| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

DERMATITIS HERPETIFORMIS1

Synonyms.—Hydroa bulleux (Bazin); Hydroa herpetiforme (Tilbury Fox);

Duhring‘s disease; Dermatitis multiformis (Piffard); Herpes gestationis; Pemphigus

pruriginosus; Herpes circinatus bullosus (Wilson); Pemphigus circinatus (Rayer);

Herpes phlyctænodes (Gilbert); Pemphigus prurigineux (Chausit, Hardy); Pemphigus

composé (Devergie); Dermatite polymorphe, Dermatite herpetiforme (Brocq).

Definition.—Dermatitis herpetiformis is a rare inflammatory

disease, with or without slight or grave systemic disturbance, char

acterized by an eruption of an erythematous, papular, vesicular, pus

tular, bullous, or mixed type, with a decided tendency toward group

ing, accompanied usually by intense itching and burning sensations,

with more or less consequent pigmentation, and pursuing a persistent,

chronic course with exacerbations.

Symptoms.—The onset and the exacerbations may or may not

be preceded for a few days by symptoms of general disturbance, such

as malaise, loss of appetite, constipation, chilliness, flushings and heat

1 Most of Professor Duhring‘s papers, establishing a fixed place in classification for

this disease, have been republished in Selected Monographs on Dermatology, issued by

New Sydenham Society, London, 1893, pp. 179-297. A most excellent French exposi

tion of the subject, with numerous literature references and brief recital of most pub

lished cases, is that by Brocq, entitled “De la dermatite herpétiforme de Duhring,” An

nales, 1888, pp. 1, 65, 133, 209, 305, 434, and 493. A graphic and succinct descrip

tion of the disease read by Jamieson before the London Dermatological Society, and the

discussion thereon, present the English views of the subject, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1898,

pp. 73 and 118. As one of the earliest contributions must be mentioned the suggestive

and elaborate paper by Tilbury Fox, “Clinical Study of Hydroa,” Arch. Derm., 1880,

p. 16 (a posthumous paper, edited, with notes, by Colcott Fox).

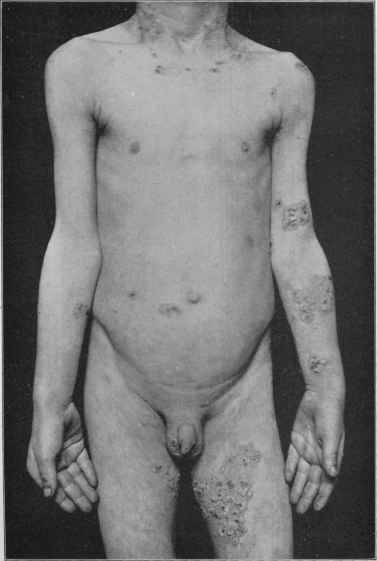

Plate XII.

Dermatitis herpetiformis of the vesicular and papulovesicular variety in a male adult aged

forty, of about five years’ duration ; shows the herpetic grouping of the lesions.

Plate XIII.

Dermatitis herpetiformis ; erythematovesicular and pustular varieties in combination

Woman, middle age. Eruption more or less generalized (courtesy of Dr. Louis A.

Duhring).

DERMATITIS HERPETIFORMIS

365

sensations, rise of temperature, and often the subjective symptom of

itching. During the first several days of the cutaneous outbreak such

symptoms may in greater or less degree continue; and in the more severe

and extensive types of the disease, especially in the pustular and bullous

varieties, the constitutional symptoms may be of a graver character and

more or less persistent. Cases in which the general symptoms give rise

to anxiety are, however, it must be said, infrequent, and in most instances

are entirely wanting or extremely slight.

The eruption may be erythematous, papular, vesicular, bullous, pus

tular, or mixed; it is never ulcerative. Very rarely purpuric lesions are

intermingled or follow in the pigment stains from the vesicles and blebs,

and the latter lesions are exceptionally slightly hemorrhagic (Brocq,

Tenneson, Hallopeau, Leredde, Perrin). The vesicular variety is the

most common. In some cases the same type with which the eruption

begins may persist or be preponderant throughout the course of the

malady; there is in many, however, a distinct tendency to change from

one to another, in some cases completely, in others, partially. The

onset of the outbreak may be sudden, or it may be preceded for several

days or weeks by slight cutaneous irritation, such as itching, one or

several insignificant erythematous patches, groups of vesicles, or urti-

carial lesions; or the first lesions are all of one variety. When fully

developed, the eruption may cover almost the entire surface; or it

may be more or less limited in extent, involving a greater part or the

entire trunk; or the trunk may be but slightly invaded, and the limbs,

especially the legs, bear the brunt. C. Boeck1 has observed a special

predilection for the regions of the elbow, shoulder, lower sacral, and

poplitea, and thinks this so constant as to be almost diagnostic It

is, however, in every way, both as regards violence and extent, variable—

slight or severe, limited or extensive. Itching is usually a constant

and a most troublesome feature; pigmentation sooner or later is noted in

most cases. After several days or weeks of violent activity the disease

tends to become, slowly or rapidly, less active, and a period of compara

tive comfort and freedom of uncertain duration is passed. These

remissions or intermissions are irregular and capricious; in some instances

scarcely one violent outbreak is in full development, when another, equally

active and extensive, follows, and this may continue in rapid succession

for several months or longer before a period of comparative or complete

quiescence intervenes.

The vesicles, pustules, and blebs, especially the vesicles and blebs,

are somewhat peculiar as to shape; they are, or many of them at least,

usually of a strikingly irregular outline, oblong, stellate, quadrate,

semilunar, or rarely ring-shaped, distended, or flaccid, and when drying

are apt to have a puckered appearance. They are herpetic, in that they

show little disposition to spontaneous rupture; occur mostly in groups

of two, three, or more, and not infrequently are seated upon erythematous

or inflammatory skin. Occasionally some of the lesions, especially in

the graver cases, contain a slight admixture of blood. They may dis

appear by absorption, or, if ruptured or broken, leave abrasions which

1 Boeck, Monatshefte, 1907, vol. xlv, p. 277.

366

INFLAMMA TIONS

may secrete for a short time and dry up; or they may dry to crusts which

fall off, the sites being marked by erythematous spots, which in turn

fade or leave behind slight pigmentation. In size the vesicles are rarely

smaller than a pin-head, and are usually the size of small peas. The

blebs may be almost any dimension from a pea to a hen's egg, and may

arise as a single lesion from sound or erythematous or erythematopapular

skin, or may have their origin in the confluence of several closely con

tiguous vesicles or small blebs. Scattered pustules may be large, but

more commonly are all small in size, resembling in this respect vesicular

lesions; they often begin as pustules, or may have their origin in vesicles.

The mucous membrane of the mouth, throat, nose, and eyes is in some

instances—more especially the bullous cases—involved, and in excep

tional cases the mucous membrane of the trachea and the larger bronchial

tubes also.

The erythematous type lesions are similar to those of a general

ized erythema multiforme, and it could be very aptly designated a

chronic form of that affection, except that at times it is noted to change

completely into one of the other varieties; urticarial lesions are now and

then interspersed. It is sometimes a beginning type; quite often it

appears as a break of short or long duration between active vesicular

or bullous outbreaks; and not infrequently it is the type permanently

assumed after the violent character of the disease has disappeared.

In children (in whom the disease has been especially studied by

Gottheil, Meynet and Péhut, Halle, Bowen, Knowles, Gardiner, and

others)1 the element of multiformity is often wholly lacking, the erup

tion being of a vesicular and bullous character without admixture of

other types. The eruption in many of these cases is frequently pre

dominant on certain regions, as about the nose, mouth, neck, axillary

folds, genitalia, wrists, and hands; and occasionally it is limited to these

parts. Subjective symptoms are often absent and only rarely trouble

some; and pigmentation is seldom a feature.

Etiology.—The disease is rare, but not so rare as formerly thought.

It is met with in both sexes and almost all ages. It is most frequent

during the period of active adult life, although it is exceptionally seen

in the very young (one aged three—Pringle; one aged four—Bowen).

In some cases there is found nothing of import in the previous or present

condition of the patient's health to explain the cutaneous phenomena;

in fact, in some the general health seems undisturbed. Still, enough is

1 Gottheil, Arch. Pediat., June, 1901, reports 2 cases in children—in one aged nine,

beginning when aged four; Meynet and Péhut, Annales, 1903, p. 893, in reporting a case

in a child, give a résumé of previously reported cases in children, with references; Halle,

Arch, de méd. d. enfant, 1904, vol. vii, p. 385, reviews the character, etc, of the disease

in children, of which he has seen 5 cases; Bowen, “Dermatitis Herpetiformis in Chil

dren,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1905, p. 381, records 15 cases, with review of some other

cases, and allied conditions, with references; Knowles, “Dermatitis Herpetiformis in

Childhood,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1907, p. 246 (report of a case, with 2 illustrations, and

a complete summary and analytic review of 57 collated cases, with bibliography);

Gardiner, “Dermatitis Herpetiformis in Children,” Brit. Jour. Derm., Aug., 1909, p.

237 (report of 4 cases, with 7 illustrations); Sutton, “Dermatitis Herpetiformis in

Early Childhood,” Amer. Jour. Med. Sci., Nov., 1910, vol. cxl, p. 727 (case report—

child three and one-half years, beginning when nine months old; numerous tiny

scars; review and references of early cases).

Plate XIV.

Dermatitis herpetiformis ; vesicobullous variety. Irregular bullous lesions, resem

bling those of erythema multiforme bullosum. Eruption general. Patient, a woman

(courtesy of Dr. Louis A. Duhring).

DERMATITIS HERPETIFORMIS

367

known to indicate that the disease is essentially neurotic, for in other

instances—in a large number, in fact—it manifests itself after severe

mental strain, emotion, and nervous shock, as frequently recorded

(Tilbury Fox, Duhring, Elliot, Devergie, Crocker, Vidal, Tenneson,

Brocq, and others). Its connection with the nervous system is also

shown by the cases in which pregnancy is the factor, the malady often

disappearing in the interim, of which many examples are on record

(Milton, Bulkley, Liveing, W. G. Smith, Duhring, White, Perrin, and

others). The possible reflex origin in some instances is suggested in

the case of a child reported (Roussel) in which phimosis was apparently

the factor, a cure resulting after circumcision.1 Nephritic disease has

been associated or recorded as an etiologic factor, as shown by glyco-

suria (Winfield) and albummuria (Wickham, Abraham). According to

Besnier, there is always scantiness of urine, with diminution of urea and

uric acid. Engman2 found indicanuria an almost constant feature.

Physical or nervous breakdown, exposure to cold, and septicemia have

been apparently etiologic in some of my cases. Cases apparently septic

in origin have also been reported by others (Sherwell, Kerr, and others).

That some septic or otherwise toxic agent is sometimes responsible for

dermatitis herpetiformis (or at least a similar or allied condition, showing

often a combination of the symptomatology of erythema multiforme,

herpes, and pemphigus, and resembling dermatitis herpetiformis) seems

shown by the occasional examples following vaccination, as observed by

Dyer, Pusey, Bowen, myself, and others.3 Autointoxication, usually

gastrointestinal in origin, may be responsible for this as well as for other

allied disorders.4 The condition of the thyroid gland should be noted—

as its hypertrophy or atrophy may be the source of the toxic agent.

Sequeira5 has recorded the case of bullous eruption in a child of three,

suggestive of a beginning dermatitis herpetiformis; developing acute

symptoms of appendicitis (apparently a chronic case of some duration);

operation was performed, and with no return of the eruption since

operation. In some instances general debility and debilitating influences

may rightly be considered as responsible, in part at least, for a continu

ance of the disease. On the other hand, striking amelioration has been

noted6 by a physician in his own case during attacks of malarial fever and

other intercurrent disorders.

1 Kirby-Smith, New York Med. Record, Aug. 17, 1912 (1 case—with illustration;

promising result following circumcision).

2 Engman, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1906, p. 216, and 1907, p. 178, reports upon the con

stant presence of indican in the urine, and these amounts seemed to have relationship

with the eosinophilia; Loth and Grindon have also noted the presence of indican.

3 Dyer, New Orleans Med. and Surg. Jour., 1896-97, vol. xxiv, p. 211; Pusey,

Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1897, p. 158—the early history of this case was reported by Becker,

Tri-State Med. Jour., May, 1893; Bowen, “Six Cases of Bullous Eruption Following

Vaccination,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1901, p. 401 (in children between the ages of five and

ten, and appearing within from one to four weeks after vaccination, and lasting for

months and years); Stelwagon, “Vaccinal Eruptions,” Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc, Nov.

22, 1902; Bowen, Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1904, p. 265, refers to several other cases.

4 See interesting paper by Johnston, “The Evidence of the Existence of an Auto-

toxic Factor in the Production of Bullous Diseases,” Brit. Med. Jour., Oct. 6, 1906.

5 Sequeira, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1911, p. 295.

6 “Dermatitis Herpetiformis: A Personal Experience of the Disease,” Brit. Jour.

Derm., 1897, p. 97, and 1899, p. 282.

368 INFLAMMA TIONS

Pathology.1—Recent studies (Elliot, Leredde and Perrin, Unna,

Gilchrist) indicate that the process, inflammatory in character, has

its beginning in the upper corium—in the papillary layer, or in the deep

epidermic layers; and the resulting vesicle, forming beneath the epi

dermis, gradually or quickly enlarges and works upward, the epidermis

being secondarily involved. In the corium are noted variable edema,

dilatation of the vessels, and cell-masses of usually lymphocytes, occa

sionally of plasma-cells. Eosinophiles are found both in the corium and

epiderm, and are present usually in large numbers in the vesicles and

blebs, and also in the blood (Leredde, Brown). In the dilated vessels

are to be seen, in addition to the red blood-corpuscles, polynuclear leuko-

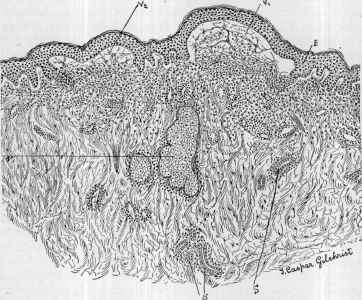

Fig. 88.—Dermatitis herpetiformis, vesicular variety (X about 35): V1 and V2,,

show small vesicles; E, epidermis unchanged, lifted up by the exudation; S, S, sweat-

gland and duct; G, sebaceous gland. The contents of vesicles consist of fibrin, coagu

lated albumin, polynuclear leukocytes, and, at the bottom, eosinophiles. Glandular

structures not involved. Upper half of corium shows acute inflammatory process,

with much fibrin (courtesy of Dr. T. C. Gilchrist).

cytes; in the larger vessels, eosinophiles in scanty number. The lesions

contain a fibrinous network, in the meshes of which are found polynu-

clear leukocytes in large numbers, some mononuclear and epithelial

cells, eosinophile cells, as already stated, and coagulated albumin. The

pustules are probably due to an added superficial infection from without.

1 Pathologic anatomy: Elliot, New York Med. Jour., 1887, vol. i, p. 449; Leredde et

Perrin, Annales, 1895, pp. 281 and 452; Gilchrist, Johns Hopkins Hosp. Reports, 1896,

vol. i, p. 365.

Regarding eosinophilia: Leredde et Perrin. Annales, pp. 281, 369, and 452;

Darier, ibid., 1896, p. 842; Leredde, ibid., p. 846, 1899, p. 355, and (also anatomy),

Gazette des Hôpitaux, March 26, 1898; Funk, Monatshefte, 1893, vol. xvii, p. 266;

Brown, Jour. Amer. Med. Assoc., Feb. 17, 1900; Bushnell and Williams, Brit. Jour.

Derm., 1906, p. 177 (diminished phagocytic power of the eosinophile cells).

Plate XV.

Dermatitis herpetiformis (?) sometimes met with in children, and also observed devel

oping after vaccination ; neck, axillary, genitocrural, popliteal, and elbow-flexure regions

seem favored ; vesicobullous and herpes iris type ; patient aged eleven ; two years’ dura

tion, with periods of comparative quiescence.

DERMATITIS HERPETIFORMIS

369

Leredde strongly believes that the excretion of eosinophile cells by the

skin to be an essential part of the cutaneous phenomena, and together

with the eosinophile cells in the blood are characteristic of this disease—

a view shared, in part at least, by others (Hallopeau, Lafitte, Danlos).

It is now known, however, that eosinophile cells are found in lesions of

other bullous diseases.

Diagnosis.—At various periods in its course a case of dermatitis

herpetiformis may resemble slightly or even strikingly erythema multi-

forme and pemphigus; and not infrequently, indeed, the clinical picture

may be for a time closely similar or even the same as one of these dis

eases, and without knowledge of its former history and course a mistake

could be readily made. Several factors need to be kept in mind in the

diagnosis as being more or less distinguishing: Chronicity, with or with

out remissions or short or long intermissions; multiformity, tendency

toward grouping, disposition to change of type, itchiness, with sooner or

later slight or marked pigmentation.

It is distinguished from erythema multiforme by the fact that this

latter is an acute disease running a course of ten days to several weeks,

and is unaccompanied by intense itching; moreover, its distribution is

rarely as irregular or general as that of dermatitis herpetiformis. The

vesicles and bullæ—herpes iris, erythema bullosum—which are occa

sionally seen in erythema multiforme have their origin in preexisting

erythematous lesions; while this also happens in dermatitis herpetiformis,

some of the vesicles and bullæ will be found to arise from apparently

healthy skin. In doubtful cases an observation of several days or, at

the most, a few weeks, would lead to a correct conclusion.

Pemphigus differs from the bullous type of dermatitis herpetifor-

mis in that the lesions of the former are usually larger and show no

special tendency to occur in groups or to assume irregular, angular, or

multiform shapes; the pemphigus blebs, moreover, appear, as a rule,

from sound skin, and the disease lacks the small vesicles and vesicular

groups and occasional small pustules and pustular groups usually found

intermingled in the bullous eruption of dermatitis herpetiformis. In

pemphigus itching is wanting or slight, whereas in dermatitis herpeti-

formis it is one of the most troublesome symptoms. The reported cases

of “pemphigus pruriginosus” are, doubtless, in many instances at least,

examples of dermatitis herpetiformis. Pemphigus with itching as a

symptom may be distinguished by the differential points already given,

especially when considered in connection with the known capriciousness

of type in dermatitis herpetiformis. The constitutional symptoms of

pemphigus are often quite marked—much more so, as a rule, than ob

served in dermatitis herpetiformis.

The characters of dermatitis herpetiformis are so different from

urticaria and eczema that a mistake is scarcely possible. In urticaria

the lesions are all wheals, there is no tendency to special grouping,

and it is usually acute and evanescent; bullous lesions in urticaria are

uncommon, and when present, spring from wheals and are associated

with other characteristic wheals. In eczema the papules and vesicles

are much smaller, and the eruption is rarely generally distributed.

24

370

INFLAMMA TIONS

Prognosis.—As to relief, much, as a rule, may be promised, but

as to cure or permanent freedom from outbreaks the prognosis cannot

be too cautiously guarded. It is not to be forgotten that dermatitis

herpetiformis is a particularly persistent and chronic disease, capricious

in its behavior and course, and rebellious to treatment. Permanent

recovery is to be considered rather exceptional; there is, however, a

tendency in most cases to become less active. Those showing a pre

vailing tendency to the erythematous form, and the vesicular expres

sion of the disease occurring in connection with pregnancy or the par

turient state (herpes gestationis) are the more favorable varieties. The

disease in children seems much less rebellious, and recovery is not so

uncommon as in adults. The pustular and bullous types are sometimes

of a serious character. A fatal ending is possible in the grave cases,

especially in those associated with septicemia. It must be conceded,

however, that dermatitis herpetiformis usually persists for years without

compromising life, and that in many of the patients the general health,

considering the violence of the eruptive phenomena, remains compara

tively undisturbed.

Treatment.—Although the etiology of dermatitis herpetiformis

is obscure, it is, in most cases at least, to be looked upon as of neurotic

nature. The most successful treatment, therefore, is one that keeps

in view the avoidance or correction of any factor detrimental or disturb

ing to the nervous equilibrium, and which also aims to bring about a

healthy and more vigorous nervous tone. The mode of living, the diet,

the state of the digestion, and the condition of the various internal

organs, more especially the liver and kidneys, should be investigated.

The diet should be generous, but plain and nutritious; coffee and tea,

except in very moderate quantity, should be avoided, likewise all indi

gestible foods. Alcoholic stimulants are usually damaging. Occa

sionally a purely milk diet, or with meat once daily, has a favorable

influence. In fact, the gastrointestinal tract should receive particular

attention, as the toxic material which may be responsible for the malady,

may have its origin here. A saline purge often has a favorable influence

in mitigating the severity of an attack; the bowels should always be

kept free. Upon the whole, constitutional treatment is based upon

general principles. Irrespective, however, of what may be indicated

by suspected etiologic conditions, three remedies need special mention—

arsenic, quinin, and strychnin in moderately full or large doses. Arsenic,

according to my own observation and those of others (Jamieson, Roberts,

Mackenzie),1 stands first in value; in small doses, it is often valuable as a

tonic, but in some instances, especially of the vesicular and bullous types,

pushed to the point of tolerance, it will be found of distinct service;

after it fails to do further good, it can be stopped, and then later resumed.

In other cases it seems to do harm. In persons of depressed general

nutrition cod-liver oil is a remedy of value. Alkalies and diuretics are

sometimes of service. Should there be a suspicion of hypothyroidism

the proper remedy (thyroid gland preparations) should be tried—

1 Morris and Whitfield, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1912, p. 148 (case demonstration and

discussion), give each a remarkable instance of control by arsenic.

PEMPHIGUS

371

favorable influence from its use in such instances have been recorded

(Sutton and Kanoky). Phenacetin (Morris, Pringle) or acetanilid will

occasionally favorably influence the itching. In severe cases narcotics

are necessary to procure sleep, but are to be avoided if possible. General

galvanization and static insulation are measures which may be of service.

In persistent cases in children the possibility of circumcision having a

favorable effect should be considered.

Regarding the external treatment, it will be found that, as a rule,

lotions of an antipruritic character will give the most relief. Blebs, if

present, should be opened and evacuated. In some cases weak alka

line and bran and gelatin baths are comforting. Liquor carbonis deter-

gens, 1 or 2 teaspoonfuls to a small teacupful of water, will often be

serviceable for controlling the pruritus; if well borne, and if the weaker

strengths afford no relief, this preparation may be used in stronger

proportion, often up to the pure solution. Ichthyol, in an aqueous

lotion, from 2 to 10 per cent, in strength, is also of value. Resorcin,

from a 1 to a 5 per cent, solution; carbolic acid, from 1 to 3 drams (4.-12.)

to the pint (500.) of water, with boric acid to saturation; liquor picis

alkalinus, from 1 to 3 drams (4.-12.) to the pint (500.) of water, applied

cautiously—are all of value in some cases and at different times in the

same case. These may be often advantageously supplemented by

bland dusting-powders or by the mild ointments, such as that of zinc

oxid, cold cream, and the petroleum ointments, plain or carbolized or

with from 1 to 10 grains (0.065-0.65) of menthol to the ounce (32.).

At times the washes are not well borne; then the ointments already

named and the other mild ointments used in eczema may be employed

alone with greater benefit. An ointment of value is one made up of

from 1 to 2 drams (4.-8.) of liquor carbonis detergens to the ounce (32.)

of simple cerate. Sulphur ointment in the vesicular and vesicobullous

and pustular varieties of the disease, rubbing it in vigorously so as to

break down the lesions, is sometimes serviceable (Duhring, Mackenzie),

but it is a strong application, and must be tried cautiously. Lassar

commends tar baths and tar-and-sulphur ointment as of considerable

curative value.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |