| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

LICHEN PLANUS

213

LICHEN PLANUS

Synonyms.—Lichen ruber planus; Lichen psoriasis.

Definition.—An inflammatory disease characterized by pin-head

to small pea-sized flattened, glistening, crimson or violaceous papules,

with often a slight central depression, and often an irregular or angular

base; tending to coalescence and the formation of areas with a rough

ened or scaly surface.

Symptoms.—The disease, first clearly described by Wilson,1 is

in the larger number of cases somewhat limited, but it may be more

or less widely distributed over the entire surface. The favorite sites

in the former are about the flexor aspects of the wrists and forearms

and the lower part of the leg. The limited form of the disease usually

begins insidiously. The lesions at first are discrete, scattered, bright

or dark red in appearance, slightly elevated, with a flattened, shining,

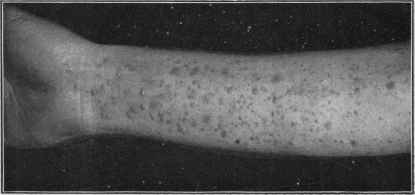

Fig. 40.—Lichen planus of moderate development, in a woman aged twenty-five,

and of several months’ duration. Practically limited to the arms and mainly on flexor

aspects.

or glistening top, in the central part of which there is usually a minute

depression. The base may be rounded; but more frequently it is irregu

larly quadrangular or angular, usually with perpendicular sides; excep

tionally minute stellate projections are noted at the base. In size they are

generally a trifle larger than a pin-head. In larger lesions, if present, there

may be, more especially after they have existed for some time, a wider

depression centrally, resulting in a slightly ringed formation; or occasion

ally new lesions spring up contiguous to the border while the central part

flattens down and partially or completely disappears. In occasional in

stances this ring-like tendency (annular lichen planus) in several or more

of the lesions or patches may be quite pronounced. Sometimes several

lesions will arrange themselves as a straight or irregular line. Excoria

tions and scratch-marks are apt to show a development of the efflores

cences. Lesions continue to arise, in the average case, close to others, and

1 E. Wilson reported a large number of cases in Jour. Cutan. Med., London, 1869,

vol. iii. No. 10.

214

1NFLAMMATIONS

several or more coalesce, and solid patches of various sizes result; the

surface of these is noted to be rough or slightly scaly. The scaliness

is generally insignificant or branny, usually quite adherent, but rarely

marked. The lesions and areas are now, as a rule, noted to be of a pur

plish color which is quite charac

teristic. Some may disappear,

leaving considerable pigmenta

tion, which is slow in fading.

In exceptional instances slight

atrophy may occur in places.1

Although some of the lesions and

areas may tend to disappear,

the eruption is, as a rule, persist

ent, new efflorescences appear

ing from time to time. The dis

ease may thus remain upon the

affected region, more particularly

the lower legs, and continue in

definitely, with but slight varia

tion.

While the plane or flat lesion

is the characteristic one of lichen

planus, in some cases there is an

admixture of a distinctly follicu-

lar and acuminate papule with or

without a slightly protruding

horny plug; exceptionally this

latter type may be predominant,

and in still rarer instances prac

tically all lesions may be of this

type.

In the leg region, and occa

sionally elsewhere—more especi

ally the forearms—the lesions

are sometimes much larger.

They are from a small to a

large pea in size, with rounded

or lenticular base, and flattened

or slightly conic in shape, dark red, brownish, or purplish in color,

with flattening of the summit or of the entire lesion; the surface

somewhat rough and branny or smooth (lichen obtusus; lichen planus

hypertrophicus). Occasionally the confluent plaques, especially about

or near the ankle, are markedly thickened, sometimes quite dark in

color, hard, rough, and wart-like—lichen planus verrucosus. Excep

tionally the lesions may be waxy in appearance. They may coalesce

1 See interesting paper on the variant forms, etc., by Crocker (“Lichen Planus: Its

Variations, Relations, and Limitations”), with discussion, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1900, p.

421; also Engman's report, “Annular Lichen Planus,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., May, 1901;

Lieberthal, “Lichen Planus Hypertrophicus.” Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, Jan. 11, 1902.

Fig. 41.—Lichen planus—hypertrophic

papules.

LICHEN PLANUS

215

and form large areas, as with the smaller papules; the central part

of the patches may persist, or it may disappear and show staining and,

exceptionally, atrophy. In rare instances this tendency to atrophy

in lichen planus (lichen planus atrophicus1) lesions is quite striking:

the individual papules tend to enlarge peripherally to the size of a pea

or dime, thinning centrally as they enlarge, and thus presenting a ring

appearance; eventually the whole lesion may become thinned down,

disappearing, and leaving behind an atrophic white spot. Doubtless a

few of the cases of so-called white spot disease (q. v.)2 may thus originate.

In occasional instances the white spot is somewhat sclerotic and mor-

phea-like (lichen planus morphœicus (Stowers), lichen planus keloidi-

formis (Pasolow)).

The more or less generalized form of lichen planus may begin as

such or develop from the limited form.3 The lesions usually appear more

or less rapidly, are at first rather pale red than deep red; some are waxy

and semitranslucent, and conic and rounded in shape, and may or may

not have the central depression. Many, and sometimes all, the lesions are,

however, similar to those described in the limited form—angular, flat,

dark red, and umbilicated. They are apt to appear, first, or most numer

ously, on the trunk, but the extremities are also invaded, and sometimes

markedly. Sooner or later the color becomes dark red or violaceous.

There is the same tendency toward close aggregation and coalescence

here and there, with the resulting solid patch, a trifle rough and scaly.

Exceptionally in some regions the lesions appear close together, forming

narrow, bead-like bands (so-called lichen ruber moniliformis). This

formation is likewise seen in the limited form, and may constitute the

major part of the eruption, as in cases reported by Kaposi, Dubreuilh,

and G. H. Fox.

The deep-red or violaceous color of the papules of lichen planus

as ordinarily met with is usually most marked on the lower parts of

the legs. Single isolated papules are usually free from any attempt

at scaliness; exceptionally, however, a minute, thin, filmy scale sur

mounts it. Minute whitish or grayish points and striæ, and sometimes

1 Dubreuilh and Petges, “Lichen plan atrophique,” Annales, 1907, p. 715, report a

case, and review reported cases (with references). Ormsby, Lichen planus sclerosus

et atrophicus (Hallopeau); a report of six cases (five new) with a review of the litera

ture, Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, Sept. 10, 1910, p. 901, with references and illustrations;

the writer found sites of predilection: upper portions of the trunk, about the breasts,

over the clavicles, extending over the shoulders and downward over the upper part of

the back, also the neck, axillæ, and forearms. The characteristic lesion is an irregular,

often polygonal, flat topped, white papule, with occasionally a yellowish tinge; on a

skin level or slightly elevated, with one to several or more black or dark horny, comedo-

like plugs, or minute pit-like depressions showing the sites of former plugs; isolated

and in plaques, they leave white delicate smooth scars. Radiotherapy is beneficial.

2 F. H. Montgomery and Ormsby, “White Spot Disease,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1907,

p. 12 (third case—lichen planus atrophicus).

3 Exceptionally such a case develops in such a way as to suggest a systemic malady.

D. W. Montgomery and Alderson report (Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc., 1909, vol. liii, p.

1457, with brief review and references) a case of lichen planus appearing acutely, the

eruption being profuse and more or less general, with brighter colored lesions, quite

fiery in appearance, with febrile and other constitutional disturbances—indicative of a

constitutional disorder—suggestively similar to the acute exanthemata. Engman and

Mook, Interstate Med. Jour., June, 1909, cite cases and circumstances favoring the

idea that this disease is a systemic one (review and references).

2l6

INFLAMMATIONS

minute red points, are not infrequently to be seen on the surface of the

lesions, more particularly those of larger size, and especially where co

alescence has taken place, the presence of which Wickham1 considers

pathognomonic of this disease. On the other hand, the shining or glazed

appearance which may be readily seen when the lesions are looked at

askant, is usually observable on all discrete lesions.

While the eruption may be quite extensive and be distributed in

smaller and larger plaques over the entire surface, it is never univer

sal. Even in extreme cases there are always some, and usually many,

free areas. It is, as a rule, more or less symmetric, although cases are

met with in which the areas of disease may be on one side, and a few in

stances are on record in which it had a zoster-like distribution. The

face is an uncommon site, even when the eruption is abundant. The

palms and soles are only occasionally involved.

Occasionally summit vesiculation is noticed in some of the lesions;

and exceptionally distinct vesicles and blebs, as in cases recorded by Unna,2

Kaposi,3 Lèredde,4 Mackenzie,5 Hallopeau and Le Sourd,6 Colcott Fox,7

Allen,8 Whitfield,9 Engman,10 and others; in rare instances it may be quite

a pronounced feature. It has been suggested that, in some of the cases

at least, the vesicular and bullous lesions might be due to the arsenic so

commonly administered in this disease, but in Whitfield‘s review of 17

collected cases, in 9 of the patients this drug had not been taken.

The mucous membrane of the mouth is quite frequently the seat of

lesions (E. Wilson, Hutchinson, Crocker, and others), and sometimes

it begins there primarily, as Thibiérge,11 Crocker,12 Petersen,13 and others

have shown; it sometimes precedes the skin eruption by some weeks, and,

in rare instances, continues practically limited to this region.14 In this

1 Wickham, Annales, 1895, p. 517.

2 Unna, Medical Bulletin, Phila., 1885, p. 145.

3 Kaposi, Archiv, 1892, pp. 340, 342, and 344.

4Lerèdde, Annales, 1895, p. 637.

5 Mackenzie, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1899, p. 26.

6 Hallopeau and Le Sourd, Jour. mal. cutan., Nov., 1899 (vesicles—in palms).

7 Colcott Fox, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1895, p. 22.

8 Allen, Trans. Amer. Derm. Assoc. for 1901; Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1902, p. 260.

9 Whitfield, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1902, p. 161 (with case and histologic illustrations).

10 Engman, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1904, p. 207 (with case and histologic illustrations and

bibliography); Miller, “A Case of Lichen Planus Bullosus,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1911, p.

332 (with pertinent bibliography).

11 Thibiérge, “Des lésions de la muquese linguale dans le lichen planus,” Annales,

1885, p. 65 (this contains a review of published cases).

12 Crocker, “On Affections of the Mucous Membranes in Lichen Ruber vel Planus,”

Monalshefte, 1882, vol. i, p. 161.

13 Petersen, St. Petersburg med. Wochenschr., 1899, p. 33 (brief case report). See

also Teuton‘s paper, “Casuistisches zum Lichen ruber planus der Haut und Schleim-

haut,” Berlin, klin. Wochenschr., 1886, p. 374 (with references).

14 Some recent contributions on lichen planus of the mucous membranes are: Mew-

born, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1905, p. 176 (case presentation). Among 10 unusual cases

reported by Beltmann (Archiv, vol. lxxv, p. 379) is one in which the only regions in

volved were the mouth and urethra; Vorner, Dermatolog. Zeitschr., 1906, vol. xiii, p. 107,

notes that umbilication may also be observed in these mucous membrane lesions;

Dubrenilk (“Histologie du lichen plan des muquenses,” Annales, 1906, p. 123) states

that the lesions of the mucous membranes are histologically essentially the same as those

of the skin); Lieberthal, “Lichen planus of the oral mucosa,” Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc,

Feb. 16, 1907 (2 cases, with illustrations); Favera, Monatshefte, 1909, vol. xlviii, p. 293

(with 2 histologic cuts and partial bibliography).

LICHEN PLANUS

217

region the disease consists of white or whitish dots or papules, plaques,

or streaks, as a rule but slightly raised. It bears a strong resemblance

to the appearances produced by cauterization with silver nitrate. As

a rule, these lesions give rise to no discomfort; occasionally there is a

feeling of slight soreness.

The glans penis has likewise been noted to be the seat of lesions, and

sometimes before their appearance elsewhere, as recorded by Bulkley1

and others.2 The eruption has also been observed on the inside and

outside of the vulva, as well as on the anal mucosa. On the glans penis

as well as on the vulva the lesions, which sometimes tend to the annular

development, are either white, when the part is habitually covered, or

of the usual color observed elsewhere when uncovered. It is thought

not improbable that in the more or less generalized cases of lichen planus,

especially the acute rapidly spreading variety, the mucous membranes of

the gastrointestinal tract may be also involved.

The disease in children usually presents the same symptoms as

when occurring in adults, but there is a type occurring in infants, de

scribed by Crocker3 and Colcott Fox,4 in which the eruption (quoting

Crocker) comes out acutely in groups, each papule of which is some

times acuminate at first, but the top seems to die down and a scale

comes off, leaving a smooth, shining, angular papule, of a brighter red

than usual, though it may get a purplish tint subsequently. Limbs,

trunk, or both may be the seat of the eruption. There is considerable

itching.

The course of lichen planus is in most cases slow, insidious, and

chronic. In some instances, it is true, as already remarked, the out

break may be extensive and somewhat rapid, but, as a rule, the erup

tion is slow in development, and in the majority of patients somewhat

limited in extent. In many of the limited cases, after reaching a cer

tain point, it may remain practically stationary for a long time, or

there is retrogression of some lesions along with the appearance of

new papules. Exceptionally, it tends after a time to disappear spon

taneously, but, as a rule, it is persistent. There are rarely any gen

eral symptoms except in cases of acute outbreaks or exacerbations,

and even then but slight and transitory. In more or less generalized

cases a marasmic tendency has occasionally been recorded.

The subjective symptoms, consisting of burning and itching, but

usually the latter, vary somewhat in different cases and often in the

same case. Occasionally the itching is not troublesome or so slight

as to give rise to no complaint; generally, however, it is an annoying

symptom, and sometimes so intense as to deprive the patient of restful

sleep.

Etiology.—The disease is not frequent. It is seen in both sexes,

and most commonly during active adult life, being rare in children.

1 Bulkley, Arch. Derm., 1881, p. 135.

2 Fordyce, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1912, p. 351, demonstrated a case with lesions on

the penis and mucous membrane of inner side of cheek—nowhere else.

3 Crocker, Diseases of the Skin, first ed., 1888, p. 215; second ed., 1893, p. 302.

4 Cotcott Fox, “Notes on Lichen Planus in Infants,’’ Brit. Jour. Derm., 1891, p.

201 (7 cases).

2l8

INFLAMMATIONS

Exceptionally the malady has been observed in two or three members

of the same family (Brocq, Lustgarten, Ormerod, Ledermann, Jadassohn,

Hallopeau, F. Veiel, and others).1 It is most frequently observed in

those of the neurotic class, after prolonged worry, overwork, anxiety,

nervous shock, or exhaustion; and is met with relatively oftener in private

than dispensary practice. In fact it would seem, in most cases at least,

that the disease is the result of disturbance of the nervous system. This

appears to have further support in the fact that it has occasionally been

noted to follow nerve distribution and also nerve injuries. It, however,

occurs in those apparently well nourished as well as in those showing

malnutrition.

Almost all authors of note recognize its frequency among the ner

vously depressed and exhausted. Duhring2 holds strongly to this view,

stating that, according to his experience, patients are generally found to

be suffering from debility arising from improper nourishment, overwork,

nervous depression, and similar conditions, and that nervous symp

toms are often prominent. I have myself long had under observation 2

cases (women) who have had recurrences when worn out with prolonged

winter social exactions. A few others hold the view of a possible systemic

infection.3

According to Crocker and Colcott Fox, the infantile cases seem, for

the most part, to occur in those whose vitality has been weakened by

constitutional taint, such as scrofula, syphilis, and the like.

Pathology.—Lichen planus is apparently an inflammatory proc

ess, but what the initial exciting pathologic factor is remains as yet

unknown. That it is a neuropathic affection seems probable, Col-

cott Fox suggesting that the first step may be a neuroparalytic hyper-

emia. The question 4 of its relationship to pityriasis rubra pilaris (lichen

ruber) is still an unclosed one, although the large preponderance of

opinion considers them two distinct affections. It seems certain, how

ever, that in some cases of extensive lichen planus occasionally papules

similar or closely similar to those characterizing pityriasis rubra pilaris

(lichen ruber) are observed.5

The pathologic anatomy has been studied by Robinson, Crocker,

Török, Unna, Polano, Fordyce, Sabouraud, and others. The disease

1 F. Veiel, “Lichen ruber planus als Familienerkrankung,” Archiv, vol. xciii, H. 3,

1908.

2 Duhring, Diseases of the Skin, third ed., 1882, p. 259; Spiethoff reports (Archiv,

Jan., 1911, Bd. cv, H. 1 and 2, p. 69) a case in which there was an associated pernicious

anemia.

3 Norman Walker (Introduction to Dermatology) thinks it possible that it may

later be found among the infective granulomata.

4 See Discussion, Compt. Rend., “Congréss Internat. de Derm, et de Syph.,” Paris,

1889.

5 Kaposi believes that lichen planus, sometimes called the lichen planus of Wilson,

is related to the malady described by Hebra as lichen ruber, and to the former he gave

the name lichen ruber planus, and to the latter, lichen ruber acuminatus. This view

obtained for some years, but was followed by a more or less general reversion, and

the acceptance of the opinion that these two so-called types or forms really represented

two distinct and separate cutaneous maladies, although a few eminent diagnosticians, as

Neumann and Hebra, Jr., as well as several others, have noted cases in which the two

coexist. Lichen ruber acuminatus, Kaposi further considers, as is now generally ad

mitted, as identical with pityriasis rubra pilaris.

LICHEN PLANUS

219

has its seat in the upper part of the corium, and usually around a sweat-

duct. The hair-follicles have no determining influence in the situa

tion of the papules. The changes are somewhat different, depending

upon the duration and character of the lesion. The rete and corneous

layer are noted to be thickened, and the papillæ enlarged, the vessels

of the latter showing dilatation. Fordyce1 noted the earliest changes

to consist in dilatation of the vessels and lymph spaces of the papillæ.

The papule results (Sabouraud)2 from a proliferation of the mononuclear

cells in the papillæ crowding out the interpapillary processes of the

epidermis, becoming edematous to a variable degree, even in some in

stances, to the degree of vesiculation. The central point of the depression

usually corresponds to the sweat-duct orifice, the depression resulting

from reabsorption and degeneration of the infiltration; the sweat-glands

are not affected.

The first characteristic change noted in the epidermis is thought to

be an acanthosis, followed by epithelial atrophy, and a hyperkeratosis,

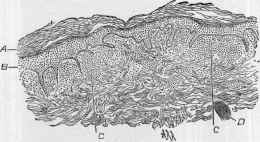

Fig. 42.—Lichen planus—section of two contiguous papules of not very long stand

ing (low magnification): A, Corneous layer, thickened slightly; B, rete and granular

layers, considerably thickened; C, C, round-cell collection in upper part of the corium

and papillæ, some of the latter thus crowded out, others enlarged by the increase in

length of the interpapillary rete; D, muscle bundle (courtesy of Dr. A. R. Robinson).

intercellular edema, and colloid degeneration of the prickle-cells. Histo-

logically, the mucous membrane lesions present the same features as those

of the skin.

Diagnosis.—The irregular and angular outline, the flattened top,

the slight central depression, the glistening or glazed appearance, the

dull red or purplish color, the tendency to patch-formation of a slightly

rough and scaly surface, with outlying typical papules, together with the

history and course and usually itchy character—are features which are

peculiar to this disease, and will generally prevent an errror in diagnosis.

The larger patches look somewhat like psoriasis, but the distribution is

different and they are less scaly, of different color, and about the edges

are to be found the characteristic papules. A patch of psoriasis is due to

peripheral extension, that of lichen planus usually to accretion of new

papules.

1 Fordyce, “The Lichen Group of Skin Diseases; A Histologic Study,” Jour. Cutan.

Dis., 1910, p. 57 (with excellent histologic illustrations).

2 Sabouraud, Annales, 1910, p. 491 (pathologic anatomy; excellent illustrations).

220

INFLAMMATIONS

While the patches of the disease may resemble squamous eczema,

the characters of the papules, always to be found, are essentially dif

ferent; and in an extensive papular or scaly eczema there is often the

presence of a few intermingled vesicles or a history of such or of oozing;

lichen planus is in almost all cases a dry disease throughout, and the

lesions are papular and not vesicular, moreover, the papules of eczema

are rounded or acuminate. It is only in exceptional instances that some

of the lesions of lichen planus may show vesicular and bullous develop-

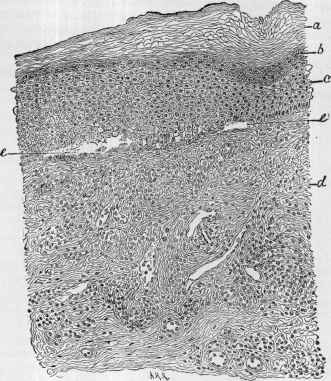

Fig. 43.—Lichen planus—section from a chronic patch (moderately high magnifica

tion) : a, b, c, Show respectively the corneous layer, granular, and rete—all consider

ably thickened; e, e, microscopic cavities, with serous exudate; d, corium, infiltrated

with exuded round cells, and with marked increase in the size of the connective-tissue

corpuscles (courtesy of Dr. A. R. Robinson).

ment—all of the other papules preserving their usual characteristics

throughout.

I have known it to be mistaken for the miliary papular syphiloderm,

but in this latter the lesions are usually rounded or conic, and, while

tending to aggregate, do not form solid areas, are of a somewhat different

color, and almost invariable show some scattered miliary pustules, and

often a few larger pustules; moreover, it being an eruption of the active

stage of syphilis, there are corroborative signs of that disease to be

found.

LICHEN PLANUS

221

From pityriasis rubra pilaris the following differences are usually

given: the lesions of pityriasis rubra pilaris are round or conic, not shining

or glistening, not irregular in outline; are rarely umbilicated; show

a scaly film on the summit; are red, and never violaceous, in color;

and while the eruption is limited at first, it tends to general involve

ment. According to Hebra's own description, however, there would

seem at times a clinical resemblance in some of the papules of the two

affections. Those of pityriasis rubra pilaris are, however, seated about

the hair-follicles.

Prognosis.—Its natural course is persistent and often progressive,

and shows little tendency to spontaneous recovery. With treatment

it can be cured, sometimes in a few months, but oftener a much longer

time is required. There is in some cases a disposition to one or more

recurrences. The pigmentation finally disappears, but sometimes

months elapse before it is entirely gone; occasionally on the legs the

discoloration is permanent.

Treatment.—The patient is to have the benefit of good plain

food, hygienic living, and, when possible, outdoor life and freedom

from mental worry or care. The various tonics and cod-liver oil may

be prescribed when indicated. The main remedies in this disease,

however, are arsenic, mercury, quinin, and strychnin. Arsenic in many

cases has a direct specific influence, given in increasing doses to the

point of tolerance, and continued for some time; mercury is also valuable

and seems to have a direct action in some instances. These two drugs,

and especially the former, are, if no contraindications exist, to be, as a

rule, always prescribed, and, along with other indicated remedies, usually

lead to recovery. The former is given in the beginning dosage, three

times daily, of 2½ or 3 minims (0.165 or 0.2) of Fowler's solution or sodium

arsenate solution, or the equivalent of arsenious acid, and gradually in

creased to 5, 6 (0.33, 0.4), or more; larger doses than 10 minims (0.65)

are rarely required, and if no benefit is obtained with this amount, it is not

likely to ensue from a greater quantity. Mercury can be given in the

form of the corrosive chlorid (Norman Walker), or the biniodid in the

dose of 1/32 to 1/12 grain (0.002 to 0.0055), or as the protiodid in dosage of 1/8

to ½ grain (0.008 to 0.033). Quinin is also valuable, and should be given

in fairly full doses—9 to 15 grains (o.6 to 1.) daily. Hartzell has had

favorable action in some instances from sodium salicylate.1 Strych

nin is an excellent tonic in these cases. Constitutional treatment2

should, as a rule, be continued, in somewhat lessened dosage, one or two

months after the eruption has disappeared.

External treatment is of great importance, both for influencing

the eruption and for allaying the itching usually present, and in the

limited form of the disease often alone suffices to bring about a cure.

1 Hartzell, “The Salicylates in the Treatment of Lichen Planus,” Jour. Amer. Med.

Assoc, 1907, vol. xlix, p. 225 (with a report of some unusual forms).

2Hutchins, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1912, p. 615, describes an interesting case of dif

fused lichen planus (in a male, six years of age), followed by vesicobullous infected

lesions, some of the vesicles and bullæ where lichen planus lesions had not been; cured

by an autogenous vaccine made from culture of the staphylococcus obtained from a

vesicle.

222

INFLAMMATIONS

In cases of any considerable extent alkaline baths every other day, or

in irritable cases, bran, gelatin, or starch baths daily, are of service, to

be followed on the patches with ointment applications or with lotions.

The most efficient application in the general run of cases is liquor car-

bonis detergens; this is to be applied at first diluted with 10 to 15 parts

water, but if no irritation is produced, it may gradually be strengthened,

and in some cases can be used pure. It is to be dabbed on thoroughly

twice daily, and oftener if the itching demands it. It the skin becomes

unpleasantly dry or harsh, its application can occasionally be followed

with cold cream; or it may be prescribed in ointment form, 1 or 2 drams

(4. to 8.) to an ounce (32.) of simple cerate or a mixture of simple cerate

and cold cream. The vegetable tars, expecially the oil of cade and oil of

birch (oleum rusci), are also excellent in chronic cases, but are stronger

than liquor carbonis detergens, and have a more marked and persistent

odor; they are best applied in ointment form, 1 to 2 drams (4. to 8.) to the

ounce (32.). In acute inflammatory and irritable cases the calamin-zinc-

oxid lotion and the plain or carbolized boric acid lotion act satisfactorily,

stronger applications—liquor carbonis detergens—being resorted to

later. This calamin-and-zinc-oxid lotion and the other mild lotions used

in eczema can also be advised for the disease occurring in infants and

children. For thick, hardened, or verrucous areas, a 10 to 20 per cent,

salicylic acid rubber plaster or plaster-mull can be used until the thick

ness is reduced; or paintings with varying strength of caustic potash solu

tions, beginning with the liquor potassæ, can be used cautiously, washing

off immediately afterward, and supplementing with a mild ointment, such

as zinc-oxid or diachylon ointment. In obstinate patches of this charac

ter stimulation or slight superficial cauterizing action with carbon-dioxid

snow (q. v.) can be cautiously tried.

When the lesions are close together and patchy, as on the fore

arms, the galvanic current, of 4 to 10 milliampères in strength, applied

three or four times weekly, has had in some of my cases a material

influence; the application should be rapidly labile, except over thick

ened areas, where the electrodes can be held stationary for one or two

minutes. In these cases, too, the static current applied with the roller

electrode and the high-frequency current applied with the flat vacuum

electrode are also sometimes of service.

A Chronic Itching Lichenoid Eruption of the Axillary and Pubic

Regions.—Brocq, Fox, Fordyce, Haase,1 and others have reported

cases, few in number, characterized by a more or less limited and

localized patch formation usually in the axillary and pubic regions,

made up of closely set, more or less coalescent, somewhat firm or hard

pin-head to pea-sized papules, seemingly seated on, and an intimate

1 G. H. Fox, “Two Cases of a Rare Papular Disease Affecting the Axillary Regions,”

with histopathologic report by Fordyce, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1902, p. 1 (with histologic

cuts); Fordyce, “A Chronic Itching, Papular Eruption of the Axillae and Pubes; Its

Relation to Neurodermatitis,” Trans. Amer. Derm. Assoc., for 1908, p. 118 (with case

and histologic cuts); Haase, “A Chronic, Itching Papular Eruption of the Axillae,

Pubes, and Breast,” Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, Jan. 21, 1911 (with case and histologic

cuts).

LICHEN PLANUS

223

part of, a locally infiltrated thickened skin. Some of the lesions show

a slight central depression, some are flattened, some rounded, and

most of them showing a central grayish plug. The lines of the skin

of the involved area are accentuated, and when the skin is put on

the stretch markedly so. The lesions and patch are of normal skin

color or dirty gray, sometimes with a dull violet or pinkish tinge.

The process is, as a rule, insidious in its appearance and is an ex

tremely sluggish one, very slow in progress and after a time usually

remaining stationary. The itching is often a prominent symptom, occa

sionally at times almost intolerable, and some of the papules are generally

noted to be excoriated. The itching is often the first symptom observed,

leading to rubbing and scratching, and being sooner or later followed by

the papulation and thickening. The hairy parts of the axillary and pubic

regions are favorite sites—less frequently about the nipples also. The

hairs of the affected part, after the appearance of the lesions, usually

become brittle and lusterless, and to an extent, or even completely,

break off or fall out. The malady is persistent and rebellious to treatment.

The clinical picture is suggestive of the combined symptomatology of a

pityriasis rubra pilaris, lichen planus, and a papular selerous eczema. It

represents a condition or class of cases called “lichenification” by the

French; and Fordyce and Haase believe it should be placed under Brocq's

group of “chronic circumscribed neurodermatitis (névrodermite chronique

circonscrite).“ Most observers have doubtless placed these rather rare

cases as variant examples of lichen planus or eczema. Histologically

there were found acanthosis and some parakeratosis, with hypertrophied

papillæ, edematous at their tips; lymphocytic infiltration about the ves

sels and pilosebaceous apparatus, with, in some instances, involvement of

the sweat-gland apparatus also.

Lichen nitidus is a rare eruption, first described by Pinkus

(1901), and since by this same writer (9 cases in all), Lewandowsky

(2 cases), Arndt (12 cases),1 Kyrle and McDonagh (1 case),2 and Sutton.3

The lesions are small, usually flat, sharply margined papules, roughly

circular or polygonal in shape, scarcely raised above the level of the

skin, of skin color, pale red, or yellowish brown. They are almost

uniformly of the same size, and often a minute aperture can be detected

in the center of the papule. The lesions are usually disseminated,

never coalesce or show any disposition to form groups, although some

times they may tend to pack together closely. They are persistent

and without change; after years they may spontaneously disappear,

leaving no trace. The favorite regions are: the genital organs (its most

typical site), abdomen, especially about the umbilicus, the flexures of

1 Arndt, Dermatolog. Zeitschr., 1909, vol. xvi, H. 9 and 10 (clinical, histologic, with

review); good abstract in Brit. Jour. Derm., Jan., 1910.

2 Kyrle and McDonagh, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1909, p. 339 (case, a girl aged eighteen;

eruption more or less generalized; histologic plate; and résumé of Pinkus’ cases).

3 Sutton, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1910, p. 597, case, male, aged thirty-five; eruption on

anterior fold of both axillae, in groin, around the umbilicus, upper anterior surface of

each forearm, flexor surfaces of the wrists, and dorsal aspect of both thumbs; ex

perimental inoculations (two guinea-pigs) negative; histologic and case illustrations

with review and references.

224 INFLAMMATIONS

the elbows, and the palms. There are no subjective symptoms, and this

and the fact that the eruption is insignificant, usually on covered parts,

and often scarcely noticeable except upon close examination, probably

explain why so far all the cases have only come accidentally under obser

vation; with one exception they were all male subjects. Nothing is

known as to its etiology and pathogenesis, although Kyrle and McDonagh

believe it is probably brought about by a tuberculous toxin. Histolog-

ically, a lesion has a structure resembling tubercle.

The papules have some resemblance to those of lichen planus, and

also a variable suggestiveness of small multiple flat warts, the flat form

of lichen scrofulosum, and lichenoid syphiloderm. The malady does

not seem to be materially influenced by treatment.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |