring, and others). The earliest

manifestations are usually to be seen in the mouth, throat, or lips, and

consist of whitish or reddish plaques; soon the ordinary blebs appear

on the integument, and these may at first maintain the character of

ordinary pemphigus, but after a while, instead of going through the

crusting and disappearance, as usually noted, vesicles or blebs form

around a crust; the base of such a patch becomes inflamed, often edem-

atous, covered with a viscid, offensive secretion, and finally exhibits

papillomatous or condyloma-like vegetations. Several such plaques

become confluent and form large areas. This peculiar development is

seen most commonly about warm and moist surfaces in close contact,

as about the genital, anal, and axillary regions. With increasing

constitutional symptoms which are usually present from the beginning,

the disease, with rare exceptions, finally ends fatally. In favorable

cases the process gradually declines; these seem to be chiefly those

in which the eruption was scanty and mainly about the mouth (Hutch-

inson). The malady is sometimes variable in its course, and occasionally

presents here and there distinct blebs in which the vegetating tendency

is not displayed. Exceptionally there is observed a combination of

its own peculiar manifestations with the symptoms of pemphigus

foliaceus. There is usually temperature elevation, somewhat variable,

it is true, determined by the extent and gravity of the disease; it is

usually more marked at periods of exacerbation of the cutaneous

phenomena. On the other hand, the body-heat is noted at times to be

below normal.

Etiology.—Pemphigus is, fortunately, extremely rare, and much

more so in this country than in Europe. It is met with in both sexes,

with probably a slight preponderance in females; it is more frequent

in infants and children than in adults. The causes are obscure. It is

not due to syphilis, although this latter does give rise to a pemphigoid

eruption, but one entirely different in its character, course, and behavior.

It is not hereditary; the cases of hereditary tendency to bullous develop

ment upon the slightest local irritation belong to epidermolysis bullosa

(q. v.). It is probable that the several so-called varieties are due to dif

ferent causes, or at the least the ingrafting of an accidental factor upon

the same disease process. Acute pemphigus sometimes has its origin

in a septic wound (Pernet and Bulloch, Hadley and Bulloch); from, in

infants, a disease of the navel and from puerperal processes in the mother

(Staub, Peter, Greer). Pernet and Bulloch's studies, as well as such

cases as that reported by Bowen, point strongly toward animals or their

the Bacillus Pyocyaneus,” Brit. Med. Jour., October 15, 1904 (1 case) and “A Case of

Pemphigus Vegetans, ibid., Sept. 24, 1910 (1 case); Pollitzer, “Pemphigus Vegetans”

(starting as a condylomatous patch at anus in male aged fifty-nine—death in about six

months), Festschrift zur Vierzigjährigen Stiftungsfeier der Deutschen Hospitals, New

York, 1911, p. 546; abstract in Brit. Jour. Derm., 1911, p. 335; Rutherford, Brit. Jour.

Derm., 1910, p. 118 (1 case—acute, death in seventeen weeks); Hartzell, “A Case of

Pemphigus Vegetans, with Special Reference to the Cellular Elements Found in the

Lesions,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1910, p. III. Bottelli, Giorn. ital., full abstract in Brit.

Jour. Derm., 1911, p. 371, began during pregnancy; bacteriology negative; death.

PEMPHIGUS 38l

products as a frequent source; this may, too, explain the cases following

vaccination occasionally, as, for instance, Howe's cases. Bowen calls

attention to the similarity of some cases of “foot and mouth disease”

in cattle to acute pemphigus in man. Doubtless, in many of these

acute cases just referred to, the actual underlying factor is a strepto-

coccic infection. The bacillus pyocyaneus has also been credited with

being the cause in some cases.1 Johnston2 believes we have evidence of

the existence of an autotoxic factor in the production of pemphigus and

other bullous diseases, a view which, it seems to me, has much in its

favor, but this autotoxic factor may be of varying nature and origin.

Other factors which seem to be of moment in the production of the dis

ease are chills (Schwimmer, Crocker), nervous influences, such as periph

eral nerve injuries (Mitchell, Morehouse and Keen, Mougeot, Leloir),

diseases of central nervous system (Charcot, Balmer, Leloir, Kopp,

Schwimmer, Brissaud, and others), degenerative changes in the periph

eral nerves and nerve-centers (Déjerine, Quinquaud, Jarisch, Mott and

Sangster, and others), functional nervous disturbance, and hysteria—

pemphigus hystericus3 (Kaposi, Hardy, Jarisch, Duhring, and others).

Against these evidences must, however, be quoted the observation

(Kaposi and Weiss) that in 9 fatal cases, in only 1 was there structural

nerve alteration—diffuse sclerosis of cord.

That the derangement, functional or organic, of the nervous system

is of etiologic importance is borne out by the cases reported by the

writers just referred to, and by the experience of almost all others

who have to do with this disease. Whether the action is a direct one

or merely contributory to a successful parasitic invasion or infection is

an unsolved question. At all events, whatever the rôle of the nervous

system may be in the chronic variety, there can scarcely be a doubt

that an important etiologic factor in many of the acute cases, and

especially those in infants and young children, particularly those of

epidemic and contagious character, is to be found in micro-organisms.

Such findings have been recorded by a number of observers (Alm-

quist, Escherich, Peter, Luithlen, Gibier, Demme, Sahli, Claessen,

Whipham, Holt, Beck,4 and others), but there has not been sufficient

1 Petges and Bichelonne, “Septicémie a bacille pyocanique et pemphigus bulleux

chronique vrai,” Annales, 1909, p. 417, report a case, review the subject, with refer

ences, and conclude that the bacillus pyocaneus can play a rôle both in chronic bullous

pemphigus and pemphigus vegetans; Hazen (loc. cit.) found this organism in two cases

of pemphigus foliaceus and believes it pathogenic in some cases.

2 Johnston, Brit. Med. Jour., Oct. 6, 1906.

3 C. J. White, “Recurrent, Progressive, Bullous Dermatitis in a Hysterical Subject,”

Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1903, p. 415, reports a curious case of bullous lesions, the outbreak

beginning usually on an extremity, and then extending upward, with periods of freedom,

and later involvement of other parts (4 other somewhat similar cases in literature are

briefly described, with references to these and other papers on allied subjects). Coffin,

Boston Med. and Surg. Jour., April 27, 1911, p. 612, gives details of a case—patient,

woman aged fifty-seven—in which oral cavity, epiglottis, and larynx were involved for

four years without accompanying cutaneous manifestations: two years after the onset

the eyes became involved; and two years later the skin became involved for the first

time, and one year before her death (five years after beginning), blebs appeared over

entire body; death from sepsis starting in a lesion on the foot.

4 Lipschütz, Archiv, 1912, cxi, No. 3, p. 675—abstract in Jour. Cutan. Dis., March,

1913, (elaborate study based on 11 cases of chronic pemphigus) has found two distinct

parasites in the serum contents of the bullæ; one he names the “cystoplasma oviforme,”

382 INFLAMMATIONS

uniformity to warrant positive conclusions, although the majority of

observers found, in pemphigus neonatorum,1 staphylococcus aureus

and albus; and some were able to produce the disease by inoculation

from lesions (Moldenhauer, Koch, Vidal), and also by inoculation from

cultures (Almquist, Strelitz). A diplococcus has been found by several

observers in acute pemphigus (Demme, Claessen, Bulloch, Whipham,

Beck). Investigations by others in both these directions have, how

ever, not met with the same positive results. The acute cases resulting

from septic infection already referred to point likewise to micro-organ

isms as a cause. The microbic view is also supported by the series of

cases of pemphigus neonatorum occurring in infants cared for by the

same widwife, an observation repeatedly made (Corlett, Knocker, and

several others). It is probable that most of these are examples of

bullous impetigo contagiosa, as instances of transference to older mem

bers of the family, etc., have occurred, and in whom the lesions are

essentially those of this latter disease, a view which is held by most

observers (Pontoppidan, Faber, Crocker, Duhring, and many others).

Another view of the etiology of pemphigus formerly held was that

the malady is due to defective kidney elimination, and occasional acute

cases are noted to follow or be associated with organic kidney disease.

Urine examinations in most instances, however, disclose nothing. As

in other bullous diseases, eosinophilia has been noted (Leredde), and a

diminution of the red blood-corpuscles observed (Hallopeau and Leredde,

Nikolski).

Pemphigus, especially the acute form, has also been observed to

follow rheumatic fever, the exanthemata, diphtheria, and other acute

systemic disorders.

Pemphigus vegetans2 seems, as noted by Hutchinson, Danlos, Brocq,

and others, much more common with those who live in the country—

2 cases that came under my observation were from country districts.

Pathology.—In connection with pemphigus lesions on the skin

organic changes have been noted, as already remarked, in other struc

tures, more especially the nervous system in its various parts, centrally

to peripherally,3 the liver and kidneys have also exhibited disease in

measuring 1.5 to 2.7 micra, with an eccentric nucleus, extending through the margin

or just bordering the periphery; in the same case it may be absent at times and times

when present in great numbers; the other organism, he names “anaplasma liberum,”

is considerably smaller, has practically no cytoplasm, being entirely made up of

chromatin or nuclear substance. The exact relationship of the two is not clear. He

found the same present in cases which pass as dermatitis herpetiformis.

1 Both Whitfield (Brit. Jour. Derm., 1903, p. 221) and Macleod (Brit. Med. Jour.,

1903, p. 1278) obtained pure cultures of a streptococcus.

2 Stanziale, Annales, 1904, p. 15, found in a case of pemphigus vegetans a diplo-

bacillus (probably identical with the small diplococcus of Waelsch), and a pseudo-

diphtheritic bacillus. The latter, he thought, played a rôle in the production of the

vegetating lesions. Hamburger and Rubel, loc. cit., also isolated: a pseudodiphtheritic

bacillus.

3 Jamieson and Welsh, loc. cit., found in a well-marked case of pemphigus vegetans

distinct degenerative changes of a special character in the nerve-cells of the spinal cord,

and to a less pronounced extent of the sympathetic ganglia, and the cerebral cortex; con

sisting “of an evidently slowly progressive rarefaction of the chromophile bodies of the

protoplasm, more especially in the perinuclear zone, formation of minute vacuoles in

the altered portion of the protoplasm, swelling of the cell-body, disintegration of the

nucleus, and, finally, destruction of the whole element.”

PEMPHIGUS

383

some cases. To a great extent, or at least in many instances, the

cutaneous manifestations must be considered but a part of a systemic

process or infection. This belief is supported by the findings of micro-

organisms referred to in etiology.

Pathologic anatomy1 discloses (Robinson, Crocker, Luithlen, Unna,

Gilchrist, Jarisch, and others) that the local changes in the cutaneous

lesions are slightly varied, dependent, doubtless, upon the degree of

inflammatory action and the stage of formation, although the bleb is

more superficial than obtains in herpes. The roof-wall is the upper

horny layer, and the base the rete; but in some instances the inside of

the roof shows a layer of rete cells, and in others the corium is the floor

of the lesion. The bleb is doubtless due to a sudden effusion from the

vessels of the corium, probably following paralysis and dilatation of the

vessels.2 In the early stage of its formation, in most lesions, inflamma

tory signs are slight; in others they are present, usually but to a moderate

degree. The papillae are edematous; dilatation of the vessels, emigration

of polynuclear leukocytes, and a variable amount of serous infiltration

of the tissues are noted. In pemphigus vegetans are found (Neumann,

Riehl, Kaposi, Unna3) marked hypertrophy of the papillae and pro

nounced proliferation of the rete, with outgrowth of the same; enlarge

ment of the superficial blood-vessels and edema of the upper layers of

the corium.

The contents of the lesions are neutral or alkaline in reaction and

composed of serum, to which are added later pus-cells, epithelial cells,

and fat; ammonia has been found in it, as well as in the urine; phos

phorus has also been found and thought to be due to nerve dis

integration. An increase of eosinophile cells has, as already stated,

in some instances been noted both in the bullæ and in the blood,

but as yet no significance can be assigned to this increase, as it is

observed in vesicles and bullæ of other maladies and even in those of

artificial origin.4

1 Jarisch, “Zur Anatomie und Pathogenese der Pemphigusblasen," Archiv, 1898,

vol. xliii, p. 341; Robinson, section, drawing, and description in Duhring's Cutaneous

Medicine, part ii; Gilchrist, ibid.; Kromayer, Dermatologische Zeitschrift, 1897, vol.

iv; Kreibich, Archiv, 1899, vol. 1, pp. 299, 375; Luithlen (Pemphigus vulg. et veg.),

Archiv, 1897, vol. xl, p. 682, and (Pemphigus neonatorum), Wien. klin. Wochenschr.,

1899, p. 69.

2 According to Weidenfeld‘s investigations (“Beiträge zur Klinik und Pathogenese

des Pemphigus,” Vienna, 1904, a monograph based on 18 cases: 9 pemphigus vulgaris,

4 pemphigus serpiginosus, 5 pemphigus foliaceus, and 1 pemphigus vegetans), he found

that in some cases of pemphigus, pressure would always provoke a bleb, in other cases

pressure had absolutely no influence, while in a third group it was variable—sometimes

pressure producing a bleb and sometimes not. In the stages of improvement none could

be provoked, but as soon as the general condition (eruption, etc) showed increase and

aggravation, blebs could again be provoked by pressure. The author explains this upon

the assumption of a variation or disappearance and reappearance of some noxious mate

rial having a damaging influence on the circulatory system.

3 Hartzell (loc. at.) found in a flaccid bleb from a case of pemphigus vegetans in

addition to eosinophiles, “a moderate number of large round cells quite uniform in size

and appearance, lying here and there among the other cells, stained with eosin, con

taining a large cavity with a limiting membrane more deeply stained than the ring-

like body of the cell.” They resembled the “ballooned” epithelium found in zoster,

etc, although the writer inclined to believe them quite distinct.

4 Hartzell found the eosinophiles extremely numerous in a bleb of pemphigus vege-

tans and scanty in number in a bleb from pemphigus vulgaris.

384

INFLAMMATIONS

Diagnosis.—The disease is to be distinguished from erythema

bullosum, urticaria bullosa, impetigo contagiosa, dermatitis herpeti-

formis, and the bullous syphiloderm.

In erythema bullosum the blebs are a part of an eruption (ery

thema multiforme) in which other characteristic features are usually

present; even when all the lesions are bullous there is likely to be a

circinate or ring-like configuration with some, and the eruption is gen

erally limited to, or more abundant on, certain regions, as the hands

and forearms—erythema bullosum never has a general distribution.

Moreover, the blebs frequently spring from erythematous or inflam

matory skin, and the disease runs a rapid course without, as a rule,

any persistent or marked systemic symptoms.

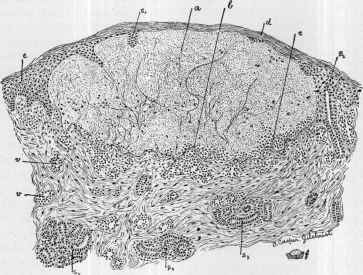

Fig. 91.—Pemphigus—a beginning bleb (a) between corium and the epidermis,

the bared papillæ (b) forming the base; acute inflammatory changes in the papillary

layer of the corium, with marked serous exudation, particularly about the vessels;

reticular part of the corium and the sweat-glands (s3, s4, s5) are practically normal,

except where the sweat-ducts (s1, s2) are involved in the bleb-formation: d, corneous

layer; e, rete; v, v, blood-vessels; c, cell masses at base;f, about the natural size of bleb

examined (courtesy of Dr. T. Caspar Gilchrist),

The bullous syphiloderm is usually observed in infants in the first

few days or weeks of life; and the lesions are often seen on the palms

and soles, parts not commonly involved in pemphigus. Moreover,

the syphilitic blebs soon become puriform, form thick crusts, and

under which, as a rule, ulceration is noted. In syphilis of this type

other characteristic symptoms are always to be found. Pemphigus

vegetans bears strong resemblance to the vegetating syphiloderm; in

this latter, however, the disease remains more or less limited to the

genital region and around the anus, with but little disposition to spread

extensively, as is observed in pemphigus. Moreover, in syphilis a

positive destructive tendency is sometimes noted, and there is absence

PEMPHIGUS

385

of any tendency to bleb-formation, usually seen at some stage of pem

phigus vegetans. The clinical history, the presence or absence of other

syphilitic lesions or symptoms, examination for spirochætæ, and the

Wassermann test must sometimes be utilized. In pemphigus, too,

slight or severe constitutional involvement is usually noted. Pem

phigus foliaceus and dermatitis exfoliativa are sometimes confounded,

but the dry character in the latter and the absence of mouth involve

ment and any tendency to bleb-formation are different from what are

observed in pemphigus.

Eczema rubrum and pemphigus foliaceus have, in a general way,

some resemblance, but the former is never universal, and, indeed,

rarely extensive; the crusting of the former is usually less pronounced,

the crusts being in small flakes, whereas in pemphigus they are often

of considerable size; moreover, blebs are not seen in eczema, and the char

acters of the general symptoms observed in pemphigus are wanting.

It is scarcely possible to confound the blebs occasionally noted in

scabies with pemphigus; in the former there is never present more than

a scant number, and the other eruptive lesions, together with the dis

tribution and history, are entirely different from the picture of pemphi

gus. The differentiation from bullous urticaria, impetigo contagiosa,

and dermatitis herpetiformis will be found discussed under those diseases.

Prognosis.—Too much caution cannot be exercised in express

ing a positive opinion as to the final outcome. As to acute pemphi

gus, the character of the outbreak, whether attended by active con

stitutional symptoms, the behavior of the lesions (whether serous,

purulent, hemorrhagic, or gangrenous), the extent of the eruption,

the previous and present health of the patient—all have a bearing.

Those cases in which more or less grave systemic disturbance presents,

and those, usually the same class, in which the lesions become rapidly

purulent or are hemorrhagic or gangrenous, are almost always fatal.

Involvement of the mucous surfaces is of unfavorable significance.1

Even slight systemic disturbance, especially chills, has a serious import.

The vegetating and foliaceous varieties rarely recover, but they may be

of months’ or years’ duration. The septic types, arising from a wound,

are grave. Almost all cases unattended by temperature elevation or

other constitutional symptoms get well, although the possibility of chang

ing to a severe type is to be kept in mind. In short, the prognosis for

the milder cases is usually favorable; for the extensive and grave erup

tions, serious. The prospect in children is much better than in adults.

In chronic cases the same features bear upon the ultimate prog

nosis: persistence and chronicity are the rule, and relapses are not un

common. Death usually takes place from general septic infection;

from gradual marasmus, sometimes with diarrhea; and occasionally

from sudden collapse.2

Treatment.—The treatment includes both constitutional and

1 According to Weidenfeld, “Beiträge zur Klinik und Pathogenese des Pemphigus,”

Vienna, 1904, those cases of pemphigus in which the malady begins in the mouth are

the gravest.

2 Klotz, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1909, p. 242, reports such a case.

25

386

INFLAMMATIONS

local remedies. The systemic treatment, which is of essential impor

tance in the grave acute and in the chronic varieties, is, upon the whole,

to be based upon general principles, any possible etiologic factor being

corrected, modified, or removed, the general health built up, and the

digestive tract looked after. In fact, a careful study of the whole

economy should be made. The patient should have the benefit of good

hygienic conditions. There are, however, certain remedies which have

acquired deservedly more or less reputation of exerting a specific influ

ence. First in importance is arsenic (Hutchinson, Morris, and others),

given in safe but increasing doses up to the point of tolerance. The

drug has in some cases a controlling influence, and it is sometimes cura

tive; its use should be persisted in, as it is usually after long administra

tion that its beneficial effects are to be expected; it should also be con

tinued in small doses for some time after the disease has disappeared.1

Sodium cacodylate by hypodermic injection is sometimes valuable.

Strychnin and large doses of quinin are likewise useful in some instances.

These three remedies, arsenic, quinin, and strychnin, probably the most

valuable in this malady, can advantageously be prescribed conjointly.

Iron in full doses, cod-liver oil, and linseed meal (Sherwell) are also of

service in some cases. Opium, especially in the vegetating form (Hutch-

inson), pilocarpin, and atropin (Crocker), have exceptionally proved of

advantage. It is a good field for the trial of vaccines. Change of

scene and climate is of distinct value in some instances. The dietary

should be generous, but of a plain and substantial character.

Externally applications of a soothing nature are the most grateful.

It is a good rule to open and evacuate the blebs as soon as they form,

immediately applying one of the local remedies. The various lotions

employed in the acute type of eczema, especially those containing sedi

ments, are valuable, and should be applied freely by dabbing on or by

compresses; or, instead of lotions, the several dusting-powders named,

particularly those containing boric acid. In painful and extensive cases

linimentum calcis is grateful. Engman and C. J. White2 commend

the free and very liberal use of drying powder, the former using corn-

starch powder and the latter borated talc; the patient is actually to live

in the powder. Sometimes ointments, such as the zinc oxid ointment,

an ointment containing 1 dram (4.) of calamin to the ounce (32.), a mild

salicylic acid ointment, from 10 to 20 grains (0.65-1.3) to the ounce (32.),

and salicylated paste are comforting. In cases in which the disease is

more or less general, bran baths, starch baths, gelatin baths, and occa

sionally an alkaline bath, followed by the application of an ointment,

will prove acceptable. In the most severe types the continuous bath

1 Pollitzer, Festschrift des Deutschen Hospitals, 1911, p. 546, reports an apparent

cure of a case of chronic pemphigus with severe involvement of the mucous membranes

with large doses of arsenic; Sutton, Boston Med. and Surg. Jour., March 9, 1911,

reports a rapidly favorable result in a single case from a dose of salvarsan. In a case

at Philadelphia Hospital, with slight tendency to vegetating type, first under Dr.

Hartzell‘s care and subsequently mine, rapid temporary improvement was noted from

a dose of salvarsan, but later to another dose there was no response, the patient sub

sequently dying from the disease.

2 C. J. White, “The Dry Treatment of Certain Dermatoses,” Jour. Cutan. Dis.,

Dec, 1912, p. 705.

DERMATITIS VEGETANS

387

(Hebra) is to be employed. In cases in which itching is a more or less

prominent symptom carbolic acid may be added to the lotions or oint

ments employed; or the other applications employed to relieve itching,

as mentioned in the treatment of eczema, may be resorted to. In pem

phigus occurring in infants and young persons the same general plan

of treatment is to be followed.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |